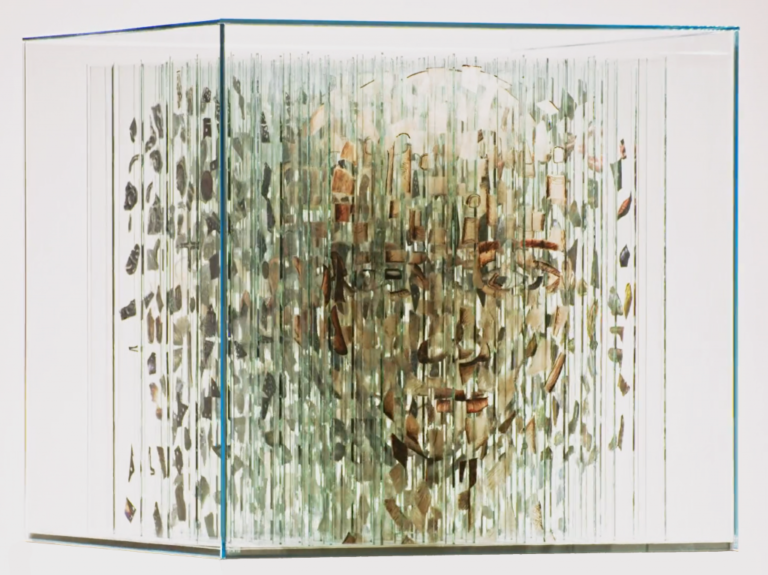

[Self-portrait of PFC Archie Sweetman, carved into the wall of the WWI soldier’s underground living space while at war in France. Photo by Jeff Gusky.]

It was 2005, and I was an embedded advisor to the newly-formed Iraqi Army in Fallujah, Iraq. Fallujah was terribly violent, which made the urban battlefield a morally treacherous place. There was a potential moral dilemma waiting behind every door and lurking around every corner. I discovered late one night that our Iraqi counterparts had detained a journalist for criticizing the government. I was forced to choose between upholding my liberal values and maintaining a strong relationship with the Iraqi soldiers that our team had to trust with our lives. I spent lonely nights contemplating the things I saw and did. It wasn’t long before I started to feel my humanity slip away.

While I was home on mid-tour leave, I took refuge at a local bookstore. I wandered into the philosophy section, searching for something that might help ground my morality. Knowing little about philosophy, I chose a book based solely on its title. The book was Practical Ethics by Peter Singer. Reading Singer’s book at night in my room in downtown Fallujah sparked a deep interest in philosophy that I hadn’t known was there.

During the Vietnam War, Rawls argued that the draft exposed structural racial injustice because it disproportionately burdened black Americans in a way that violated the norms of fair cooperation in a society. Middle-class Americans and children of military veterans disproportionately fought the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. While many in our discipline rightly object to how our military has been used over the last twenty years, it’s crucial to separate the soldiers from the wars our country sent us to fight.

How Military Veterans Contribute to Academic Philosophy

by Jesse Hamilton

The path to college wasn’t easy for many undergraduate student veterans. High school graduates from low-income families often enlist out of necessity. Few held a college acceptance letter in one hand and enlistment papers in the other and chose the latter. It’s safe to assume that many veterans aren’t inclined towards majoring in philosophy. Many front-line military leaders steer service members towards majors like finance and computer science because that’s where the money is. This message resonates with soldiers from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Soldiers trust their leaders and make life decisions based on the guidance they receive. Talking to student veterans about majoring or minoring in philosophy may help them recognize the richness philosophy can add to their lives and the contributions that they can bring to the discipline.

Before becoming a philosopher, Descartes studied and then taught military engineering as a soldier. Wittgenstein penned the Tractatus as an artilleryman in World War I and sent out his manuscript while confined at a prisoner of war camp in Italy. Quine was a codebreaker during World War II, while Davidson trained spotters to distinguish Allied planes from Axis planes. Rorty, Marcuse, Carnap, Heidegger, Feyerabend, and Dummett all served in the armed forces before beginning their careers in philosophy.

Soldiers in combat often contemplate some of life’s most pressing questions. Our discipline benefits from people who have done the kind of life-examination that Socrates, a veteran of the Peloponnesian War, thought philosophy was all about. War also motivates some soldiers to ask questions they hadn’t yet considered. And those might be important questions in philosophy. As John Rawls explains:

Military veterans have much to contribute to philosophy at all levels of the discipline. As students, veterans can bring an additional layer of experience and further tools for exploring topics like authority, use of force, moral dilemmas, political violence, and how to address human rights abuses. Similarly, we can illuminate the power of nationalism and propaganda to influence personal decisions and mobilize collective action. As teachers, veterans bring unique and useful leadership experience. Motivating others is a core competency in the military. Lessons learned leading soldiers through a deployment overseas can be adapted to the classroom. Veterans skilled in the military’s methods of instruction and knowledge transfer can diversify philosophy’s pedagogy.

Tomorrow is Veterans Day in the United States.

In the following guest post*, Jesse Hamilton, a Ph.D. student in philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, recounts his journey from Fallujah to philosophy and suggests that military veterans have much to contribute to academic philosophy.

From the beginning of my study of philosophy in my late teens I have been concerned with moral questions and the religious and philosophical basis on which they might be answered. Three years spent in the US Army in World War II led me to be also concerned with political questions. Around 1950 I started to write a book on justice, which I eventually completed.

I arrived at the Academy fifteen years after that trip to the bookstore. Despite my passion for philosophy, I suspected that my military training might hinder my academic pursuits. Unlike philosophers, soldiers aren’t trained to think critically. Instead, we’re trained to execute lawful orders swiftly and without question. We tackled problems with “eighty percent solutions” because perfection was the enemy of progress. While eighty percent solutions are effective in time-sensitive environments like training and combat, eighty percent valid arguments don’t pass muster. I feared that the way the Army conditioned me to think and solve problems was a dealbreaker. However, I came to learn that my military experience contained key insights that have proven valuable in studying philosophy.