Particularly I remember the unique purity of the light, which gave to every variation of every colour an individual vitality and which lucidly emphasised every line, curve and angle. Here, for the first time, I became fully aware of light as something positive, rather than as a taken-for-granted aid to perceiving objects.

On the following morning came one of the most glorious experiences of the entire journey — a fifteen-mile cycle-run in perfect weather around the base of Mount Ararat. This extraordinary mountain, which inspires the most complex emotions in the least imaginative traveller, affected me so deeply that I have thought of it ever since as a personality encountered, rather than a landscape observed… Cycling day after day beneath a sky of intense blue, through wild mountains whose solitude and beauty surpassed anything I had been able to imagine during my day-dreams about this journey.

At the valley’s end my road started to climb the mountains, sweeping up and up and again up, in a series of hairpin bends that each revealed a view more wild and splendid than the last.

Beneath all the physical dirt and moral corruption there is an elegance and dignity about life here which you can’t appreciate at first, while suffering under the impact of the more obvious and disagreeable national characteristics. The graciousness with which peasants greet each other and the effortless art with which a few beautiful rags and pieces of silver are made to furnish and decorate a whole house — in these and many other details Persia can still teach the West. I suppose it’s all a question of seeing one of the oldest and richest civilisations in the world long past its zenith.

As I rode on he passed me and yelled: “You are a goddam nut-case!”

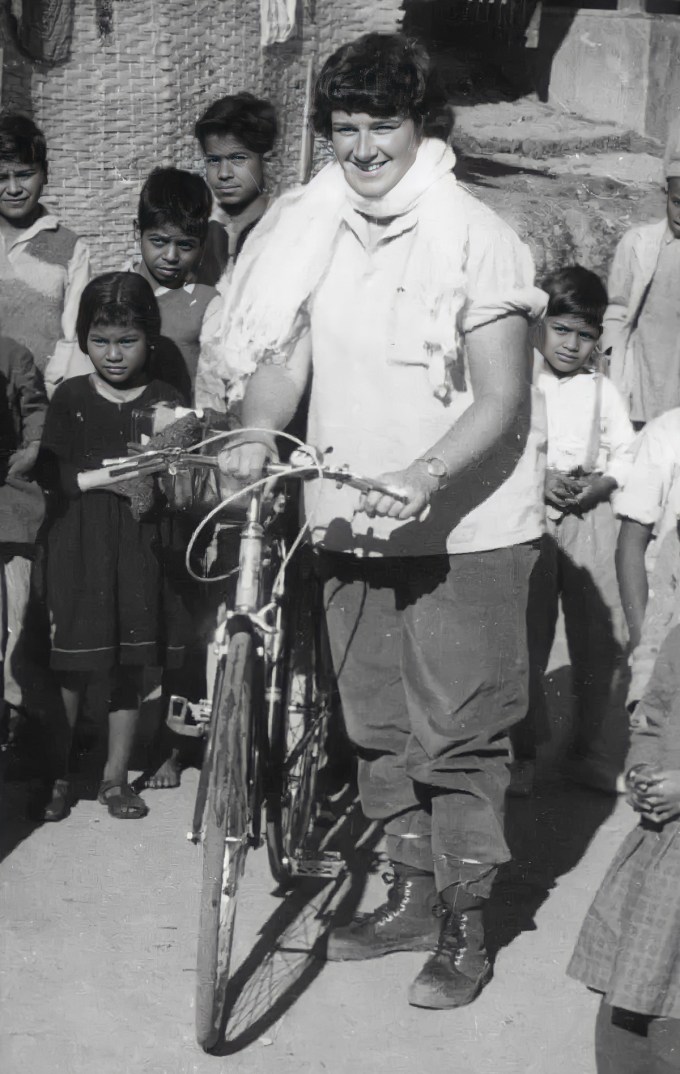

Over and over, it seems like Murphy’s bright spirit is her natural amulet against misfortune. Stopping by to rest at a local village, she reaches across the barrier of language, culture, and age to reduce the local children to giggles by pretending to be a sheepdog, before metamorphosing into a donkey to crawl around the sand on all fours with three toddlers or her back.

She departs with only a saddlebag of luggage, containing her passport and camera, a map, one spare pair of nylon pants and nylon shirt, toothbrush, comb, writing paper, two pens, and a copy of Blake’s poems.

Sometimes the enchantment of nature almost blinds her to the menacing brutalities of its forces. In one of myriad passages that radiate both her felicitous spirit and her tender relationship with her bicycle as an anthropomorphized companion — relatable relations for those of us who live on two wheels — she writes:

What a wonderful place this world is!

I regard this sort of life, with just Roz and me and the sky and the earth, as sheer bliss.

A century and a half later, another indomitable spirit of uncommon sensitivity to beauty, in nature and in human nature, took those dirt roads and wound them halfway around the world, discovering the romance of reality along the way.

In the early nineteenth century, the teenage Mary Godwin and her not-yet-husband Percy Bysshe Shelley left England for the Continent, traveling by foot and by mule, on the wings of love and youth. Through their constant poverty and hunger, through the frequent accidents and illnesses, they slaked their souls on beauty — on the shimmering grandeur of mountains and rivers, fiery sunsets and moonlit nights. It was on those dirt roads, under those open skies, that they became Romantics.

