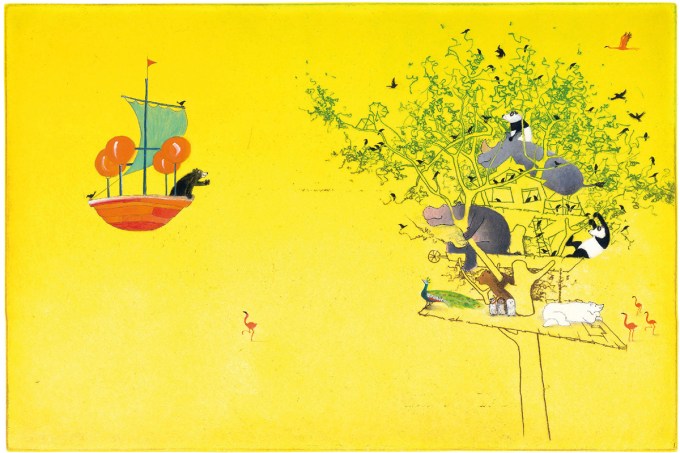

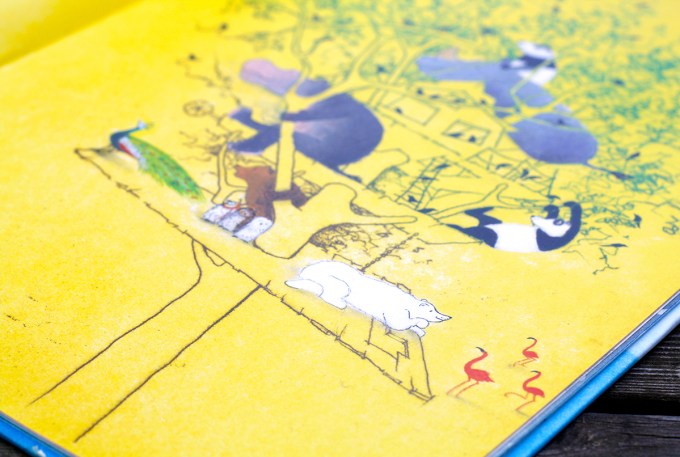

With smiling curiosity about their new home, the two bears explore the treehouse together, then settle into a quiet companionship.

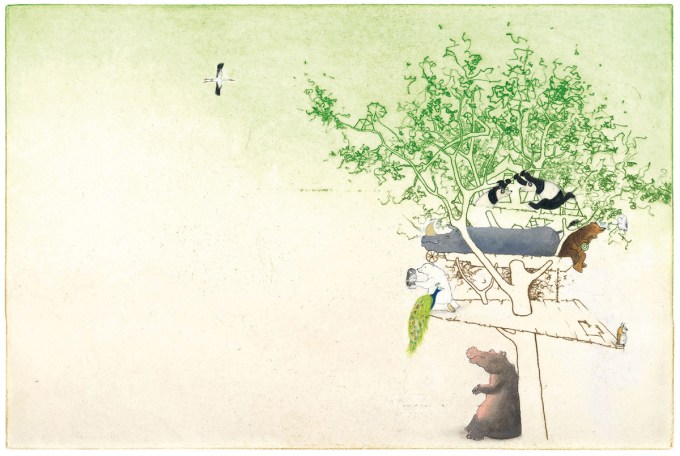

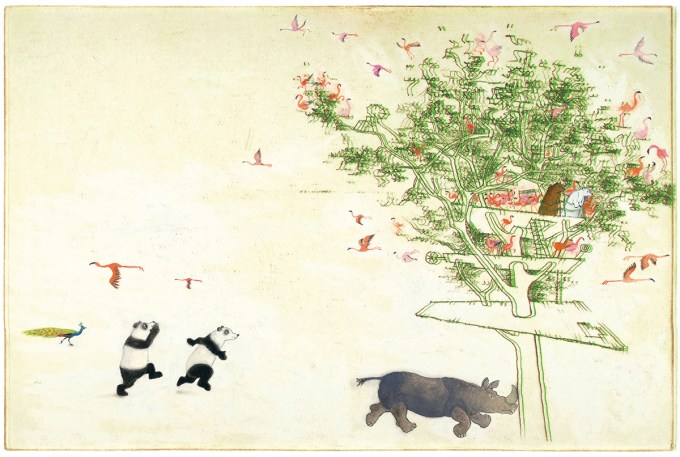

Soon, other creatures follow — the pandas and the peacock and the storks and the hippo. The rhino first rams into the tree trunk, testing the sturdiness of the structure before sprawling contentedly on the treehouse platform as the pandas play in the branches and the polar bear tenderly cradles a baby owl on its paw.

It is a pity that a mere decade after its birth, a book as uncommonly soulful as The Tree House can fall out of print in the world’s most ecologically impactful industrial nation — dead of negligence, dead by the commodification of culture that saturates the atmosphere of our epoch. Perhaps one day, some American publisher of sufficient moral courage and a creative ear for the unscreaming masterpieces of thought and feeling will bring it back from extinction. Meanwhile, a U.K. edition is available online from an independent English publisher and a couple of lovely prints from it are available on Marije Tolman’s website.

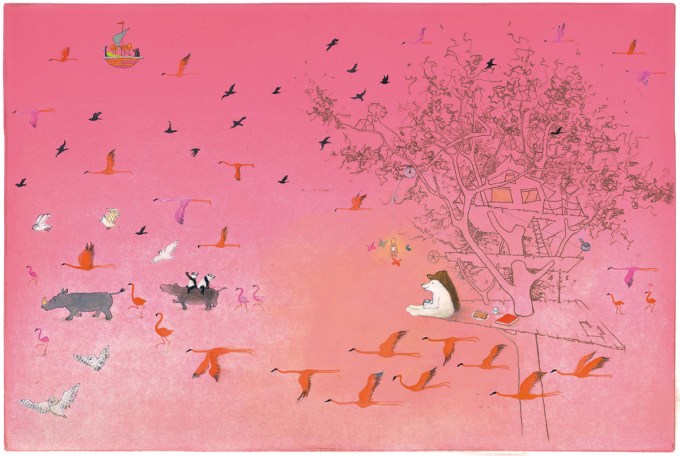

But humans are also the only creatures absent from the story — the treehouse seems like it was built a long time, abandoned, the cracks in it gaping unrepaired.

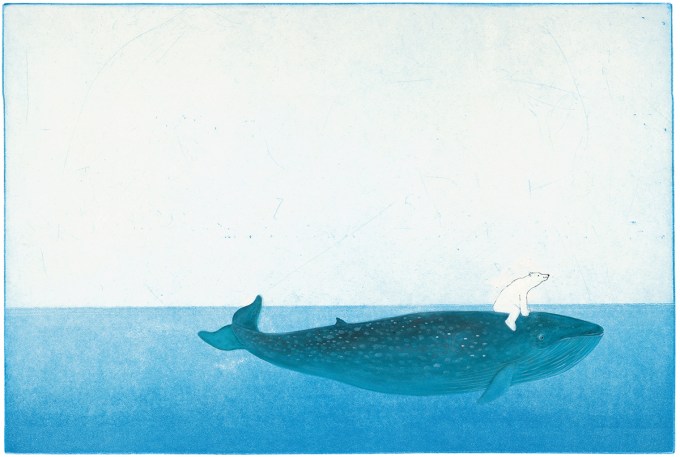

In the warm wordless silence of the story, I read a subtle admonition — unless we make wiser and more generous choices in our regard for the rest of nature, a posthuman future is the only possible future for an ecologically harmonious planet.

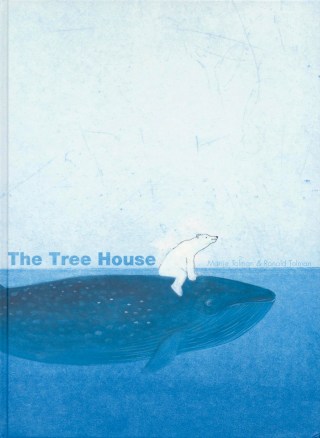

Great picture-books achieve the same thing — which is why Maurice Sendak, perhaps the most poetic picture-book maker of all time, so ardently insisted on musicality as the key to great storytelling. Among the rarest triumphs of the genre is the wordless 2009 masterpiece The Tree House (public library) by Dutch father-daughter artist duo Ronald Tolman, a sculptor, painter, and graphic artist, and Marije Tolman, a graphic designer and children’s book illustrator.

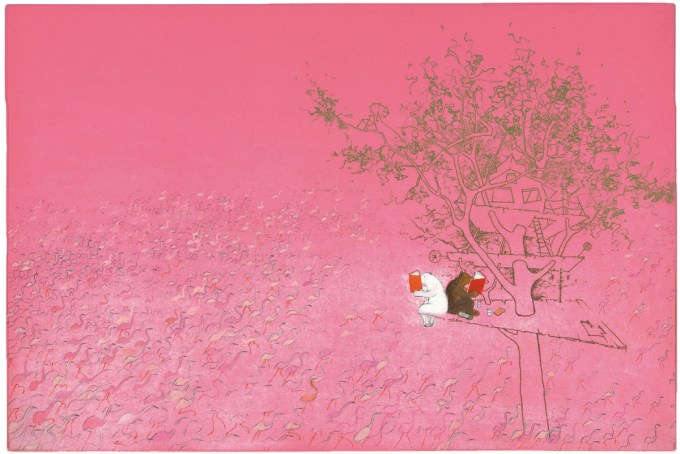

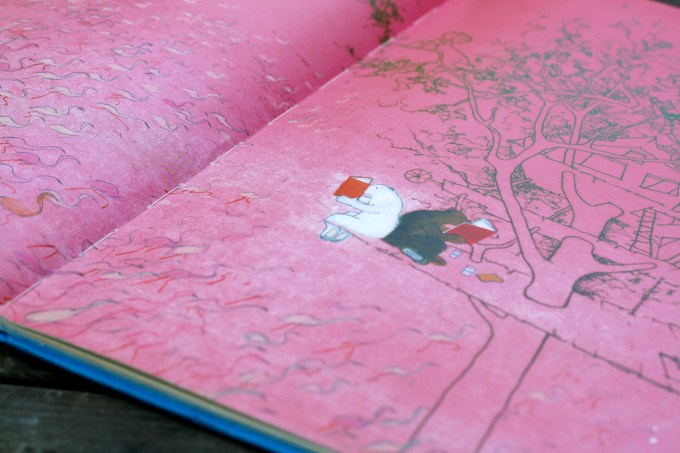

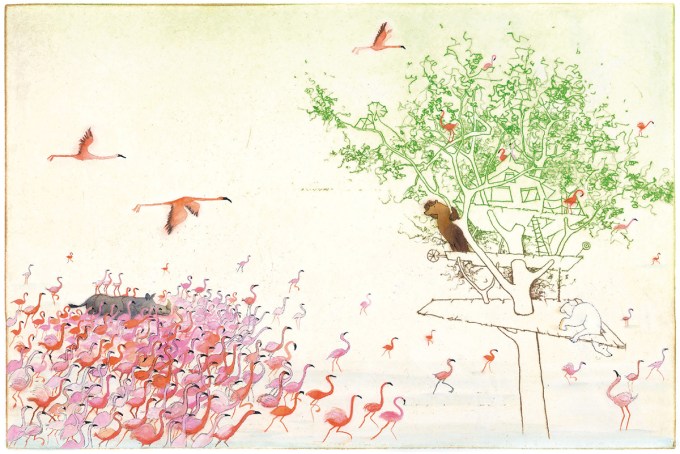

Absorbed in their books, they don’t notice the flamboyance of flamingos rushing toward the treehouse in a tidal wave of pink.

Like a great poem, this pictorial lyric lends itself to multiple conceptual readings. I watch my own interpretation branch off from the other central themes — solitude, camaraderie, loneliness, change — into the ecological: Trees are growing in the melted Arctic and vulnerable creatures are seeking refuge in the ramshackle safehouse of humanity, turning to us who have put them in peril to save them from perishing.

