The Botany of Desire — which also gave us the story of how “broken tulips” shaped the modern world — is thoroughly satisfying in its totality. Complement this fragment with the little-known botanical-cultural story of why NYC is known as “the Big Apple” — a surprise even to most native New Yorkers — then revisit Pollan on how one particular plant magnified the bewitchment of Bach.

This defiant aspect of gardening, so foreign to the dominant modern model of the garden as a place of order walled within a lawn-mowed wilderness, is what Michael Pollan explores in a portion of his 2001 classic The Botany of Desire (public library).

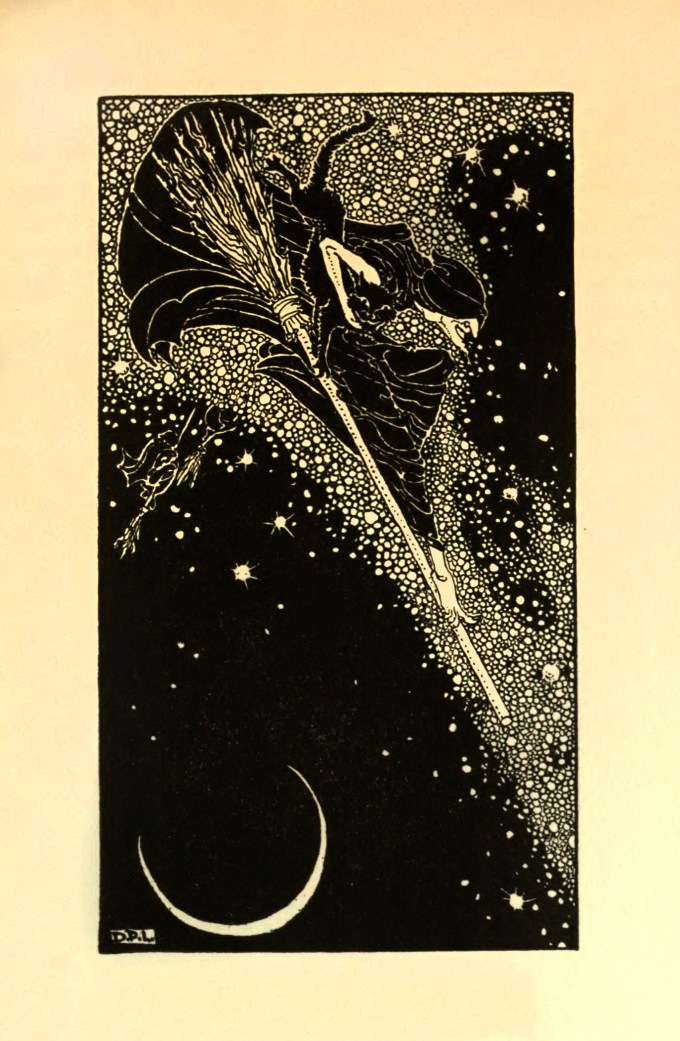

In ancient times, people all over the world grew or gathered sacred plants (and fungi) with the power to inspire visions or conduct them on journeys to other worlds; some of these people, who are sometimes called shamans, returned with the kind of spiritual knowledge that underwrites whole religions. The medieval apothecary garden cared little for aesthetics, focusing instead on species that healed and intoxicated and occasionally poisoned. Witches and sorcerers cultivated plants with the power to “cast spells” — in our vocabulary, “psychoactive” plants. Their potion recipes called for such things as datura, opium poppies, belladonna, hashish, fly-agaric mushrooms (Amanita muscaria), and the skins of toads (which can contain DMT, a powerful hallucinogen). These ingredients would be combined in a hempseed-oil-based “flying ointment” that the witches would then administer vaginally using a special dildo. This was the “broomstick” by which these women were said to travel.

It was in one such epoch that Johannes Kepler took six years from decoding the laws of the universe to defend his herbalist-mother in a witchcraft trial, while elsewhere in Europe the world’s first prim and proper botanical gardens were sprouting up.

Gardening as witchcraft for the soul — defying the permissible, magnifying the possible.

For most of their history, after all, gardens have been more concerned with the power of plants than with their beauty — with the power, that is, to change us in various ways, for good and for ill.

But for most of the history of our species, the relationship between nature and human nature has been one of conviviality rather than conquest and control. Only in the mere blink of evolutionary time called modern civilization did we begin viewing the rest of nature as a “parallel world.”

