“Practice kindness all day to everybody and you will realize you’re already in heaven now,” Jack Kerouac half-resolved, half-instructed an epoch later in a beautiful letter to his first wife and lifelong friend.

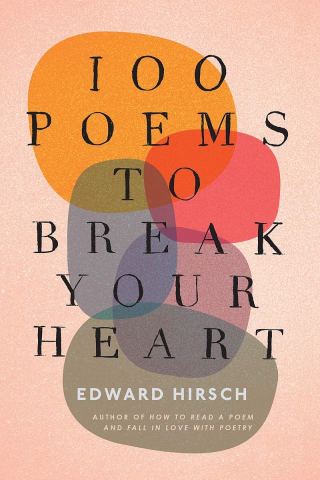

In 1978, drawing on a jarring real-life experience, Naomi Shihab Nye captured this difficult, beautiful, redemptive transmutation of fear into kindness in a poem of uncommon soulfulness and empathic wingspan that has since become a classic — a classic now part of Edward Hirsch’s finely curated anthology 100 Poems to Break Your Heart (public library); a classic reimagined in a lovely short film by illustrator Ana Pérez López and my friends at the On Being Project:

Of course, even the best-intentioned of us are not capable of perpetual kindness, not capable of being our most elevated selves all day with everybody. If you have not watched yourself, helpless and horrified, transform into an ill-tempered child with a loved one or the unsuspecting man blocking the produce aisle with his basket of bok choy, you have not lived. Discontinuous and self-contradictory even under the safest and sanest of circumstances, human beings are not wired for constancy of feeling, of conduct, of selfhood. When the world grows unsafe, when life charges at us with its stresses and its sorrows, our devotion to kindness can short-circuit with alarming ease. And yet, paradoxically, it is often in the laboratory of loss and uncertainty that we calibrate and supercharge our capacity for kindness. And it is always, as Kerouac intuited, a practice.

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to mail letters and purchase bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for,

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.

KINDNESS

by Naomi Shihab Nye

“Nothing can make our life, or the lives of other people, more beautiful than perpetual kindness,” Leo Tolstoy — a man of colossal compassion and colossal blind spots — wrote while reckoning with his life as it neared its end.

[embedded content]

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness,

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

Complement with a fascinating cultural history of how kindness became our forbidden pleasure, Jacqueline Woodson’s letter to children about how we learn kindness, and George Sand’s only children’s book — a poignant parable about choosing kindness and generosity over cynicism and fear — then revisit other soul-broadening animated poems: “Singularity” by Marie Howe, “Murmuration” by Linda France, and “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry.

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.