“Words are events, they do things, change things… transform both speaker and hearer… feed energy back and forth and amplify it… feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in her superb meditation on the magic of human communication. But words have limits, for they are the currency of concepts, yet so much of what we try to communicate to one another — so much of our emotional reality — lies in the realm of immediate experience beyond concept. Bach’s Goldberg Variations or a Rothko painting can color our consciousness with a feeling-tone that reaches beyond words to touch us, to transform us, to feed energy back and forth in ineffable ways. At its best, even poetry, though rendered in words, paints images that speak directly to our senses, sings in feeling-tones that harmonize our innermost experience. Poetry, after all, began with music, and music remains the most powerful instrument we have devised for conveying raw emotional reality — something the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay readily and memorably acknowledged when she proclaimed that she would rather die than live without music and exclaimed, “Even poetry, Sweet Patron Muse forgive me the words, is not what music is”; the poetic neurologist Oliver Sacks found echoes of her sentiment in the science, observing music’s “unique power to express inner states or feelings [and] pierce the heart directly.”

It occurs to me that an ecological ethic is itself a matter of filling our creaturely coexistence — which is always bounded by the finitude of our creaturely existence — with enough trust and love to make the precious improbability of life as gladsome as possible for all beings sharing this miraculous island of spacetime.

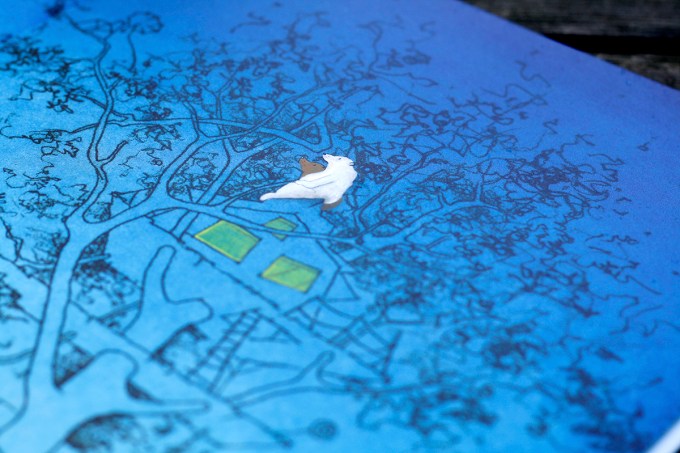

As the bear settles blissfully onto the platform at the foot of the treehouse, it watches another bear, brown and friendly, approach in a boat.

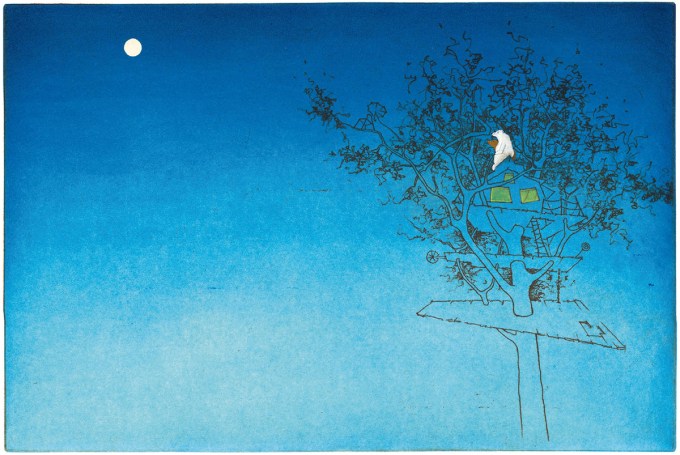

The silent, symphonic story begins with a polar bear swimming gladsomely toward a solitary tree rising from the Arctic waters — a tree already signaling magical realism with its habitational improbability, its magic magnified by the wondrous treehouse poking through its branches.

On the final spread, with all the other creatures vanished — back to their homes, or back to the stardust of nonsurvival — the two bears are left sitting side by side atop the empty treehouse, staring solemnly at the Moon, radiating the tender ecological counterpart to that wonderful line from artist Louise Bourgeois’s diary: “You are born alone. You die alone. The value of the space in between is trust and love.”