Long Years apart — can make no

Breach a second cannot fill —

The absence of the Witch does not

Invalidate the spell —

As a gardener and a poet, ever since she pressed four hundred wildflowers into the teenage herbarium that became her first formal act of composition, Emily Dickinson had an uncommon grasp of how the life of plants and the life of feelings interleave — particularly the forbidden, the subversive, the countercultural.

He writes:

In many ways, across epochs and cultures, gardens themselves — and not only the plants grown in them — have served as psychoactive agents profoundly transforming the human experience: gardening as resistance, gardening as growing through grief, gardening as finding the roots of happiness, gardening as “an exercise in supreme attentiveness.”

“Oh that beloved witch-hazel,” Emily Dickinson wrote to her cousins in 1876 as she tended to her famous garden, “one loved stalk as hearty as if just placed in the mail by the woods… witch and witching too, to my joyful mind” — her garden, across the hedge from which lived the love of her life, joylessly married to Emily’s brother, absent from Emily’s arms for a quarter century. That same year, she wrote in a poem:

I sometimes think we’ve allowed our gardens to be bowdlerized, that the full range of their powers and possibilities has been sacrificed to a cult of plant prettiness that obscures more dubious truths about nature, our own included.

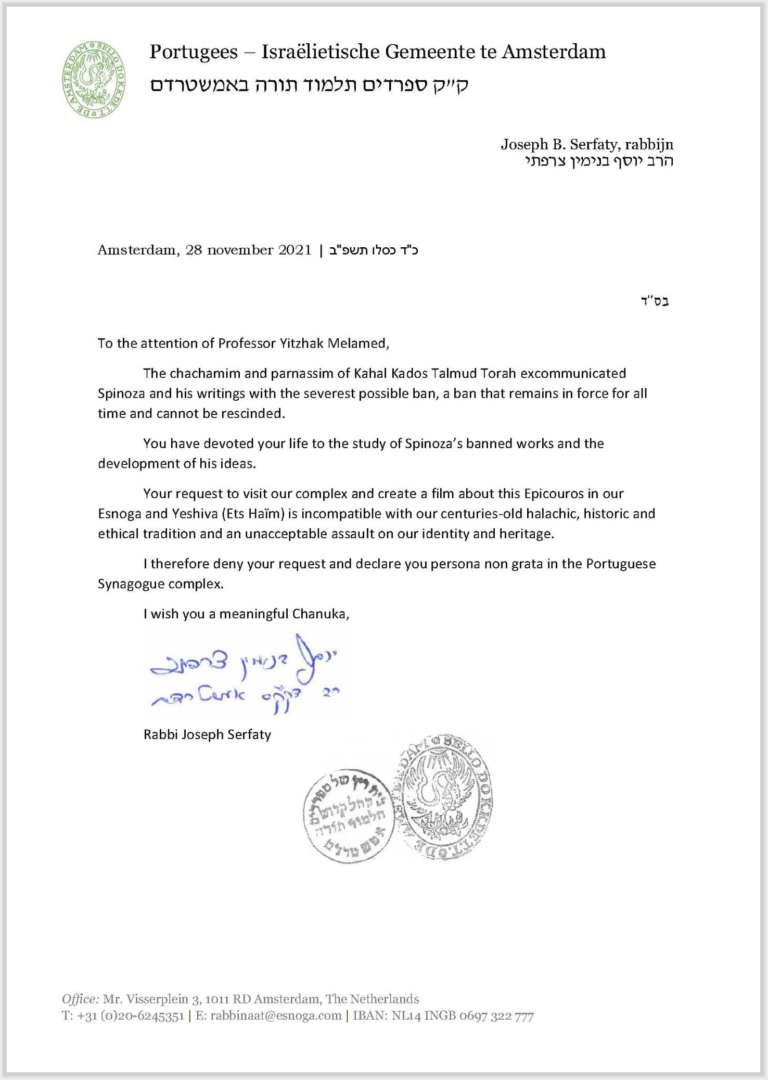

Pollan envisions a future that might view our present conception of the garden — a place for basic produce, household herbs, and pretty flowers — as “almost Victorian in its repressions and elisions,” which include the modern repression and elision of the garden’s radical past. He traces the subversive botanical roots of the mythic flying witch’s broomstick as one example: