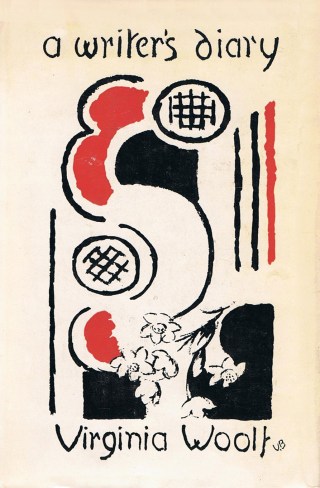

In the springtime of her twenty-ninth year, long before To the Lighthouse and Orlando were but ink drops of thought at the tip of her pen, Virginia writes in her diary:

Nearly a century before her, the young Virginia Woolf (January 25, 1882–March 28, 1941) was yet to wander through her garden and arrive at her flower-fomented epiphany about what it means to be an artist. She was already making a living by her pen, but she was catering rather than creating, writing book reviews and essays for various literary journals — miniatures of her mind, which pulsated with something larger, with its “own creative power restive and uprising,” leaving her raw with self-doubt, the way we always are in those threshold moments before some great leap into our own depths.

Long before Bertrand Russell reflected on how to grow older contentedly, counseling that you must “make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life,” Virginia adds:

I shan’t become a machine, unless a machine for grinding articles. As I write, there rises somewhere in my head that queer and very pleasant sense of something which I want to write; my own point of view. I wonder, though, whether this feeling that I write for half a dozen instead of 1500 will pervert this? — make me eccentric — no, I think not.

These fragments appear in A Writer’s Diary (public library) — the magnificent posthumous volume that gave us Virginia’s reflections on the relationship between loneliness and creativity, what makes love last, the consolations of growing older, the creative benefits of keeping a diary, and her arresting account of a total solar eclipse.

One must face the despicable vanity which is at the root of all this niggling and haggling. I think the only prescription for me is to have a thousand interests — if one is damaged, to be able instantly to let my energy flow into Russian, or Greek, or the press, or the garden, or people, or some activity disconnected with my own writing.

“The most regretful people on earth,” Mary Oliver wrote as she distilled a lifetime of wisdom on creativity, “are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time.”

With an eye to the commercial work syphoning her energy and talent — the era’s equivalent of “content” — she resolves:

Well, you see, I’m a failure as a writer. I’m out of fashion: old: shan’t do any better: have no headpiece: the spring is everywhere: my book out (prematurely) and nipped, a damp firework.

Couple with Keith Haring on self-doubt, then revisit the story of how John Steinbeck used the diary as a tool of creative self-actualization, paving his own way to the Nobel Prize, and Whitman on the discipline of creative self-esteem.