It is here that we find the strongest expression of Blake’s politics. True politics are not ideologies to discuss, but an attitude to your relationship with the world which is enacted in your daily life. Your politics are not what you tell yourself you believe. They are not the set of ideas that you identify with, or look to for personal validation of your goodness as a human being. Your politics are expressed in the choices that you make, the way you treat other people, and the actions you perform. It is here that hypocrisy and vanity fall away, as the reality of your politics is revealed in the countless decisions that you make every day. Who you work for, whether you volunteer for charity work, if you become a landlord, whether you eat meat, the extent to which you pursue money and consumer goods — these are the types of decisions in which our true politics are expressed… Blake needed commercial engraving work to keep a roof over his head. But he also needed to be free of compromise when it came to his own work. He produced his art as an individualist antinomian, asking no permission, answering to nobody.

Those who knew William Blake (November 28, 1757–August 12, 1827) cherished his overwhelming kindness, his capacity for delight even during his frequent and fathomless depressions, his “expression of great sweetness, but bordering on weakness — except when his features are animated by expression, and then he has an air of inspiration about him.” He was remembered for the strange, koan-like things he said about Jesus (He is the only God. And so am I and so are you.), about the prosperous artists who held his poverty as proof of his failure (I possess my visions and peace. They have bartered their birthright for a mess of pottage.), about the nature of creativity (The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing which stands in the way… As a man is, so he sees.)

Blake himself put it both beautifully and bluntly:

Higgs writes:

Centuries before zines, before blogs, before Instagram, before Substack, William Blake had built himself an autonomous platform on which to share his creative labors, exactly as he wanted them to live.

So he learned mirror-writing.

As an artist, he was resolutely his own standard, his own guiding sun. Like Beethoven, with whom he shared a death-year and the stubborn unwillingness to compromise on the artistic vision he experienced as life, Blake was determined to make what he wanted to make and to make it on his own terms — in a world unready for the art and unfriendly to the terms.

No such technique existed.

There cannot be more than two or three great Painters or Poets in any Age or Country; and these, in a corrupt state of Society, are easily excluded, but not so easily obstructed.

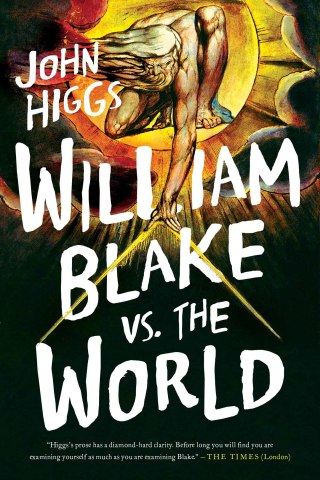

In William Blake vs. the World (public library) — the best book on Blake in the seven decades since Alfred Kazin’s masterpiece — John Higgs captures just how radical this was, both as a technology of creation and as an ethos:

So he invented it.

The Labours of the Artist, the Poet, the Musician, have been proverbially attended by poverty and obscurity; this was never the fault of the Public, but was owing to a neglect of means to propagate such works as have wholly absorbed the Man of Genius. Even Milton and Shakespeare could not publish their own works.

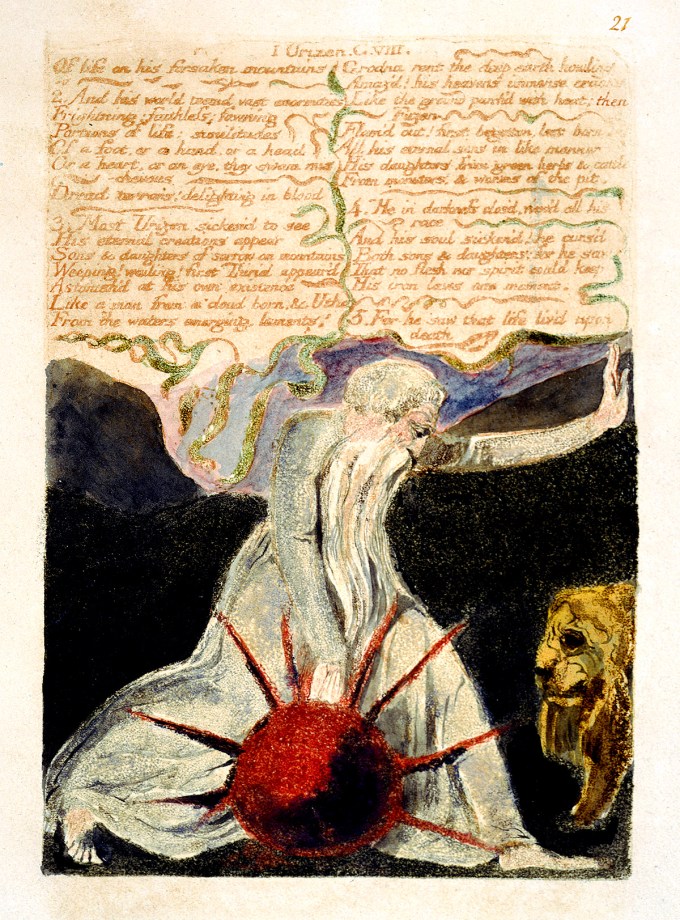

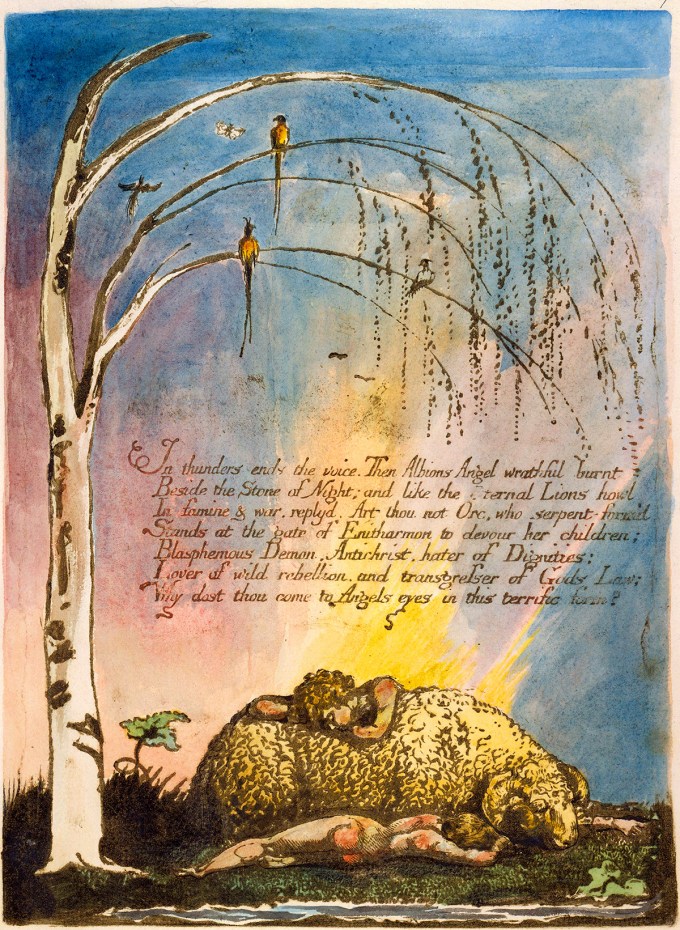

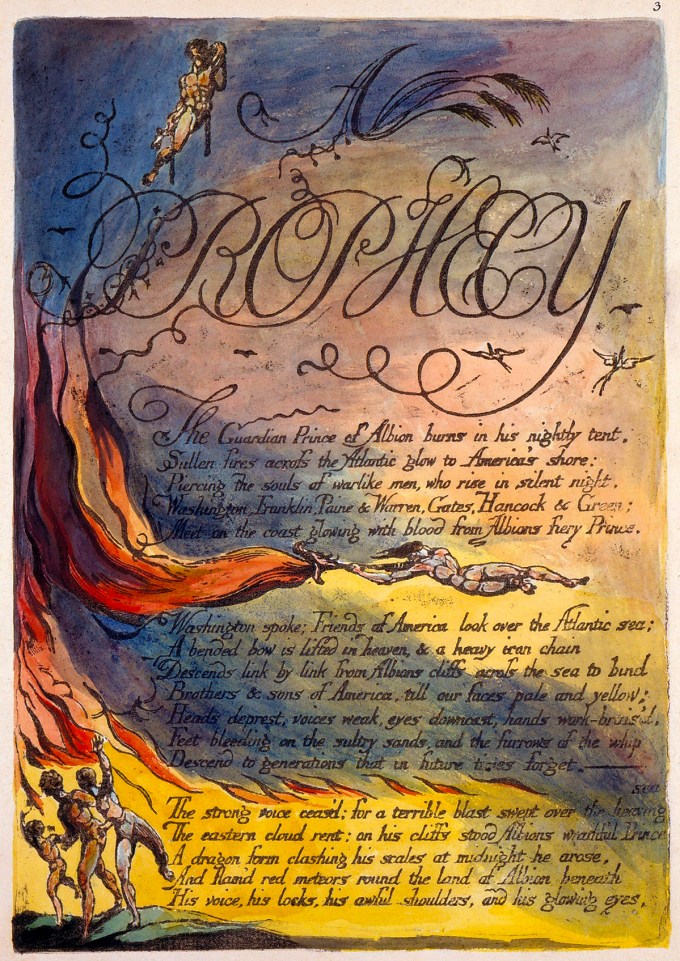

Eighteenth-century printing was a complex job which involved many specialist tradesmen. One person wrote the book, another was responsible for editing it, and a third typeset the text. An artist designed illustrations for an engraver to produce, and a printer put each page through the press, once for text and a second time for the images. On occasions, these would be hand-coloured by another specialist, and finally a bookseller would sell the finished book. Thanks to Blake’s new technique, he had the ability to do all these tasks himself. He was a one-person publishing industry, writing, designing, printing and colouring illustrated works of his own devising. Although he was still in the Georgian era, Blake was practising the “do it yourself” ethos of punk rock.

Unseen by his own world, he saw deep into the worlds to come, channeling his visions through anything at hand. It was not the medium that mattered, but its pliancy as he bent it to his vision of the mystery that is itself the message — the message we call art: He was a painter, a poet, a philosopher without meaning to, an early prophet of panpsychism, a mystic who lived not to solve the mystery but to revel in it, to encode it in verses and etch it onto copper plates and stain it onto canvases and seed it into souls for centuries to come.

Suddenly, William Blake had unfettered himself from the production machine, giving his creative might free rein. His new process, he estimated, enabled him to make what he wanted to make for a quarter of the cost. He was a one-man operation, creating in his own space and with his own hands what ordinarily took entire teams of artisans and craftsmen, each with different training, using different tools, working in different workshops.

For an uncompromising counterpart in music, revisit the story of how Beethoven made his “Ode to Joy,” then savor Esperanza Spalding’s soulful strings-and-voice rendition of Blake’s short existentialist poem “The Fly” and this lovely vintage picture-book celebrating his uncommon legacy.

In the first days of a bleak London December in 1827, a small group of mourners gathered on a hill in the fields just north of the city limits at Bunhill Fields, named for “bone hill,” longtime burial ground for the disgraceful dead. There, in what was now a dissenters’ cemetery, the English Poor Laws had ensured a pauper’s funeral for the man who had died five days earlier in his squalid home and was now being lowered into an unmarked grave. The man whose “Songs of Innocence” would light the creative spark in the young Maurice Sendak’s imagination a century-some later. The man Patti Smith would celebrate as “the loom’s loom, spinning the fiber of revelation” — a guiding sun in the human cosmos of creativity.

There is no greater act of creative courage than this.

