[…]

[…]

She learns what we all do once some cataclysm awakens us to the finitude and fragility of life — that this appetite for life is best roused by the most prayerful of acts: the act of paying attention; that to see the world more clearly is to love it more deeply.

The detour, of course, became the actual path; the digressions in my writing, the narrative… As with all major detours, all lessons of impermanence, what might have been a straight shot is full of bumps and bends.

Ehrlich writes in the preface:

She writes:

And yet this cosmic perspective, this sublime invitation to unselfing (to borrow once again Iris Murdoch’s splendid notion), is readily available everywhere we look, right here on Earth, so long as we are actually looking. A century after Hermann Hesse observed that “whoever has learned how to listen to trees… wants to be nothing except what he is,”, Ehrlich writes:

And yet this cosmic perspective, this sublime invitation to unselfing (to borrow once again Iris Murdoch’s splendid notion), is readily available everywhere we look, right here on Earth, so long as we are actually looking. A century after Hermann Hesse observed that “whoever has learned how to listen to trees… wants to be nothing except what he is,”, Ehrlich writes:

Looking back on the experience and the otherworldly world into which it took her, she reflects on what it taught her about life and the life-reckoning we call art — which, of course, is the only value of experience:

There is nothing in nature that can’t be taken as a sign of both mortality and invigoration… Everything in nature invites us constantly to be what we are.

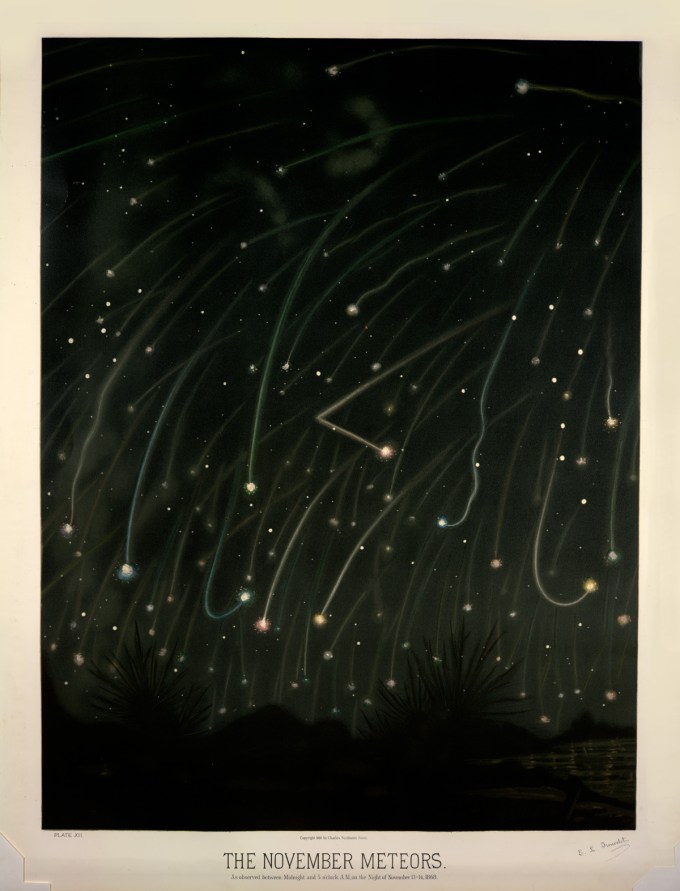

Last night from one in the morning until four, I sat in the bed of my pickup with a friend and watched meteor showers hot dance over our heads in sprays of little suns that looked like white orchids. With so many stars falling around us I wondered if daylight would come. We forget that our sun is only a star destined to someday burn out. The time scale of its transience so far exceeds our human one that our unconditional dependence on its life-giving properties feels oddly like an indiscretion about which we’d rather forget.

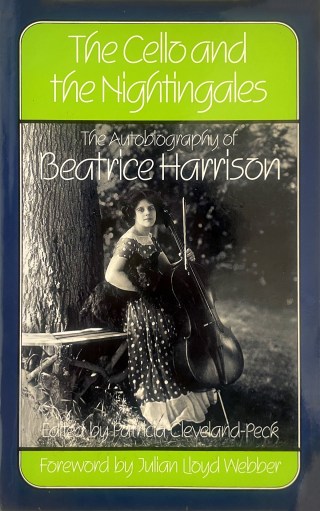

What it means and what it takes to be more attentive and alive is what Gretel Ehrlich explores in her classic essay collection The Solace of Open Spaces (public library) — a living affirmation of Emily Dickinson’s pronouncement that “‘Tis good — the looking back on Grief,” written in the years following a devastating loss that had dislodged Ehrlich from orbit and sent her a thousand miles from home, into the arid heart of the landmass. There — in the savage desert of grief, amid the austere hundred-mile views of Wyoming and the rugged kindness of its people — she discovers canyons that “curve down like galaxies to meet the oncoming rush of flat land” and a new kind of toughness that is “not a martyred doggedness, a dumb heroism, but the art of accommodation”; she discovers what she is made of: something transient yet tenacious, not dismantled by loss but recomposed by it.

We live amid and inside emblems of the touching longing for permanence that both defines us and defies reality: our houses, these haikus of brick and hope so easily discomposed by a tremor of the earth or a tempest of the sky; our homes, so easily hollowed by death or indifference; our bodies, these boarding houses for stardust. All along, as life keeps living itself through us, we keep casting ourselves in the role of living it — that is what makes all the uncertainty bearable. But deep down in the animal marrow of being, we know that it will end, and that no wall or wish can make it otherwise, and that the only measure of our aliveness — the only redemption of our mortality — is how attentive and awake we are to the savage beauty that fills the interlude between nothingness and nothingness.