It was not, of course, human. I was deep, deep below the time of man* in a remote age near the beginning of the reign of mammals. I squatted on my heels in the narrow ravine, and we stared a little blankly at each other, the skull and I. There were marks of generalized primitiveness in that low, pinched brain case and grinning jaw that marked it as lying far back along those converging roads where… cat and man and weasel must leap into a single shape.

With an eye to the heedful opposable thumbs excavating the skull, he adds:

It can pivot a hard day to remember that we are “atoms with consciousness… matter with curiosity.” But for all of its innumerable glories, consciousness comes with a price that can be difficult to bear — consciousness, with its immense capacity for love, and for loneliness.

Out of this awareness Eiseley wrests the supreme reward of consciousness — its irrepressible impulse to make meaning out of indifferent fact. In consonance with Alan Watts’s assertion that “if the universe is meaningless, so is the statement that it is so [for] the meaning and purpose of dancing is the dance,” he writes:

We must bear it all, as we watch our humanity and its crowning cognitive achievement dishonored by superstition and senseless violence and cruelties of which no other animal is capable, finding it more and more difficult to take pride in our evolutionary inheritance.

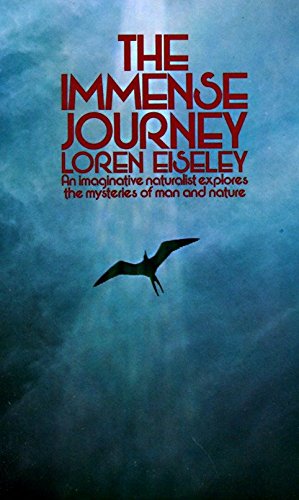

Complement this fragment of the endlessly perspectival The Immense Journey with Eiseley on the muskrat as a lens on the meaning of life, then revisit his equally poetic and kindred-minded contemporary Lewis Thomas on how to live with our human fragility.

It is not a bad symbol of that long wandering, I thought again — the human hand that has been fin and scaly reptile foot and furry paw.

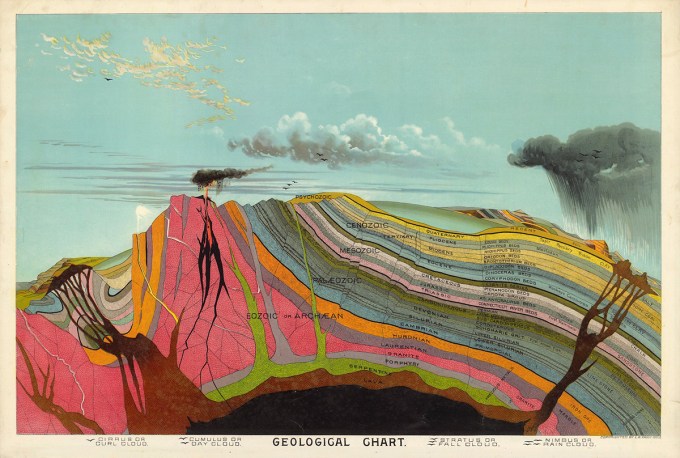

Perhaps the Slit, with its exposed bones and its far-off vanishing sky, has come to stand symbolically in my mind for a dimension denied to man, the dimension of time. Like the wistaria on the garden wall he is rooted in his particular century. Out of it — forward or backward — he cannot run. As he stands on his circumscribed pinpoint of time, his sight for the past is growing longer, and even the shadowy outlines of the galactic future are growing clearer, though his own fate he cannot yet see. Along the dimension of time, man, like the rooted vine in space, may never pass in person. Considering the innumerable devices by which the mindless root has evaded the limitations of its own stability, however, it may well be that man himself is slowly achieving powers over a new dimension — a dimension capable of presenting him with a wisdom he has barely begun to discern. Through how many dimensions and how many media will life have to pass? Down how many roads among the stars must man propel himself in search of the final secret? The journey is difficult, immense, at times impossible, yet that will not deter some of us from attempting it… We have joined the caravan, you might say, at a certain point; we will travel as far as we can, but we cannot in one lifetime see all that we would like to see or learn all that we hunger to know.

Perhaps there is no meaning in it at all, the thought went on inside me, save that of journey itself, so far as men can see. It has altered with the chances of life, and the chances brought us here; but it was a good journey — long, perhaps — but a good journey under a pleasant sun. Do not look for the purpose. Think of the way we came and be a little proud. Think of this hand — the utter pain of its first venture on the pebbly shore.

The skull lay tilted in such a manner that it stared, sightless, up at me as though I, too, were already caught a few feet above him in the strata and, in my turn, were staring upward at that strip of sky which the ages were carrying farther away from me beneath the tumbling debris of falling mountains. The creature had never lived to see a man, and I, what was it I was never going to see? … I thought, as I patiently began the task of chiseling into the stone around the skull, I would never again excavate a fossil under conditions which led to so vivid an impression that I was already one myself. The truth is that we are all potential fossils still carrying within our bodies the crudities of former existences, the marks of a world in which living creatures flow with little more consistency than clouds from age to age.

Eiseley meets the bygone creature with a jolt of perspective:

In a passage nothing less than countercultural today, when we live entombed in the news cycle of a perpetual present, he adds:

On those days when the costs of consciousness mount to heavy the heart, when I long to fall in love again with being human, I return to some calibrating passages by the poetic anthropologist and naturalist Loren Eiseley (September 3, 1907–July 9, 1977) from his altogether transcendent 1957 book The Immense Journey (public library) — his record of “the prowlings of one mind which has sought to explore, to understand, and to enjoy the miracles of this world, both in and out of science.”

To remember this, just like remembering that we only exist because of flowers, is to allow an awareness that reaches beyond cerebral knowledge and into some deep creaturely gladness that, in an instant, makes you feel connected to everything else alive, grateful to be part of this immense living symphony of time and chance.

Descending into an enormous slit in Earth’s crust — “a perfect cross section through perhaps ten million years of time” — in search of fossils, Eiseley describes the skull he discovers entombed in stone several million years down this chute of time: