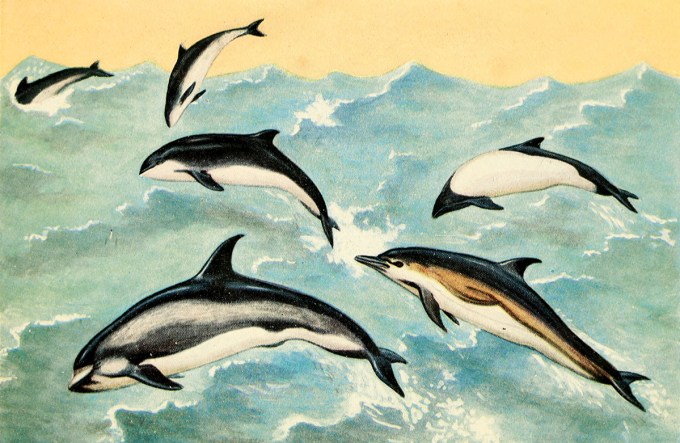

This sonic wonder is part and parcel of the same evolutionary inheritance that gave cetaceans an input channel as astonishing to us as the output of suprasonic hieroglyphics: their capacity for echolocation, conferred by jaws that serve as high-definition sonograms.

Dolphins can detect the shape, position, and size of larger objects from up to six miles away. Their echolocation is so powerful and sensitive that it can penetrate over a foot deep into sand; it can even “see” beneath skin. Dolphins can peer into the lungs, stomachs, and brains of the animals around them. With all this information, scientists believe dolphins can create the equivalent of an HD-quality rendering of objects nearby — not only where these objects are, but how they look from the inside out. In essence, dolphins and other cetaceans have X-ray vision.

Except it is only truly quiet if we limit truth to our human perceptions. Down in the indigo waters, in what Else Bostelmann called “the submarine fairyland” as she brought the undersea world to the human eye for the first time, symphonies of speech mute to us bellow across immense distances, carrying messages as urgent and delicate as danger and identity. Now, a century of science and compassionate curiosity later, we know that dolphin mothers will whistle a sound patter over and over to a newborn — a kind of christening, imprinting the baby with its given name.

In his altogether fascinating book Deep: Freediving, Renegade Science, and What the Ocean Tells Us About Ourselves (public library), James Nestor writes:

Dolphins don’t have vocal cords or larynxes, so they can’t vocalize in a way that sounds like human speech. Instead, they use two small mouth-like structures embedded in their heads — vestiges of what were once nostrils. The dolphin can flex and bend these nasal passages, called phonic lips, to create a variety of sounds — whistles, burst pulses, clicks, and more — in frequencies that range between 75 and 150,000 Hz.

So it is that an extraordinary underwater language remained undetected by humans for the vast majority of the history of our species and the history of our science.

In a world of seven billion people, where every inch of land has been mapped, much of it developed, and too much of it destroyed, the sea remains the final unseen, untouched, and undiscovered wilderness, the planet’s last great frontier… the last truly quiet place on Earth.

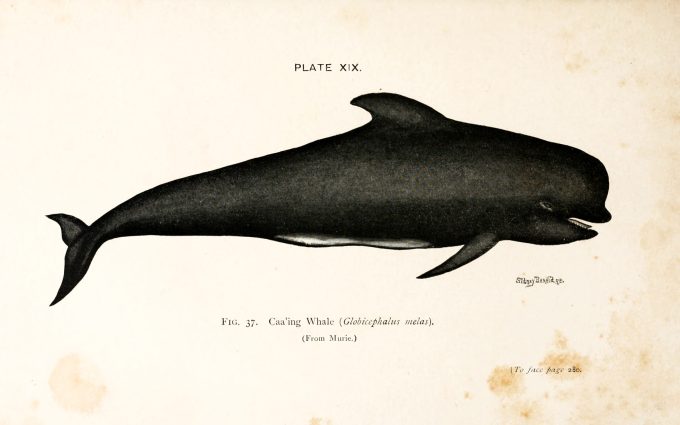

Sound doesn’t travel in a straight line, the way it looks on a spectrogram, but instead expands in three dimensions, like a mist. Ears only process sound from two channels; cetaceans have the equivalent of thousands of channels that can collect this mist from all directions… For humans to perceive sonographic images through echolocation isn’t easy. Scientists would need to construct an artificial jaw filled with thousands of little microphones to mimic the tiny receptors, then build a computer capable of processing all the data collected.

“Words are events, they do things, change things… they feed energy back and forth and amplify it,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in her uncommon ode to the magic of real communication. “They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it.”

What to us is nothing less than a miracle, demanding an epic triumph of technology, is to cetaceans nothing more than a commonplace of survival amid a pitch-black world. Nestor describes the splendid otherness of the physiology that renders these mammals of the undersea both kin and alien:

Dolphins and whales — the aquatic mammals collectively known as cetaceans — have some of the largest and most complex brains on our pale blue dot. A century after the great nature writer Henry Beston called on us to rise to a different and wiser concept of animals, for they move through this world “gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear,” we know that the dolphin neocortex — the part of the brain tasked with problem-solving and higher-order thinking — is proportionately larger than ours, and that dolphins communicate in a strange and wondrous language we are only just beginning to decipher. Nestor details the dazzling creaturely mechanics of its magic:

Nestor considers just how alien this form of listening is to us and what leaps in scientific ingenuity it would require for us to create a mechanical prosthesis that extends our creaturely capabilities to such Bestonian levels of suprahuman senses:

Complement with the wondrous world of octopus consciousness and the science of how trees communicate, even newer to us and our scientific tools than the science of cetacean communication, then revisit Year of the Whale — the poetic 1969 book about the mysterious lives of our planet’s largest creatures — and artist Jenni Desmond’s tender science serenade to the blue whale.

When a cetacean sends out a click (its version of a sonar ping), it receives the echo information with a fatty sac located beneath the lower jaw. Unlike ears, which provide only two directional sources to gather information, this fatty sac provides the cetacean with thousands of data points. The animal can process these to gauge the distance, shape, depth, interior, and exterior of the objects and creatures around it.

From the moment we first looked up at the night sky and declared the scattering of stars to be the totality of the universe, placing ourselves at its center, over and over we have mistaken the limits of our sense-perception for the limits of all there is; over and over, our creaturely limitations have limited our grasp of reality.

Of these, we can only hear the slenderest fraction in the lowest register — while humans can produce sounds up to 20,000 Hz, our everyday speech falls into the paltry 85-300 Hz range. But one of the most extraordinary things about our species is our stubborn, inspired refusal to let our creaturely givens confine our imagination and our hunger for truth. “We have a hunger of the mind which asks for knowledge of all around us,” the pioneering astronomer Maria Mitchell observed when a new generation of powerful telescopes began revealing cosmic truths far beyond what our naked eyes could see, “and the more we gain, the more is our desire.”