On the morning of my third day in Belgrade, there came a rise in temperature that not merely eased the body but relaxed the nerves. Never shall I forget the joy of standing bareheaded in my host’s front garden, watching tenuous, milky clouds drifting across the blue sky.

On the morning of my third day in Belgrade, there came a rise in temperature that not merely eased the body but relaxed the nerves. Never shall I forget the joy of standing bareheaded in my host’s front garden, watching tenuous, milky clouds drifting across the blue sky.

And off she goes, into the hinterland, her heart heavy with the news that two women have just been killed in the Mullah-provoked riots against women’s emancipation. Once again she turns to the nonhuman consolations of nature in this uncommonly beautiful corner of the globe:

Even through the slow and difficult climb to Herat — a city “as old as history and as moving as a great epic poem” — she drinks in the beauty that remains her most steadfast fuel along the grueling journey:

Again my knock remained unanswered, but this time, when I opened a door leading out of the hall, I found a policeman happily dozing by the stove, with a cat and two kittens on his lap. I immediately diagnosed that he was a nice policeman, and when I had gently roused him, and he had recovered from the shock of being required to function officially, I had my diagnosis confirmed.

Everywhere she goes, she is a spectacle — some have never seen a bicycle, some have never seen a lone woman traveller, and none have never seen, nor could even conceive of, a woman traveling the world alone on a bicycle. In her baggy hand-me-down shirt and boots donated by the U.S. Army in the Middle East, she is often taken for a man — because, she speculates, “the idea of a woman travelling alone is so completely outside the experience and beyond the imagination of everyone.”

The glory of those mountains makes one feel that it must all be a dream. Every peak and slope and outcrop is different in shape, texture and colour, the rock and shale and clay shaded purple, rose, green, ochre, black, pale grey, dark grey, brown, navy and off-white. Then, below those arid, soaring cliffs… graceful with willows and poplars, and soft with new grass and filled with bird-song and the rush of the river.

Me: “When you’re on a cycle instead of in a jeep it doesn’t feel like a frying-pan. Moreover, if you look around you you’ll notice that the landscape compensates for the admittedly deplorable state of the road. In fact I enjoy cycling through this sort of country – but thank you for the kind offer. Goodbye.”

American: “Are you a nut-case or what? Gimme that bike and I’ll stick it on behind and you get in here and we’ll get out of this goddam frying-pan as fast as we can. This track isn’t fit for a camel!”

I could go on — Full Tilt is one of those rare books, a handful in a lifetime if one is lucky, brimming with so many touching human moments and such astonishments of natural beauty that one cannot help but have more passages underlined than not. Read it — your life will thank you for it — then revisit composer Paola Prestini’s choral masterwork celebrating the history of the bicycle as an instrument of emancipation and Maria Ward’s nineteenth-century manifesto for bicycling, featuring photographs by her visionary friend and lover Alice Austen, who paved the way for women like Dervla Murphy.

Fortunately, the victim of my machinations was an upholder of Free Enterprise and the Liberty of the Individual. He looked at me in silence for a moment, then said, “Well, I suppose if visas had been required in 1492, the New World would not have been discovered. All right — I’ll play ball. But remember that all this is very unofficial and unbecoming to my position and I’m depending on you to come out alive at the other end, for my sake – which I somehow think you will do.”

Behind us, almost overhanging the mess buildings, rose a 9,000-foot mountain wall of stark, grey rock which was repeated on the other side of the narrow valley; it’s this confinement which keeps the temperature so high despite an altitude of nearly 5,000 feet. Down the valley snow-capped peaks of over 20,000 feet were sharply beautiful against the gentle evening sky and as the setting sun caught the valley walls they changed colour so that their pink and violet glow seemed to illuminate the whole scene.

With an icicle firmly attached to her nose, she makes her way to a Yugoslavian youth hostel, gets blown off her saddle by the most ferocious wind she has ever experienced, tumbles down a fifteen-foot sloping ditch and into a stream frozen so solid that her impact produces not even a crack on the ice, crawls back onto the bicycle, eventually accepts a nightmarish ride in a rickety truck across “250 miles of frozen plain which stretched with relentless white anonymity,” and resumes on two wheels after the truck crashes into a tree. All along, she slakes her soul on the austere beauty of the landscape:

American: “What the hell are you doing on this goddam road?”

By now the thunder had ceased and when the wind dropped the overwhelming silence of the mountains reminded me of the hush felt in a great empty Gothic cathedral at dusk — a silence which is beautiful in itself.

The predominant colour here is blue of all shades, with yellow, black, pink, brown, green and orange tiles blended so skilfully that from a certain distance a façade or minaret looks as though made of some magic precious metal for the colour of which there is no name.

And yet, through the flat tires, the broken rib, the “extreme hunger than extreme thirst, which almost drives one mad,” the food poisoning, the pain of “mental loneliness,” the storms of ice and dust, the fingers burned on the metal handlebars while cycling through unbearable heat at 7,000 feet elevation, “the terrifying dehydration of mouth and nostrils and eyes until… a sort of staring blindness came on,” she never loses sight of why she has endeavored to do this in the first place — why she has obeyed the clarion call of wakefulness to life. In an entry emblematic of the spirit in which she has undertaken her journey, she writes: