“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide,” Albert Camus wrote in one of the most provocative opening sentences in all of literature, unspooling into one of the most daring works of philosophy. “Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards.”

And yet live we must, with the cards we have been dealt, daily answering Camus’s question with our pre-answered fundaments of chaos and chance.

Graves grow no green that you can use.

Remember, green’s your color. You are Spring.

By the time we can even begin answering for ourselves the question of whether or not is worth living, myriad things have been answered for us by the fundamental forces that have conspired into the confluence of chance that is our self. None of us choose the bodies or brains or neurochemistries we are born with, the time and place we are deposited into, the parents we are raised by, the culture we are cultured in. Any sense of choice we might have is already saturated with these chance inheritances and is therefore, as James Baldwin so astutely observed, part illusion and part vanity.

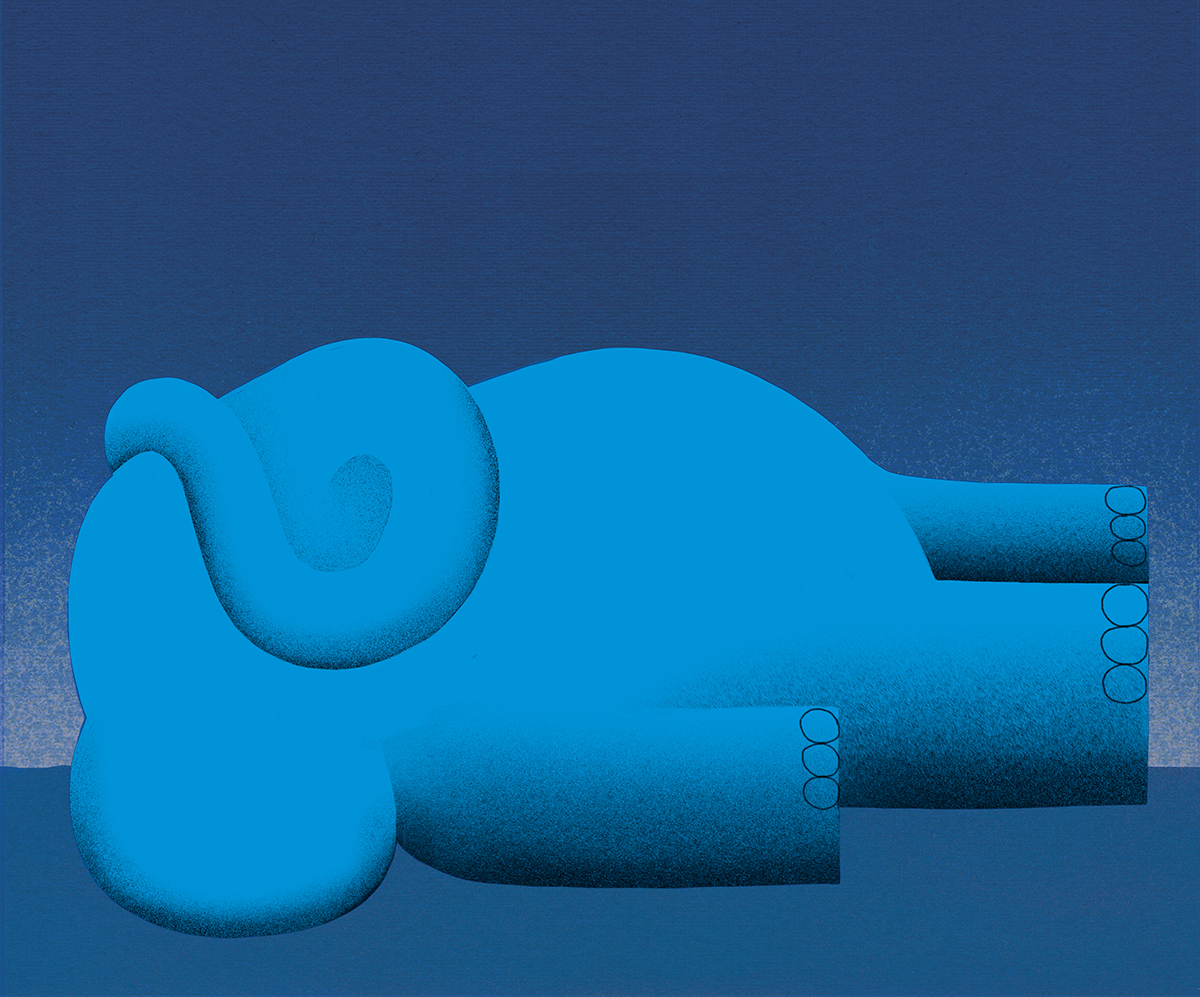

TO THE YOUNG WHO WANT TO DIE

by Gwendolyn Brooks

Sit down. Inhale. Exhale.

The gun will wait. The lake will wait.

The tall gall in the small seductive vial

will wait will wait:

will wait a week: will wait through April.

You do not have to die this certain day.

Death will abide, will pamper your postponement.

I assure you death will wait. Death has

a lot of time. Death can

attend to you tomorrow. Or next week. Death is

just down the street; is most obliging neighbor;

can meet you any moment.

Complement with Galway Kinnell’s kindred poem “Wait,” composed to keep a young friend from taking his own life, then revisit Gwendolyn Brooks on the vivifying power of books and Audre Lorde, in a wonderful anthology edited by Roxane Gay, on poetry as an instrument of change and courage.

She wondered what he must be living through, if so early in life and so early in the day he was already so heavy with despair, so grateful for the salvation of a simple smile from a stranger. (One such smile had saved Little Prince author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s life half a century earlier.)

On those days when we are so life-weary, so defeated by the chance-circumstance of our situation, so tempted to answer in the negative, the smallest gesture of kindness can be nothing less than a lifeline. That is what Gwendolyn Brooks (June 7, 1917–December 3, 2000) realized over breakfast at a hotel one day in her late sixties, when the young waiter met her simple bright “Good morning!” with a gasp on the verge of tears: “Oh, thank you, thank you!”

Out of that compassionate wonderment came Brooks’s lifeline of a poem “To the Young Who Want to Die,” which appeared in her 1987 collection The Near-Johannesburg Boy and Other Poems (public library), dedicated to the students of the Gwendolyn Brooks Junior High School, published by the imprint she had founded and named after her father, the janitor of a music company.

Camus was both very right and very wrong, the way only a great mind can be, because the fundamentals of philosophy come after, not before, the fundamentals of physics.

You need not die today.

Stay here — through pout or pain or peskyness.

Stay here. See what the news is going to be tomorrow.