With an eye to the limitation of these words — of all words — as “the primary and somehow insignificant expression of a fulfillment,” Barthes adds with a conspiratorial wink:

This renders the exchange of I love you’s — that coveted contract of mutuality — a strange sort of transaction, currency encrypted with change, with the loneliness and loveliness of change: In any love worthy of the name, the I and the you are ever-changing, so that the love binding the two is ever-renewing. But perhaps the strangest and most lonely-making aspect of I love you is that it traps the boundlessness of love in the limits language, as narrow and straining a conduit of love as the crack in the wall between Pyramus and Thisbe.

Complement with Robert Browning — one of those rare romantic poets who rose above Barthes’s indictment — on saying I love you only when you mean it and Rainer Maria Rilke — one of those rare post-romantic poets who refused to treat romance as a transaction of conveniences — on what it really means to mean it, then revisit philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s Proust-fomented litmus test for how you really know you love somebody and Adrienne Rich on earning the right to use the word love.

There’s no help for it: I love you is a demand: hence it can only embarrass anyone who receives it, except the Mother — and except God!

I decide that [the declaration of love], though I repeat and rehearse it day by day through the course of time, will somehow recover, each time I utter it, a new state. Like the Argonaut renewing his ship during his voyage without changing its name, the subject in love will perform a long task through the course of one and the same exclamation, gradually dialecticizing the original demand though without ever dimming the incandescence of its initial address, considering that the very task of love and of language is to give to one and the same phrase inflections which will be forever new.

A hundred pages into the book’s larger meditation on the limits of language — our primary tool for narrating our inner lives so that we can understand ourselves and be understood — Barthes writes:

But then Barthes considers “a delicate way out of the maze.” In an allusion to the Ship of Theseus — the brilliant ancient Greek thought experiment exploring what makes you you — he intimates that the only thing which makes love love is its self-renewal in the consciousness of the lover despite the self-exhausting loops of its declaration:

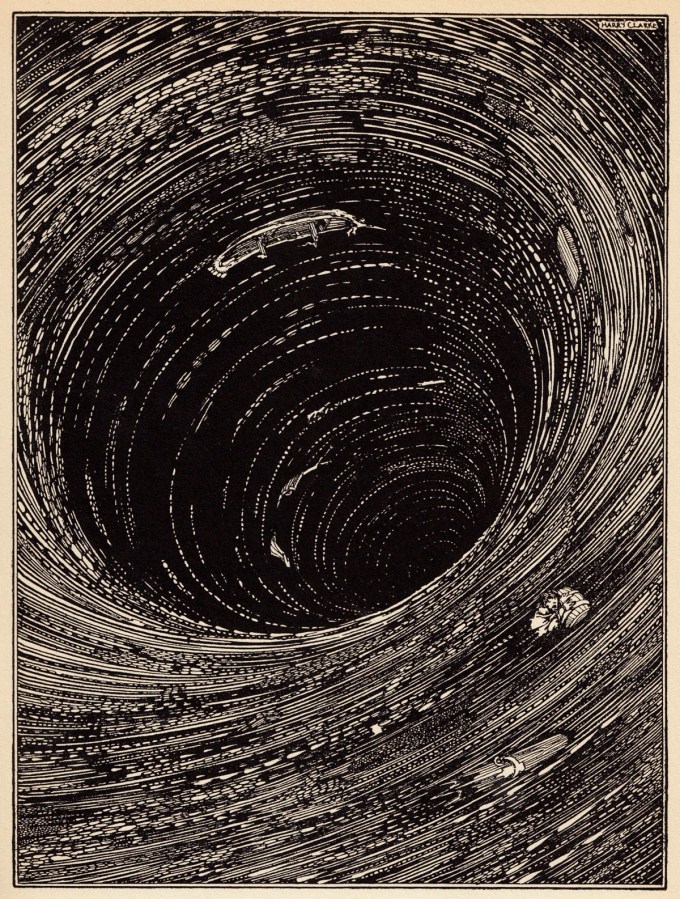

Does not this whole paroxysm of love’s declaration conceal some lack? We would not need to speak this word, if it were not to obscure, as the squid does with his ink, the failure of desire under the excess of affirmation.

All (romantic) poetry and music is in this demand: I love you, je t’aime, ich liebe dich! But if by some miracle the jubilatory answer should be given, what might it be? What is the taste of fulfillment?

Unless I should be justified in flinging out the phrase in the improbable but ever hoped-for case when two I love you‘s, emitted in a single flash, would form a pure coincidence, annihilating by this simultaneity the blackmail effects of one subject over the other: the demand would proceed to levitate.

When I walk — which I do every day, as basic sanity-maintenance, whether in the forest or the cemetery or the city street — I walk the same routes, walk along loops, loops I often retrace multiple times in a single walk. This puzzles people. Some simply don’t get the appeal of such recursiveness. Others judge it as dull. But I walk to think more clearly, which means to traverse the world with ever-broadening scope of attention to reality, ever-widening circles of curiosity, ever-deepening interest in the ceaselessly flickering constellation of details within and without. In this respect, walking is a lot like love — for one human being to love another is to continually discover new layers of oneself while continuously discovering new layers of the other, and in them new footholds of love.

Thinking about this on one of my cemetery loops, because the act of walking is also a mighty machete for clearing the pathways of memory overgrown with life, I suddenly remembered a passage by the French semiotician and philosopher Roland Barthes (November 12, 1915–March 26, 1980) from his superb 1977 part-autobiography, part-rebellion against the conventions of life and of the telling of life-stories, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes (public library) — the playful, profound, blazingly original self-interrogation that gave us his existential catalogue of likes and dislikes.