The magnitude of his innovation was not lost on Blake. In 1793, he composed and printed his Prospectus, addressed “TO THE PUBLIC,” in which he announced that he had “invented a method of Printing both Letter-press and Engraving in a style more ornamental, uniform, and grand, than any before discovered.” It was nothing less than a manifesto for creative self-liberation:

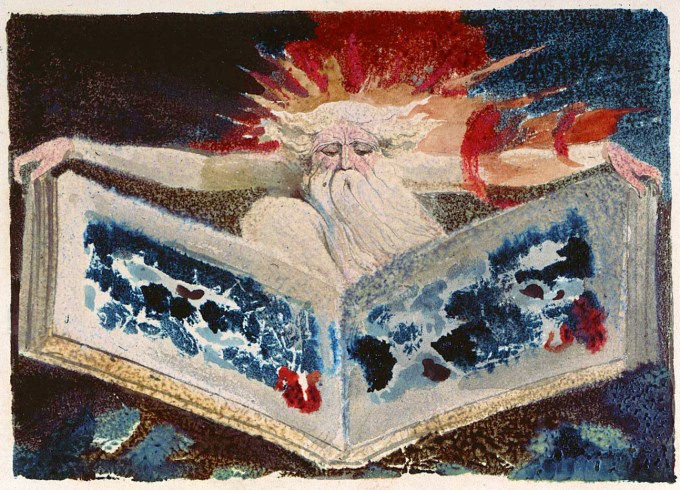

All the while, Blake’s mind bustled and bloomed with the transcendent chaos of his own ideas. He pressed the plates onto white paper, watching the ink held in the tiny canals of the etchings render stark yet delicate black-and-white shapes, alive with light and shadow.

Precisely because he was his own standard, because he wanted to make exactly what he wanted to make, it was enough for him that a handful of devoted fans became his collectors and commissioned work he was inspired to make. It was just about enough to live on. And it was never what he lived for. (Centuries later, this ethos — which I believe is the natural state of the creative spirit — still raises eyebrows as radicalism.)

There was only one challenge with his invention: Because the print was still made by pressing a plate onto a page, any text he painted onto the plate was printed backward.

It was beautiful, but it was intensely toilsome — he could barely make a living illustrating other people’s work, and it left no time for his own art. He yearned for a different technique that could achieve the same result in less time and with less toil.

Blake’s politics… existed in what he created. He may have had great empathy with the poor, but he did not spend his days working to better their situation. Instead, he believed that the imagination was the tool needed to improve society, and… would do more to liberate people than canvassing or protesting. To do this would take integrity, self-belief, and effort.

Rather than cut the shapes onto the plates with his sharp steel burin, he painted directly onto the copper with a quill or brush dipped in acid-resistant varnish, then bathed the plates in acid, which stripped a layer of the surface to revealed the embossed shape of what he had drawn. A complaint made in chemistry and creative restlessness.

Poverty is no friend to the creative spirit, nor to this artist who knew that “Man has no body distinct from his Soul for that called Body is a portion of Soul.” To feed the body, Blake worked long wearying hours as an engraver for hire, squinting at sheets of copper to scratch and cross-hatch shapes onto them in intricate patterns of dots and lines. “Engraving is Eternal work,” he sighed to a client who grumbled that a project was taking too long.

And so, centuries before the technologies existed to enable the proof, William Blake became the first living conjecture of the 1,000 True Fans theory. He knew what we all eventually realize, if we are awake and courageous enough: that the best way — and the only effective way — to complain about the way things are is to make new and better things, untested and unexampled things, things that spring from the gravity of creative conviction and drag the status quo like a tide toward some new horizon.

Here is where a cynic or a Silicon Valley entrepreneur might scoff, So what? He died a pauper. And here is where Blake would wince back, as he did in a letter, I should be sorry if I had any earthly fame, for whatever natural glory a man has is so much detracted from his spiritual glory.

[…]

It came to him, he said, as a message from his dead brother’s spirit.

If a method of Printing which combines the Painter and the Poet is a phenomenon worthy of public attention, provided that it exceeds in elegance all former methods, the Author is sure of his reward.

The new technique gave Blake full creative freedom and full control of production. Suddenly, he could combine text and image on a single page, in a single process, which neither traditional engraving nor etching could do — both required separate space for lettering and a second production pass for type-setting the words.

In the very act of this choice, he was modeling a kind of moral beauty that reached beyond art, into life itself — an unwillingness to accept the limitations imposed upon any present by the momentum of its past, a winged willingness to do whatever it takes to transcend them, which begins with a new way of seeing: seeing the limitations and seeing the alternate possibilities. For the Eye altering alters all.