A quarter century earlier, James Baldwin had captured this in his lovely notion that the artist’s role, the writer’s role, the storyteller’s role is “to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are.”

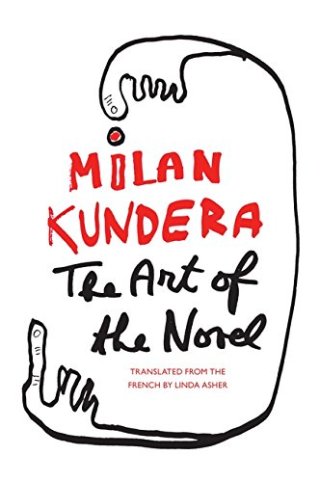

The great Czech-French novelist Milan Kundera articulates this something else with uncommon clarity in The Art of the Novel (public library), published two years after The Unbearable Lightness of Being — the 1984 classic that might be read as one long elegiac entreaty for embracing the uncertainties of love and life, challenging Nietzsche’s notion of “the eternal return.”

Because we are always partly opaque to ourselves even at our most self-aware, fiction and real life have something wonderful in common, wonderful and disorienting: the ability to surprise even the author — of the story or the life.

Kundera locates that suprapersonal wisdom in “the wisdom of uncertainty” — something his poet-compatriot Wisława Szymborska named as the crucible of all creativity in her superb Nobel Prize acceptance speech. In a sentiment evocative of physicist Richard Feynman’s astute observation that uncertainty is the prerequisite for truth and morality, in science as in life, Kundera writes:

In its clinical manifestation, we call this tendency delusion. In its creative manifestation, we call it art — the novel, the story, the poem, the song are each a model, an imagistic impression of the world not as it is but as the maker pictures it to be, inviting us to step into this imaginary world in order to better understand the real, including ourselves.

With an eye to storytellers’ ability to surprise themselves in the telling as the story crosses the terrain of imagined existence under its self-generated momentum, Kundera writes:

A novel examines not reality but existence. And existence is not what has occurred, existence is the realm of human possibilities, everything that man* can become, everything he’s capable of. Novelists draw up the map of existence by discovering this or that human possibility. But… to exist means “being-in-the-world.” Thus both the character and his world must be understood as possibilities… [Novels] thereby make us see what we are, and what we are capable of.

In both, we can set out for one destination and arrive at another, or as another.

In both, we are propelled partly by our directional intentionality and partly by something else, something ineffable yet commanding that draws its momentum from the energy of uncertainty.

Great storytelling, then, deals in the illumination of complexity — sometimes surprising, sometimes disquieting, always enlarging our understanding and self-understanding as we come to see the opaque parts of ourselves from a new angle, in a new light. Kundera writes:

The novel is the imaginary paradise of individuals. It is the territory where no one possesses the truth, neither Anna nor Karenin, but where everyone has the right to be understood, both Anna and Karenin.

Every novel says to the reader, “Things are not as simple as they seem.” That is the novel’s eternal truth, but it grows steadily harder to hear amid the din of easy, quick answers that come faster than the question and block it off.

Complement this portion of Kundera’s altogether illuminating The Art of the Novel with Iris Murdoch on storytelling as resistance, Toni Morrison on storytelling as sacrament to beauty, Susan Sontag storytelling as moral calibration, and Ursula K. Le Guin on storytelling as transformation, then revisit poet Naomi Shihab Nye’s advice on writing, Anton Chekhov’s six rules for a great story, and psychologist Jerome Bruner on the psychology of what makes a great story.

This might be the most transcendent capacity of consciousness, and the most terrifying: that in the world of the mind, we can construct models of the real world built upon theories of exquisite internal consistency; that those theories can have zero external validity when tested against reality; and that we rarely get to test them, or wish to test them. Just ask Ptolemy.

So understood, storytelling becomes a way of walking with uncertainty and sitting with nuance, which is in turn a way of broadening the possibilities of existence in each of our lives. Echoing Adrienne Rich’s notion that all forms of literary imagination are “the arts of the possible,” Kundera writes:

Both are a form of walking through the half-mapped territory of being, real or imagined, making the path in the act of walking and so revising the map with each step.

When Tolstoy sketched the first draft of Anna Karenina, Anna was a most unsympathetic woman, and her tragic end was entirely deserved and justified. The final version of the novel is very different, but I do not believe that Tolstoy had revised his moral ideas in the meantime; I would say, rather, that in the course of writing, he was listening to another voice than that of his personal moral conviction. He was listening to what I would like to call the wisdom of the novel. Every true novelist listens for that suprapersonal wisdom, which explains why great novels are always a little more intelligent than their authors. Novelists who are more intelligent than their books should go into another line of work.