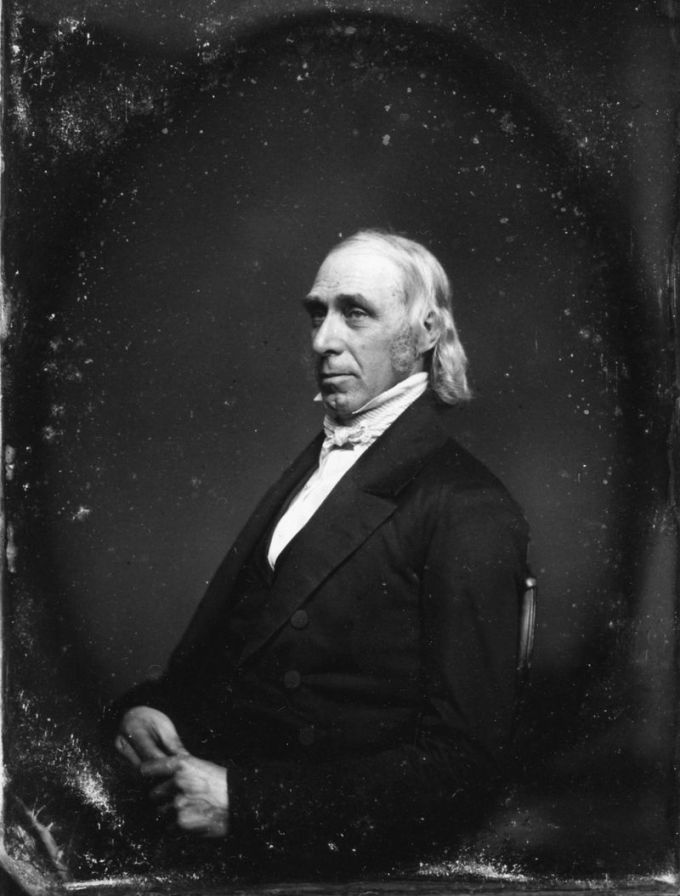

The progressive philosopher, abolitionist, education reformer, and women’s rights advocate Bronson Alcott (November 29, 1799–March 4, 1888) developed his ideas about human flourishing and social harmony by observing and reflecting on the processes, phenomena, and pleasures of the natural world — something he shared with the Transcendentalists of his generation, and particularly with his best friend: the naturalistic transcendence-shaman Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1856, while living next door to the visionary Elizabeth Peabody in Boston — the seedbed of Transcendentalism, a term Peabody herself had coined — Alcott borrowed and devoured Emerson’s copy of a book sent to him by an obscure young Brooklyn poet as a token of gratitude for having inspired it: Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, published months earlier.

Complement with Derek Jarman on gardening as creative redemption and training ground for presence, then revisit Whitman, writing while recovering from a paralytic stroke in the nursery of nature, on what makes life worth living.

“I had a pleasant time with my mind, for it was happy,” Louisa May Alcott wrote in her diary just after she turned eleven, a quarter century before Little Women bloomed from that uncommon mind — a mind whose pleasures and powers were nurtured by the profound love of nature her father wove into the philosophical and scientific education he gave his four daughters.

By mid-summer, Alcott had discovered in his garden not only a creaturely gladness but a portal into the deepest existential contentment — something akin to the creative intoxication that he, like all artists, found in his literary calling:

Whitman’s unexampled verse — so free from the Puritanical conventions of poetry, so lush with a love of life, so unabashedly reverent of nature as the only divinity — stirred a deep resonance with Bronson’s own worldview and inspired him to try his hand at the portable poetics of nature: gardening.

My garden has been my pleasure, and a daily recreation since the spring opened for planting… Every plant one tends he falls in love with, and gets the glad response for all his attentions and pains. Books, persons even, are for the time set aside — studies and the pen. — Only persons of perennial genius attract or recreate as the plants, and of books we may say the same, as of the magic of solitude.

Human life is a very simple matter. Breath, bread, health, a hearthstone, a fountain, fruits, a few garden seeds and room to plant them in, a wife and children, a friend or two of either sex, conversation, neighbours, and a task life-long given from within — these are contentment and a great estate. On these gifts follow all others, all graces dance attendance, all beauties, beatitudes, mortals can desire and know.

Right there in the middle of bustling Boston, where his young country was just beginning to find its intellectual and artistic voice, Alcott set up his humble urban garden. One May morning — a century and a half before bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer contemplated gardening and the secret of happiness, before Olivia Laing wrote of gardening as an act of resistance, before neurologist Oliver Sacks drew on forty years of medical practice to attest to the healing power of gardens — the fifty-six-year-old Alcott planted some peas, corn, cucumbers, and melons, then wrote in his journal: