In an era before the Civil Rights movement brought this notion of humanistic brotherhood to the fore of our collective conscience, an era before our language itself could accommodate the notion that this “brother”-hood includes women and instead rendered every woman a “man,” Julia Perry saw how music touches the central mystery of aliveness more deeply and more purely than any of the human labels we impose on life, or on each other, on these miraculous triumphs over night and nothingness that we each are.

The fourth of five daughters to a Kentucky schoolteacher and a pianist-physician, Julia — a cheerful tomboy, fiercely extroverted — was attending a school for gifted children by the age of ten, studying voice and violin, riding her bicycle everywhere, and unspooling her rich dramatic soprano in the town’s chamber music concerts. She was sixteen when her elder sister and musical muse — a gifted pianist and cellist — was killed in a train accident, of which Julia never spoke but which (how could it not) marked her deeply; music (how could it not) became her surviving connection to her sister as it offered its universal salve for grief.

A woman of color and genius in a pre-Civil-Rights white man’s world, she scored the arc of history with her prescient words, doing for the common language of music what Einstein, brilliant and persecuted, had done for the common language of science eight years earlier in the midst of a World War, in the midst of exile.

In 1949, Perry wrote:

She was not yet thirty when her magnum opus, the Stabat Mater, was being widely performed by European and American orchestras. In 1965, her Short Piece for Orchestra became the first composition by a woman of color to be performed by The New York Philharmonic and only the third by any woman. Even after a stroke paralyzed her right hand, Julia Perry taught herself to write with the left so she could go on making music, which she did even at the hospital, composing the last of her twelve symphonies — Symphony No. 12, “Simple Symphony” — there.

Music is an all-embracing, universal language. Music has a unifying effect on the peoples of the world, because they all understand and love it. In music they find common meeting ground. And when they find themselves enjoying and loving the same music, they find themselves loving one another… Music has a great role to play in establishing the brotherhood of man.

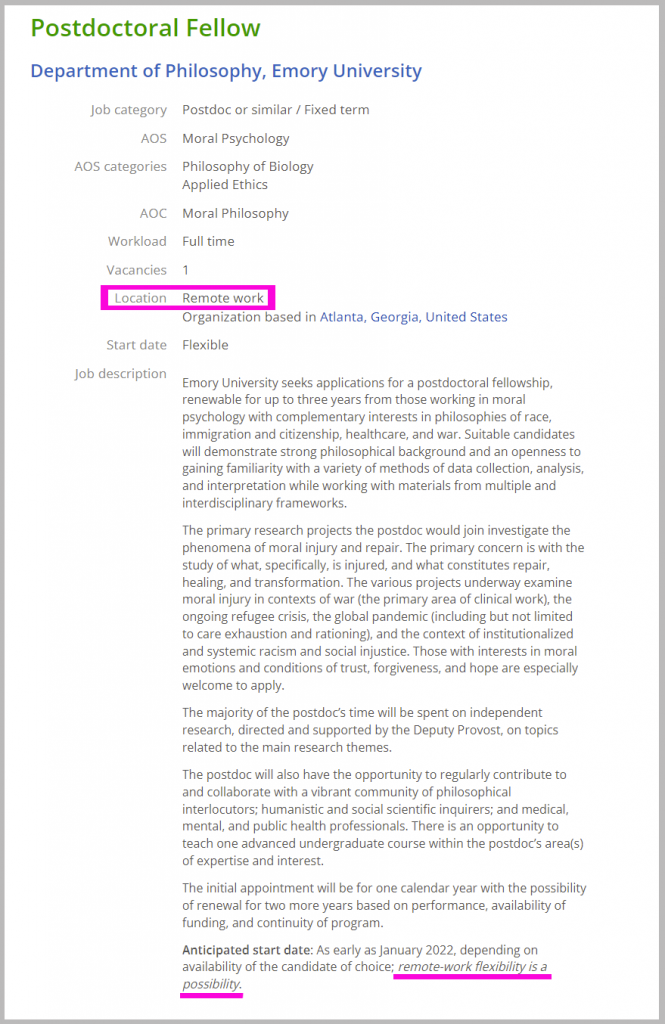

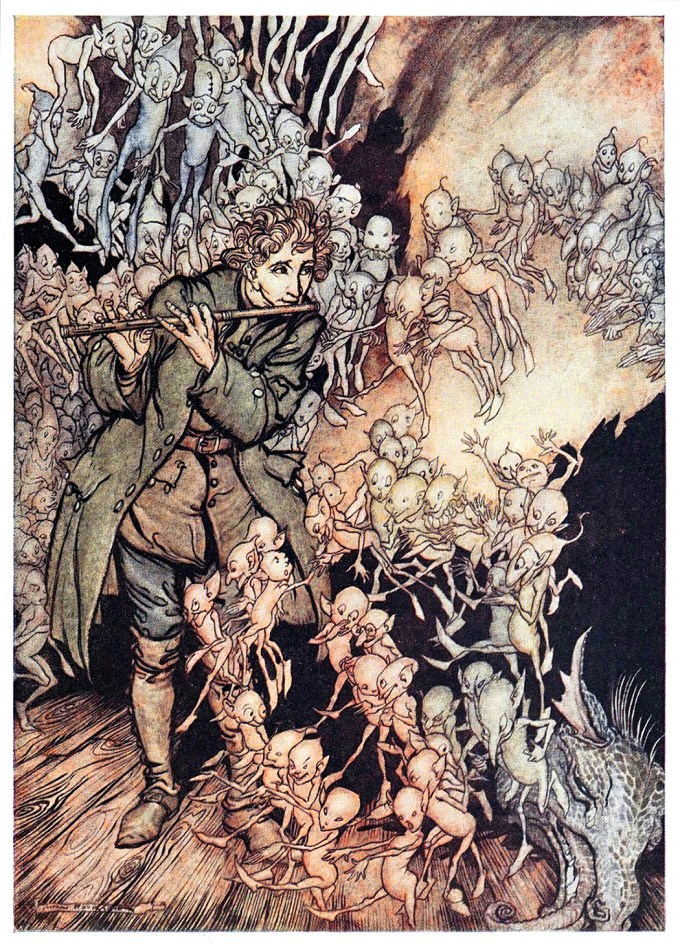

Julia Perry (March 25, 1924–April 25, 1979) studied at Juilliard, studied in Paris, spent more than a decade composing a haunting opera based on the Salem witch trials, wrote an operatic ballet based on Oscar Wilde’s almost unbearably tender book The Selfish Giant and a stunning orchestral requiem for Vivaldi, and went on to fuse the European classical tradition with African spirituals in extraordinary, deeply original music spanning nearly every classical genre, pulsating with an indiscriminate love all that is human, soulful, and therefore beautiful.

Complement with Perry’s German contemporary Joseph Pieper on how music saves our souls, her English contemporary Aldous Huxley on its transcendent power, and her American colleague Aaron Copland (who was also taught by Nadia Boulanger — the first female conductor of The New York Philharmonic, Perry’s teacher in Paris) on how to be a gifted listener, then savor this stunning 2021 performance of Perry’s work by the Experiential Orchestra (who have previously done the same civilizational service — the vital work of resistance to the selective erasure of genius and beauty — for another forgotten, trailblazing composer: the deaf visionary Ethel Smyth).