Gebser, who swam in Jung’s circles and drank at Rilke’s fount, realized that for us creatures of time, creatures whose very consciousness is woven of temporality, an altered relationship with time is an altered relationship with ourselves — inner upheaval so profound on the scale of the individual, and so total on the scale of the species, that every major upheaval in the outer world can be traced to it when followed back closely and lucidly enough. To live more harmoniously with ourselves and each other, Gebser concluded, demands nothing less than a recalibration of our relationship with time itself.

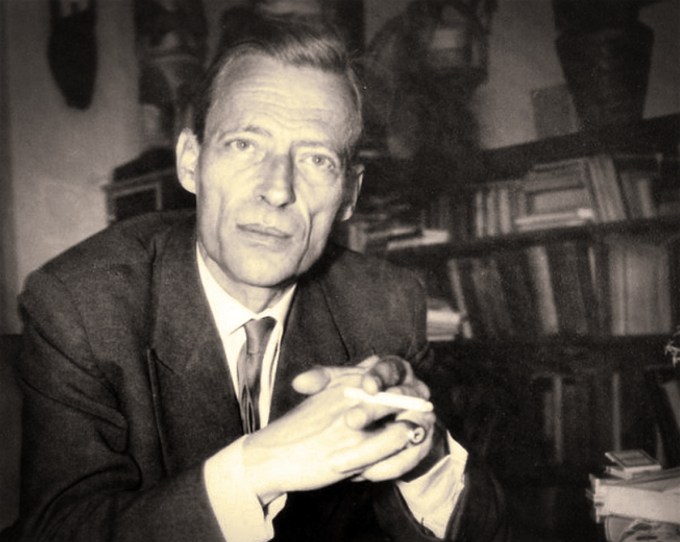

In 1932, when Le Guin was only just beginning her being, when humanity was still reeling from its first global war and seething with the forces about to stir the second, the Swiss poet, philosopher, and linguist Jean Gebser (August 20, 1905–May 14, 1973) saw, in what he later described as a “lightning-like flash of inspiration,” the elemental disruption of the human spirit pulsating beneath the savage tumults of the surface: our altered relationship with time — a transformation catalyzed by the Galilean dawn of timekeeping in the sixteenth century, accelerated by the invention of motion photography in the nineteenth, and exploded by the birth of relativity in the twentieth.

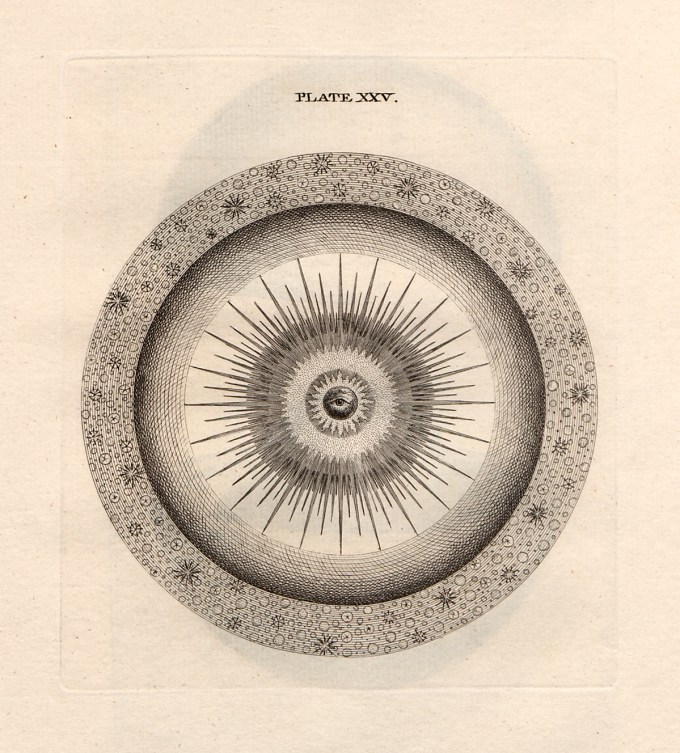

As the origin before all time is the entirety of the very beginning, so too is the present the entirety of everything temporal and time-bound, including the effectual reality of all time phases: yesterday, today, tomorrow, and even the pre-temporal and timeless.

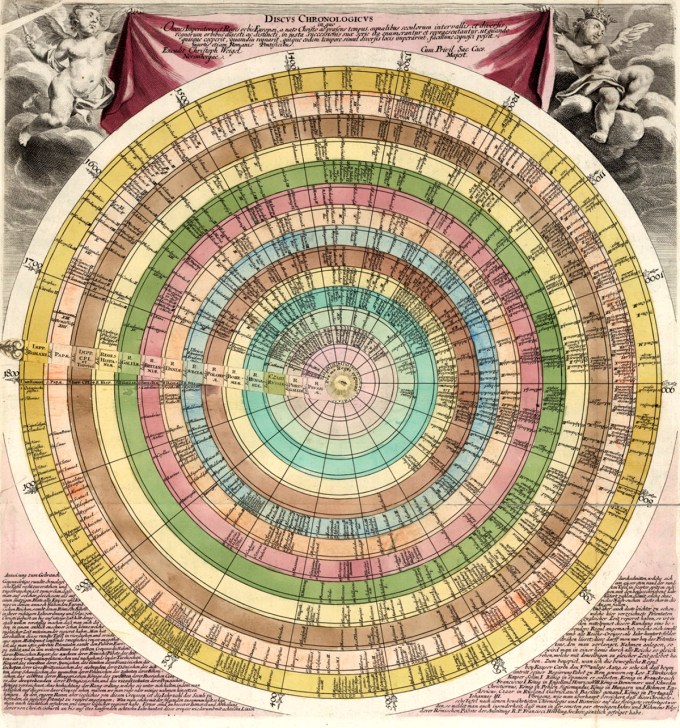

With an eye to how the Renaissance discovery of perspective in art and architecture radicalized our relationship to space, thus revolutionizing our consciousness itself, Gebser argues that a similar transformation needs to take place in our relationship to time — a shift from the “unperspectival” past to a properly perspectival present that opens the portal to an “aperspectival” future, something beyond perspective, implying a fully integrated and interconnected consciousness indivisible into separate perspectives — the ultimate way of achieving perspective,” we might say. In a sentiment of staggering prescience nearly a century later — which is also a touching testament to our being a perennial work in progress that continually mistakes itself for near-complete — he writes:

At a time when mankind is suffering… from scepticism and suspicion or… from ideological anxiety, anyone audacious enough to recall some basic values that run counter to the superficial course of events and seem to lack any immediate “efficiency” in a world given over to quantification is all too readily dismissed as being, in the familiar clichés, “unrealistic” and “idealistic.” These are perhaps the most innocuous of the terms used by those who confuse realism with material utility and thus fall prey to a dualistic fallacy even where it has nothing to do with idealism. As a type, they lack perception of those powers of which realism and idealism are only conceptual and classifying aspects. In addition there is the obstinacy resisting change which emerges even where it is obvious that it is unable to resolve an intractable problem. A person for whom the present, even during his or her finest hours, is no more than a time-bound moment, will not participate in the emerging transformation. Only those will succeed for whom the present becomes a time-free origin, a perpetual plenitude and source of life and spirit from which all decisive constellations and formations are completed.

