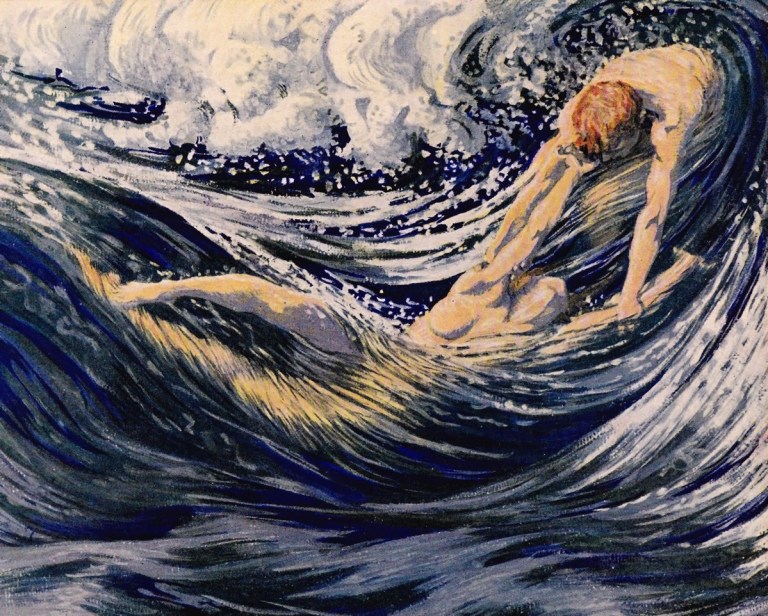

There is violence in this: the body breaking the glassy surface, crashing through it, the blasting noise in one’s ears — and the feeling on one’s skin, of one’s skin and nerves, down to the bones. It is a sensation not unlike pain.

I suppose it is pain. I think of icicles breaking. There is sharpness. I have my goggles on and see what I feel: chaos, a watery chaos, a chaos of sensations. Murky greens and browns and blacks and also splashes of white, like slashes of paint, through the transparency, through the vitreous of the eye of the lake. I see my arms akimbo before me, and bubbles — air bubbles. I feel like a scuba diver with no gear, and there is a flash of panic; the water is cold, fifty degrees I’m told, and I am almost confused by it, the not-rightness of it. But in that same instant, I am moving forward, pushing through the water, onward.

I see the green transparency lightening, the surface nearing. I reach my right hand forward as far as I can and my left arm back, as if pulling the string on a bow, in position to launch into freestyle as soon as I emerge.

Surfacing is the opposite of plunging, but it feels the same, the huge chaos of sensations — sensations of temperature, water, force, light. Yes, now there is light as I break through and see the shore, the boathouse, trees, and I grab for air (that’s how it feels, gasp is not the right word, it has a physical, muscular feeling to it), grab a lungful, and thrust, pull, kick, rotate: swim. I go as far as four or five breaths will take me, as far as I can go without thinking of anything else, then turn around. Climbing onto the dock, my skin and muscles are taut, oxygenated.

That interpenetration of the elemental and the existential what Bill Hayes explores in the lovely opening pages of Sweat: A History of Exercise (public library).

This ablution is no small gift to our civilization-stifled lives, in which the body is an afterthought of the mind and the ego. But beneath it is something more primal than mere pleasure — we are each formed, after all, in the portable ocean of the womb, having begun our collective evolution in the immense womb of Earth’s primordial ocean. As we swim, we are not so much forgetting civilization as remembering our elemental nature. It is hardly surprising that swimming figures into some of our deepest sensemaking — Kafka drew on it in exploring the nature of reality and Alan Watts wove it into his summation of a basic tenet of Taoism.

“Because I can,” I say.

Complement with artist Lisa Congdon’s illustrated love letter to swimming, then revisit Bill Hayes on the scientific poetics of sleep, with a salve for insomnia from Maurice Sendak.

He begins his magnificent chronicle of working out the body and the soul where we all have always begun: with swimming — something he grew up doing with his father, onetime captain of the West Point swim team, and then rediscovered half a century later with his late partner, the irreplaceable Oliver Sacks, a devoted swimmer himself.

As he details the physiology of the experience, the native poetry of the body emerges:

Later, a friend asks me why I would do this — it’s October, for God’s sake; the lake is freezing.

I kick hard, instinctively feeling that by kicking I will get away from the cold. There is nothing else to do. Now I see my arms stretched out before me, my hands in a V, and I am bulleting through the water, conscious that I am moving — flying — and that the air in my lungs is running out.

Describing the strange thrill of plunging into a mountain lake at the peak of autumn, he writes:

“As you swim,” Anaïs Nin wrote in her soulful meditation on summer and the art of presence, “you are washed of all the excrescences of so-called civilization, which includes the incapacity to be happy under any circumstances.”