So it is that any totality of love is born of the specifics — those footholds of understanding by which we ascend the ladder of appreciation and admiration to arrive at a particular and attentive love that subjectifies what it loves rather than objectifying it, the way Ursula K. Le Guin believed poetry subjectifies the universe.

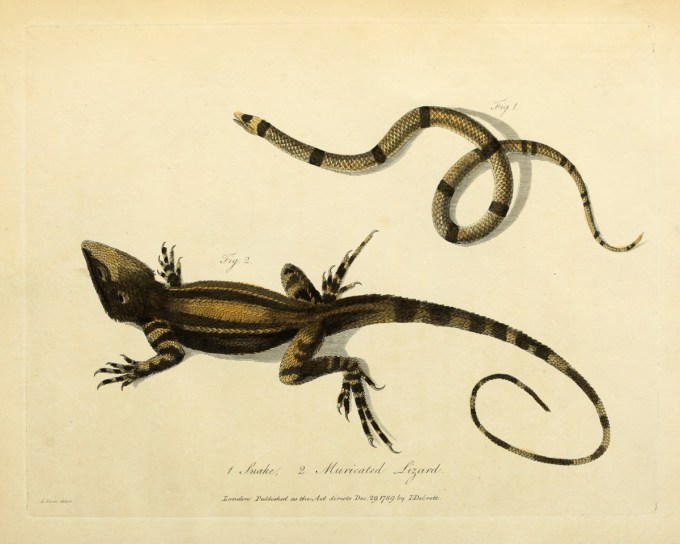

Inevitably, the creatures previously regarded as remote and abstract othernesses, caricatured by a few loathsome features, are gradually rendered interesting by the thousand small details of their being, complex and concrete. Because interest is the crucible of intimacy and intimacy the crucible of connection, because the light of attention cast upon the creatures renders them luminous golden threads indivisible from the tapestry of aliveness that makes our rocky planet an enchanted loom of a world, the poems inevitably become love poems.

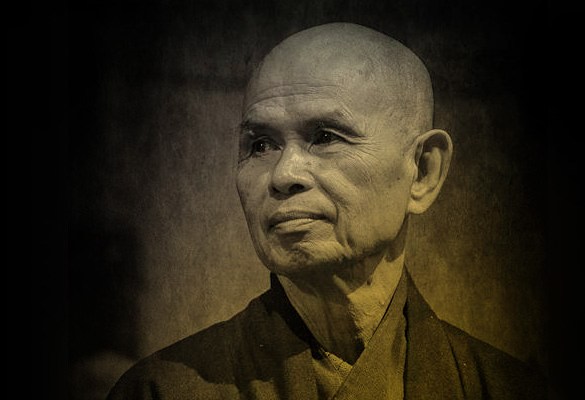

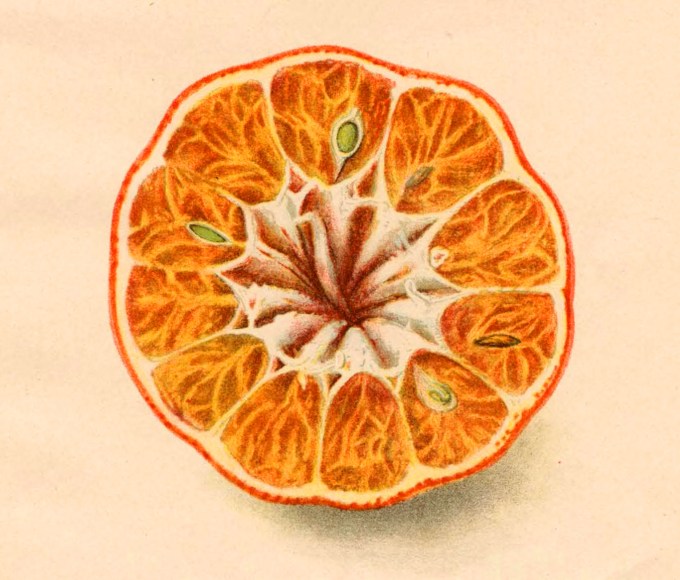

In a section of his 1992 classic Peace Is Every Step (public library) titled “Tangerine Meditation,” he observes that if you are offered a freshly picked tangerine, the magnitude of your enjoyment will depend on the level of your mindfulness:

He goes on to share a reality-regrounding mindfulness practice from his work with children that is, like a great children’s book, a miniature masterpiece of philosophy and a psychological salve for any stage of life:

For a different and equally potent take on how attention magnifies joy, drawing on a different orange fruit, savor Diane Ackerman’s sensual poem “The Consolation of Apricots,” then revisit Thich Nhat Hanh’s gentle and powerful wisdom on mastering the art of “interbeing” we call love, the four Buddhist mantras for turning fear into love, and his wonderful hugging meditation — which might just be the loveliest way for this world to stretch itself alive after the long contact-famished stupor of a global pandemic.

Each time you look at a tangerine, you can see deeply into it. You can see everything in the universe in one tangerine. When you peel it and smell it, it’s wonderful. You can take your time eating a tangerine and be very happy.

Echoing John Muir’s poetic observation that “when we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe,” Thich Nhat Hanh adds:

A quarter millennium after William Blake saw “a World in a Grain of Sand and a Heaven in a Wild Flower” and a century after William James laid the foundation of modern psychology with the then-radical assertion that your experience is what you agree to attend to, the great Vietnamese peace activist and Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh developed a simple, powerful instrument for refining attention, kindred to Marie’s poetic assignment, further miniaturized into a portable everyday aid for living with greater aliveness.

If you are free of worries and anxiety, you will enjoy [the tangerine] more. If you are possessed by anger or fear, the tangerine may not be very real to you.

One day, I offered a number of children a basket filled with tangerines. The basket was passed around, and each child took one tangerine and put it in his or her palm. We each looked at our tangerine, and the children were invited to meditate on its origins. They saw not only their tangerine, but also its mother, the tangerine tree. With some guidance, they began to visualize the blossoms in the sunshine and in the rain. They saw petals falling down and the tiny fruit appear. The sunshine and the rain continued, and the tiny tangerine grew. Now someone has picked it, and the tangerine is here. After seeing this, each child was invited to peel the tangerine slowly, noticing the mist and the fragrance of the tangerine, and then bring it up to his or her mouth and have a mindful bite, in full awareness of the texture and taste of the fruit and the juice coming out. We ate slowly like that.

My poet friend Marie Howe gives the students in her ecopoetry class a lovely assignment: At the outset of the semester, each young poet is asked to name the animal they find most repulsive, then to learn everything they can about it — scientifically, historically, culturally. By the conclusion of the course, they have to write a poem about it.

Attention, after all, is the native poetry of consciousness and the most elemental form of love.