A short verse from “Das Wintergedicht” — the long 1944 “Winter Poem” through which Gebser first gave shape to the ideas that became The Ever-Present Origin, composed in a single forty-five-minute burst of creative force — captures the heart of his timeless and atemporal insight into the urgency of being:

In the postscript to the book, penned in the early 1950s amid a world scarred by two World Wars and newly petrified with the terror of the Cold War, Gebser calls out to the highest and most courageous part of us, the part even more assaulted by the mass cowardice of cynicism in our own time, amid the transitional world we live in, the world Gebser presaged:

A new consciousness and a new reality, Gebser cautions, can only arise from a more intimate and examined knowledge of the past and its pitfalls — “a consciousness of the whole, an integral consciousness encompassing all time and embracing both man’s* distant past and his approaching future as a living present,” which is not an intellectual but a spiritual orientation to time. In a lovely antidote to the diffusion of responsibility that marks our social species — and that, in its most urgent present manifestation, has landed us in our climate catastrophe — he roots us back into the tiny, infinite locus of our personal potentiality:

Before we can discern the new, we must know the old.

These inceptions were all anticipations, the seedlings as it were, of later blossoms that could not flourish with visible and immediate effect in their respective ages, since they were denied receptive soil and sustenance.

To ward off the menace, Gebser cautions, we need to find this “new factor,” to seize it for all it is worth and wrest from it the transformation — which he calls a “mutation” of consciousness — necessary for ensuring our continuance as a planetary species.

“Time is being and being time, it is all one thing, the shining, the seeing, the dark abounding,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in her splendid “Hymn to Time” shortly before she returned her borrowed being to eternity.

Complement with physicist Alan Lightman’s poetic meditation on time and the antidote to our existential anxiety, then revisit the nineteenth-century psychiatrist and mountaineer Maurice Bucke’s pioneering theory of cosmic consciousness, formulated half a century before Gebser, and cosmologist Stephon Alexander, writing a century after him, on dreams, consciousness, and the nature of the universe.

In a sentiment Bertrand Russell would echo two years later in the seventh of his ten commandments of critical thinking for a more possible future — “Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.” — Gebser adds:

We have only one option: in examining the manifestations of our age, we must penetrate them with sufficient breadth and depth that we do not come under their demonic and destructive spell. We must not focus our view merely on these phenomena, but rather on the humus of the decaying world beneath, where the seedlings of the future are growing, immeasurable in their potential and vigor. Since our insight into the energies pressing toward development aids their unfolding, the seedlings and inceptive beginnings must be made visible and comprehensible.

If our consciousness, that is, the individual person’s awareness, vigilance, and clarity of vision, cannot master the new reality and make possible its realization, then the prophets of doom will have been correct. Other alternatives are an illusion; consequently, great demands are placed on us, and each one of us have been given a grave responsibility, not merely to survey but to actually traverse the path opening before us.

Gebser argues that it is only by rendering transparent “the concealed and latent aspects” of our dawning future, in those vital periods of transition, that we come to fully “clarify our own experiencing of the present.” Affirming humanistic contemporary Erich Fromm’s insistence on the need to move beyond the simplistic divide of optimism and pessimism, Gebser calls for “overcoming the mere antithesis of affirmation and negation” as essential to this evolution in consciousness by which we can attain the new reality — “a reality functioning and effectual integrally, in which intensity and action, the effective and the effect co-exist; one where origin… blossoms forth anew; and one in which the present is all-encompassing and entire.”

In a sentiment evocative of the Buddhist nun and teacher Pema Chödrön’s insight that “only to the extent that we expose ourselves over and over to annihilation can that which is indestructible be found in us,” he writes:

In the remainder of The Ever-Present Origin, Gebser goes on to explore the three consciousness structures that have marked the history of our species — the magic, the mystical, and the mental: all springing from origin, but each successive one increasing the intensity of consciousness. Dismantling the limiting dualism of Western thought along the way, he delivers a lucid, luminous vision for a different way of being: freer, more present, more whole.

The condition of today’s world cannot be transformed by technocratic rationality, since both technocracy and rationality are apparently nearing their apex; nor can it be transcended by preaching or admonishing a return to ethics and morality, or in fact, by any form of return to the past.

Gebser writes:

Who speaks of the future?

Who counts

in saying:

“It shall be”?

Look outward

and you see within:

It is.

If we do not overcome the crisis it will overcome us; and only someone who has overcome himself is truly able to overcome… Either time is fulfilled in us — and that would mean the end and death for our present earth and (its) mankind — or we succeed in fulfilling time: and this means integrality and the present, the realization and the reality of origin and presence.

Gebser anchors his argument in the fundament fact of time, out of which arises the poetic truth of the present:

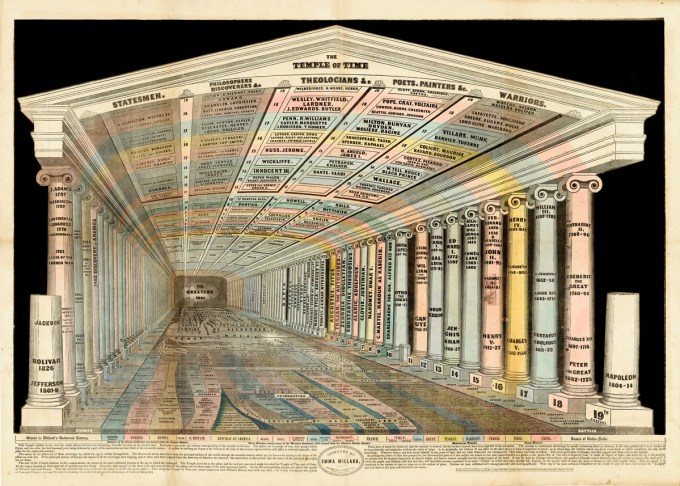

Looking back on the history of ideas — which is the history of our resistance to change, strewn with what David Byrne called “sleeping beauties”: creative and intellectual breakthroughs that lay dormant for centuries and millennia, rejected by their contemporaries, only to be affirmed and accepted epochs later — Gebser considers Democritus’s atomic theory, two millennia ahead of particle physics, and Zeno’s anticipation of relativity, worlds ahead of Einstein, and writes:

For seventeen years, through the next World War and its aftermath, he turned these ideas over in his mind, turned them into poetry and turned them into prose, eventually distilling them in the 1949 masterwork The Ever-Present Origin (public library) — an effort “to render transparent our own origin, our entire human past, as well as the present, which already contains the future.”

Origin is ever-present. It is not a beginning, since all beginning is linked with time. And the present is not just the “now,” today, the moment or a unit of time. It is ever-originating, an achievement of full integration and continuous renewal. Anyone able to “concretize,” i.e., to realize and effect the reality of origin and the present in their entirety, supersedes “beginning” and “end” and the mere here and now.

Acceptance and elucidation of the “new” always meets with strong opposition, since it requires us to overcome our traditional, our acquired and secure ways and possessions. This means pain, suffering, struggle, uncertainty, and similar concomitants which everyone seeks to avoid whenever possible.

The crisis we are experiencing today is not just… a crisis of morals, economics, ideologies, politics or religion. It is not only prevalent in Europe and America but in Russia and the Far East as well. It is a crisis of the world and mankind such as has occurred previously only during pivotal junctures — junctures of decisive finality for life on earth and for the humanity subjected to them. The crisis of our times and our world is in a process — at the moment autonomously — of complete transformation, and appears headed toward an event which… can only be described as a “global catastrophe.” … We must soberly face the fact that only a few decades separate us from that event. This span of time is determined by an increase in technological feasibility inversely proportional to man’s sense of responsibility — that is, unless a new factor were to emerge which would effectively overcome this menacing correlation.

He adds an essential disclaimer consonant with the basic ethos of The Marginalian, reverberating with the reason I spend my days and nights with long-gone visionaries like Gebser:

Writing at first for his own generation, Gebser came to find as the years unspooled into decades that the subject was not only timeless but rediscovered with ever-growing urgency by the next generation. In a passage of astonishing resonance for our own time, he observes: