They are science.

They are war paint on humanity’s countenance as we combat our great eternal enemy: the mosquito.

But Carson’s most visionary proposition, decades ahead of science, was the development of biological controls that would curtail the reproduction of a particular species without harming other organisms. In consonance with her vision, the City of New York uses larvicide that relies not on toxic chemicals to vanquish mosquito larvae but on rod-shaped aerobic bacteria commonly found in soil. Bacillus sphaericus and Bacillus thuringiensis produce proteins toxic to mosquitos and harmless to mammals, for we lack the enzymes to activate and digest them. But when a mosquito larva ingests the bacterium, the protein in it catalyzes the release of a digestive enzyme in the larva’s gut that binds to a particular receptor, causing mortal damage to the cell membranes.

I noticed them first in my neighborhood — dots of paint hovering over the grate of the storm drain in a blue-green spectrum punctuated by white. I noticed them probably because I had been writing about the wondrous science of the color blue and my brain had formed, as brains tend to, a search image for its present preoccupation.

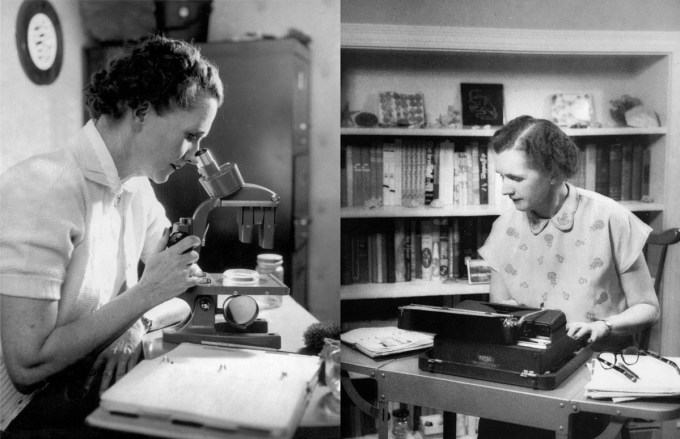

Having devoted two hundred pages of Figuring to Rachel Carson and her epoch-making exposé of the assault on the natural world with DDT — an act of courage and resistance she paid for dearly, not living to see it awaken humanity’s ecological conscience, lead to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, and catalyze the modern environmental movement — I was naturally keen to find out what substances the city uses to attack those curbside mosquito mansions.

Because this entire drama of life and death unfolds in the catch basin beneath the drain grate, both the dead larvae and the bacteria never enter the human world overground — they vanish into the ductile catacombs of the city sewer system to land at the local waste treatment plant along with all the other sewer-stuff, leaving only the colorful expressionist markings on the drain as notation of this silent symphony of science.

And then I started seeing them all over Brooklyn: Red Hook, Greenpoint, even the alleys of the Green-Wood Cemetery — quiet ecstasies of color amid the bleak grey-brown of winter, chromatic macaw cries in the concrete jungle, the ghost of Alma Thomas risen from the dead through the New York City sewer system.

With some stubborn sleuthing through various city agency logs, street art blogs, conspiracy theory fora, and health department reports, I discovered that they are not surreptitious art.

Mosquitos have always plagued cities, but when the deadly West Nile virus arrived in America in 1999, landing in Queens, cities grew serious about defense. The expressionist markings indicate catch basins where the war has been waged. Modeled on the inspired pedal-powered program the City of San Francisco pioneered in 2005, the colorful dots across Brooklyn signal the particular treatment applied to that drain, with each color corresponding to one of the larvicides administered by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. (Yes, that is its name — a curious poetic inversion of the more expected syntax “department of hygiene and mental health.”)

When it rains, when the city washes the streets, water rushes into the drain along with all the debris it carries. To prevent downstream clogging, a catch basin resides just beneath the metal grate to sieve the debris before releasing the water into the drainage pipe. Mosquitos love nesting in these cozy, soggy chambers, where the air is warm enough for the females to survive the winter and where the water doesn’t freeze, so that their eggs — around 200 laid by each female mosquito — can float freely while preparing to become a bloodthirsty army that goes on replicating the 1:200 reproductive ratio ad infinitum.

When Carson published Silent Spring, the ruthless forces she had unmasked — the 0 million chemical pesticide industry, the corporate interests of Big Agriculture, and a complicit government bankrolled by them — set out to tear down this scientist of uncommon courage and competence. Their commonest line of attack, launched everywhere from the pages of Monsanto Magazine to any national station that would give them share of voice, was based on a deliberate misconstrual of the book: Employing the classic tactic of the opinion-manipulator — refuting arguments the opponent hasn’t actually made — they disregarded Carson’s explicit caveat that there are certain lifesaving uses of chemical controls in typhoid and malaria outbreaks, accusing her of advocating for a total ban on pesticides that would cost countless human lives to malaria. Some warped the facts of biochemistry so egregiously that they called her work antiscientific. The grave irony is that Carson opposed not science but the most unscientific stance there is: the arrogance of false certitude unsupported by evidence and the dangerous delusion of pretending to have answers we don’t actually have — an arrogance radiating from the indiscriminate use of DDT, with which the government was hosing down acres of forests and which agricultural airplanes were raining down upon children lunching in the schoolyard amid cornfields.

At first I took them for mindless spray-can tests by a street artist getting ready to graffiti a nearby wall. But no surface in sight was emblazoned with these colors.