“Our deceased friends are more really with us than when they were apparent to our mortal part.”

By Maria Popova

In the first spring of the nineteenth century, when his patron’s illegitimate son died of a tortuous spinal disease, William Blake (November 28, 1757–August 12, 1827) penned a stirring letter of condolence, included in William Blake vs. the World (public library) — that excellent portrait of Blake’s countercultural courage. On May 2, 1800, Blake — who never ceased grieving his beloved brother Robert and often claimed to see his soul — wrote to William Hayley:

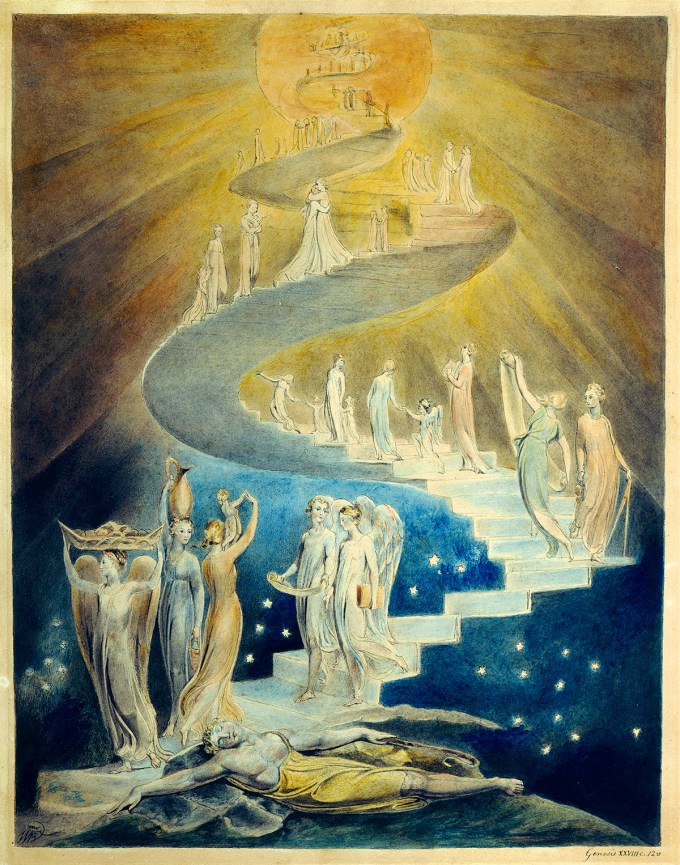

I know that our deceased friends are more really with us than when they were apparent to our mortal part. Thirteen years ago I lost a brother & with his spirit I converse daily & hourly in the Spirit & see him in my remembrance in the regions of my Imagination. I hear his advice & even now write from his Dictate. Forgive me for Expressing to you my Enthusiasm which I wish all to partake of Since it is to me a Source of Immortal Joy: even in this world by it I am the companion of Angels. May you continue to be so more & more & to be more and more persuaded, that every mortal loss is an Immortal Gain. The Ruins of Time builds Mansions in Eternity.

This immortal residue inside the ruin is what Emily Dickinson must have meant as she made her strange insistence that “’tis good — the looking back on Grief” — for the backward gaze brings forth the entire universe that remains of the lost.

Complement with the science of death animated with Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poem “Dirge Without Music,” then revisit the poetic physicist Alan Lightman on what actually happens when we die.

“Each that we lose takes part of us / a crescent still abides, / which like the moon, some turbid night, / is summoned by the tides,” Emily Dickinson wrote as she reckoned with loss after her mother’s death a century and a half before neuroscience illuminated that abiding crescent as a synaptic reality engrained in the brain’s model of the world.

Before O’Rourke, before even Dickinson, another uncommon poet bent his gaze beyond the horizon of his era’s science to arrive at the same elemental truth with his singular gift for harmonizing the material and the mystical.