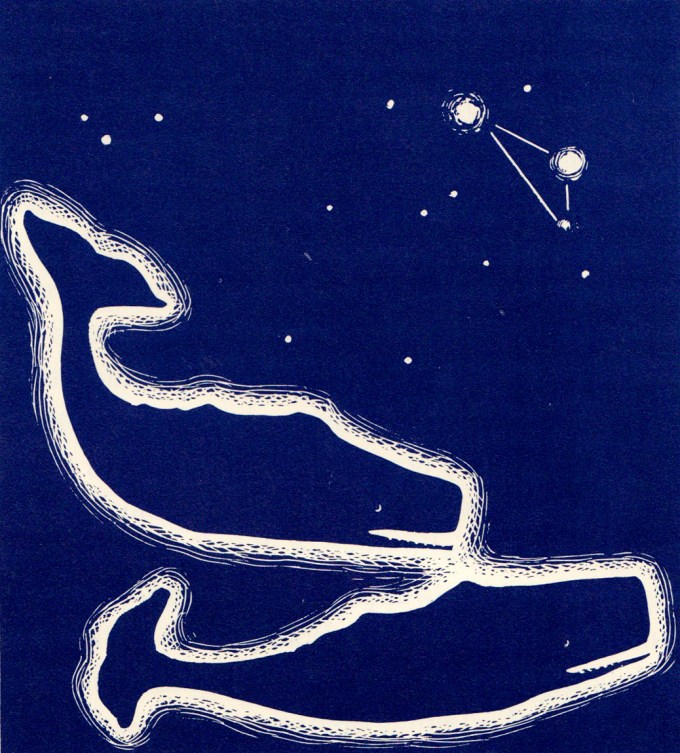

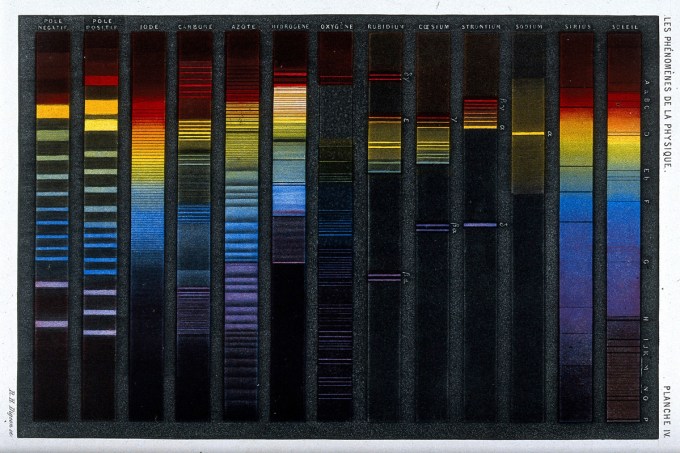

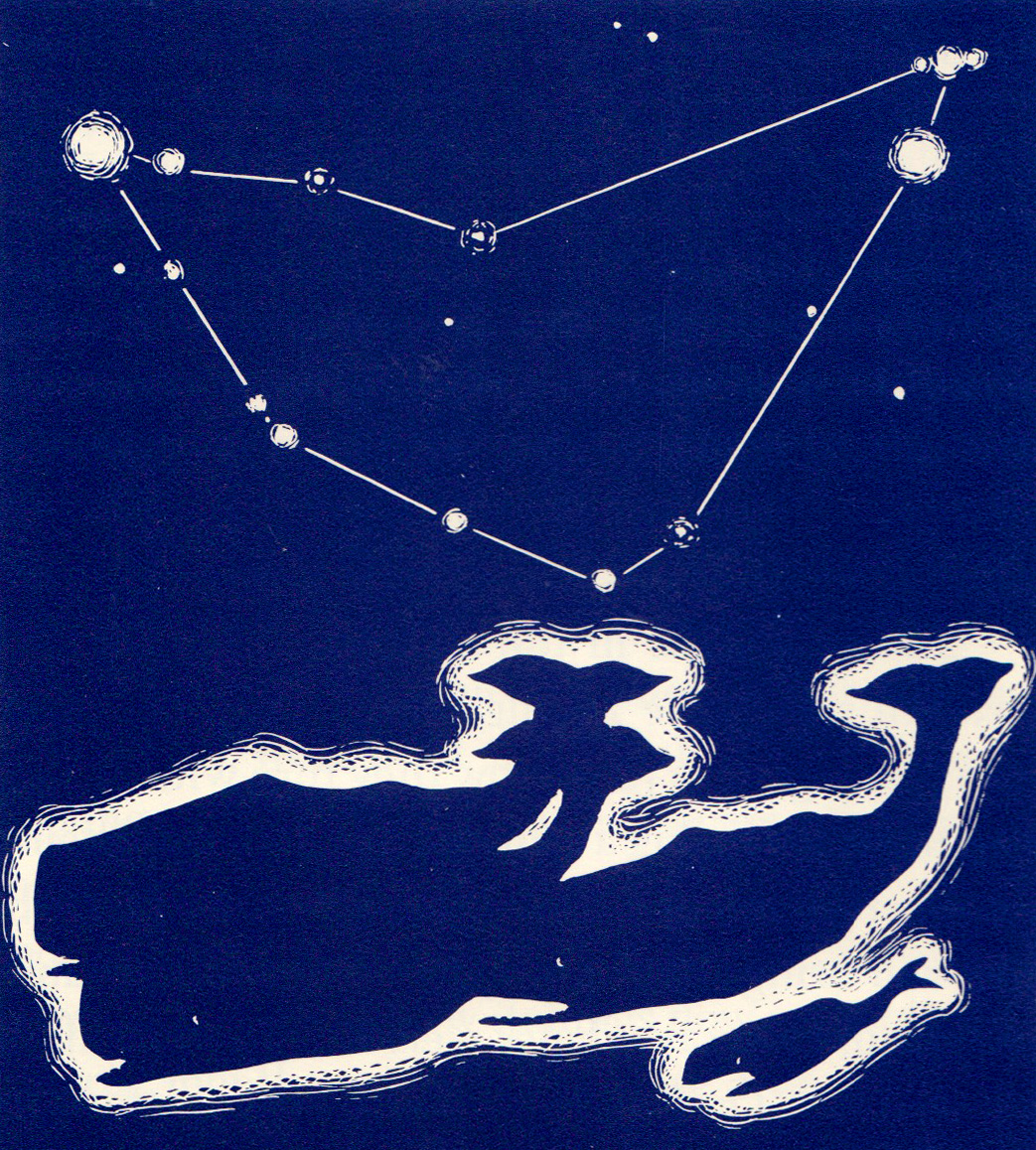

It was a tool of her era, invented for her field — the spectrograph, first used to analyze the light of Vega, the star that a quarter millennium earlier had anchored one of Galileo’s most ingenious experiments refuting the geocentric model of the universe — that scientists applied to sound a century later to detect and decode the language of underwater mammals. Recording the high-frequency clicks and whistles of dolphins, inaudible to human ears, and playing the recordings back through a spectrogram, humans were able to perform a feat of mechanical synesthesia and see for the first time the sound of language-rich silence — sound waves that looked, in Nestor’s lovely poetic image, like “a primitive form of hieroglyphics.”

For millennia, we have considered language — the magic-box of words — the hallmark of our species. Only in the last blink of evolutionary time have we begun to override our self-referential nature and consider the possibility that other types of channels might carry the magical energy of creatures telling each other what it is like to be alive, in the here and now of a shared reality.