In consonance with her famous assertion that “love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real” — a realization that is both the basis of morality and the motive force of science — she adds:

The same virtues, in the end the same virtue (love), are required throughout, and fantasy (self) can prevent us from seeing a blade of grass just as it can prevent us from seeing another person. An increasing awareness of “goods” and the attempt (usually only partially successful) to attend to them purely, without self, brings with it an increasing awareness of the unity and interdependence of the moral world. One-seeking intelligence is the image of ‘faith’. Consider what it is like to increase one’s understanding of a great work of art.

Shining the sunbeam of her own intellect on Plato’s blind spot to reveal the deepest meaning of morality, she writes:

Beholding beauty in nature and in art, Murdoch argues, can serve as a sort of sacrament for the spirit — the experience provides (in one of her loveliest phrases, and one of the loveliest concepts ever committed to words) “an occasion for unselfing.” But this experience, she cautions, is not easily extended into matters of people and actions — the matters morality aims to negotiate — “since clarity of thought and purity of attention become harder and more ambiguous when the object of attention is something moral. With an eye to Plato and his conception of beauty as the visible dimension of goodness, which is inherently invisible, she writes:

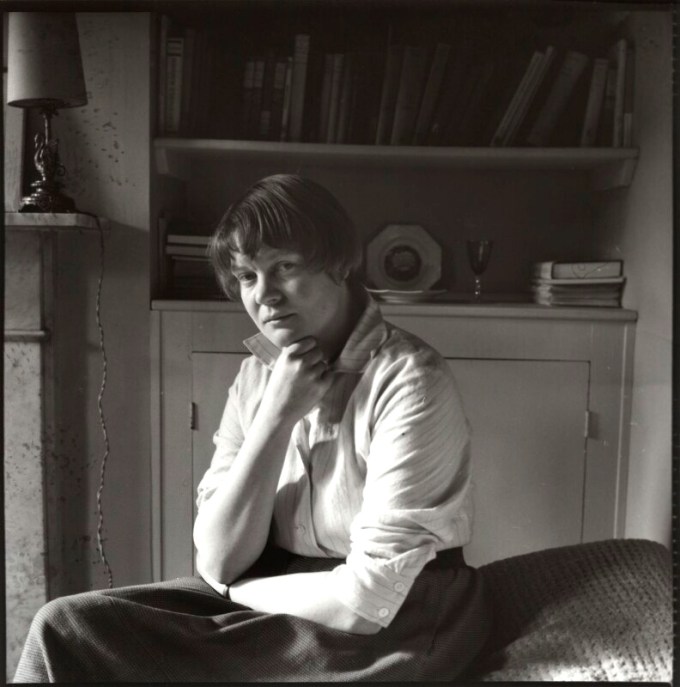

The dazzling-minded Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) took up these questions in her play Above the Gods — one of two Platonic dialogues she wrote in the 1980s, later included in the posthumous Murdoch anthology Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library), which remains one of the finest works of writing and thinking I have encountered.

What it takes, she suggests, is “something analogous to prayer, though it is something difficult to describe, and which the higher subtleties of the self can often falsify” — not some “quasi-religious meditative technique,” but “something which belongs to the moral life of the ordinary person.” Half a century after the existentialist and mystic Simone Weil liberated this raw mindfulness from the strict captivity of religion with her lovely observation that “attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer,” for it “presupposes faith and love,” Murdoch writes:

In the world of science, we endeavor to uncover fundamental laws and elemental truths indifferent to our opinions of them — those selfsame truths and laws that made us and govern the electrical impulses coursing through our cortices at 100 meters per second to forge the thought-patterns of opinion. But in the human world where we live, we swirl in the movable host of human relations and rationalizations, vaguely aware that there is no universal truth and therefore no universal good, because every utopia is built on some else’s back. We devise frameworks for righting our relations, which we call morality, but in our helpless confusion about what goodness is, we too readily mistake certainty for truth and self-righteousness for truth, then lash one another with our certitudes and rightneousnesses, mistaking the lashing for the light of morality.

When our species was younger and more frightened of reality, myths and religions have provided the comfort of easy causalities and easy moralities to salve the confusions of complexity. But as the epoch of scientific discovery began disproving some of those sacred certainties — first ejecting us from the placid plane of the flat Earth, then from our self-soothing centrality in the Solar System, then from our grandiose exceptionalism in the order of living things, then from our galactic exceptionalism — the moral certitudes about goodness also came unloosed, for they too were built upon the same self-righteous foundation as the old delusions about the geometry of the universe and the immutability of life-forms.

Religion isn’t just a feeling, it isn’t just a hypothesis, it’s not like something we happen not to know, a God who might perhaps be there isn’t a God, it’s got to be necessary, it’s got to be certain, it’s got to be proved by the whole of life, it’s got to be the magnetic centre of everything.

And yet this more-than-feeling aims at something beyond religion, beyond even explicit knowledge, at the center of which is the idea — the existence — of goodness:

Set in Athens in the late fifth century B.C. and structured as a conversation between a sixty-something Socrates, a twenty-something Plato, and four fictional Greek youths, the dialogue tussles with the question of whether the age of science has knelled the death toll of religion and, if so, where this leaves our search for truth and our longing for goodness — that elemental hunger for the ultimate meaning of reality, for our responsibility to reality.

In a way, goodness and truth seem to come out of the depths of the soul, and when we really know something we feel we’ve always known it. Yet also it’s terribly distant, farther than any star… beyond the world, not in the clouds or in heaven, but a light that shows the world, this world, as it really is… In spite of all wickedness, and in all misery, we are certain that there really is goodness and that it matters absolutely.

When Nietzsche weighed our human notion of truth, he regarded it as “a movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished.” This is true of truth in the human world, and this is where science and society differ. The disparity is the reason why the scientific perspective can offer such gladsome calibration and consolation for our human struggles.

Of course Good doesn’t exist like chairs and tables, it’s not… either outside or inside. It’s in our whole way of living, it’s fundamental like truth. If we have the idea of value we necessarily have the idea of perfection as something real… People know that good is real and absolute, not optional and relative, all their life proves it. And when they choose false goods they really know they’re false. We can think everything else away out of life, but not value, that’s in the very ground of things.

The idea of contemplation is hard to understand and maintain in a world increasingly without sacraments and ritual and in which philosophy has (in many respects rightly) destroyed the old substantial conception of the self. A sacrament provides an external visible place for an internal invisible act of the spirit.

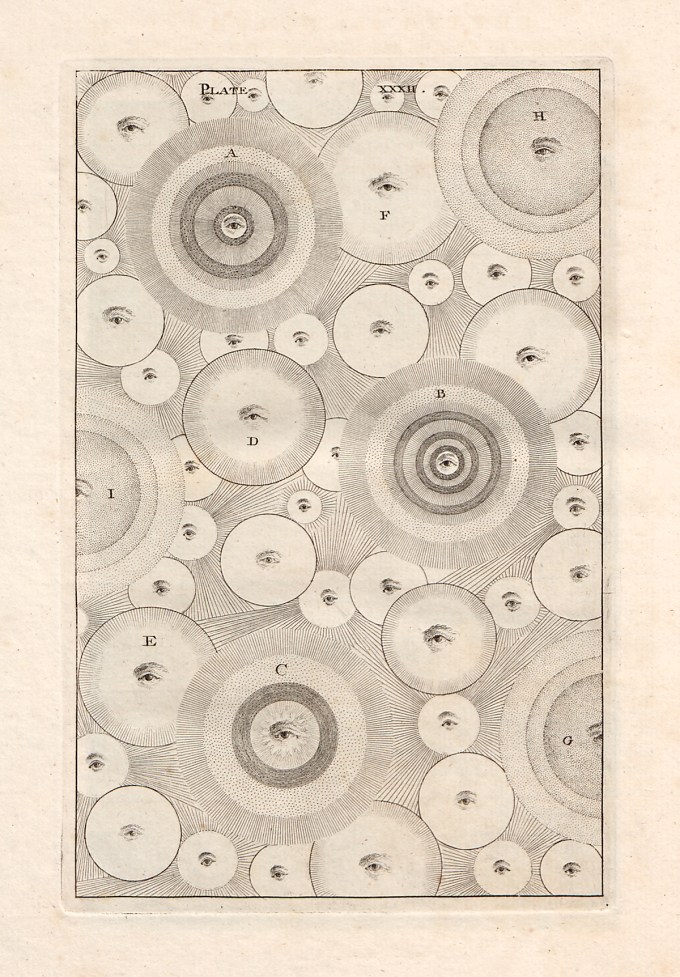

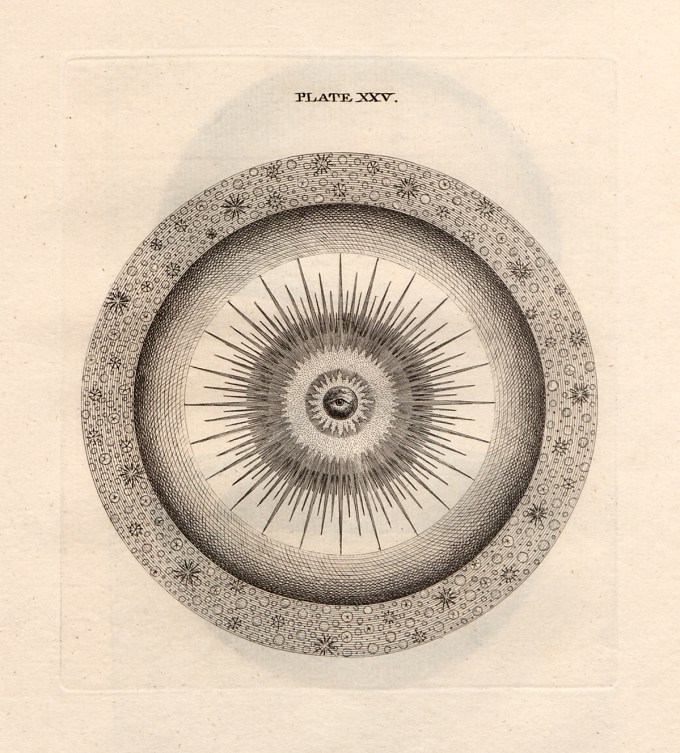

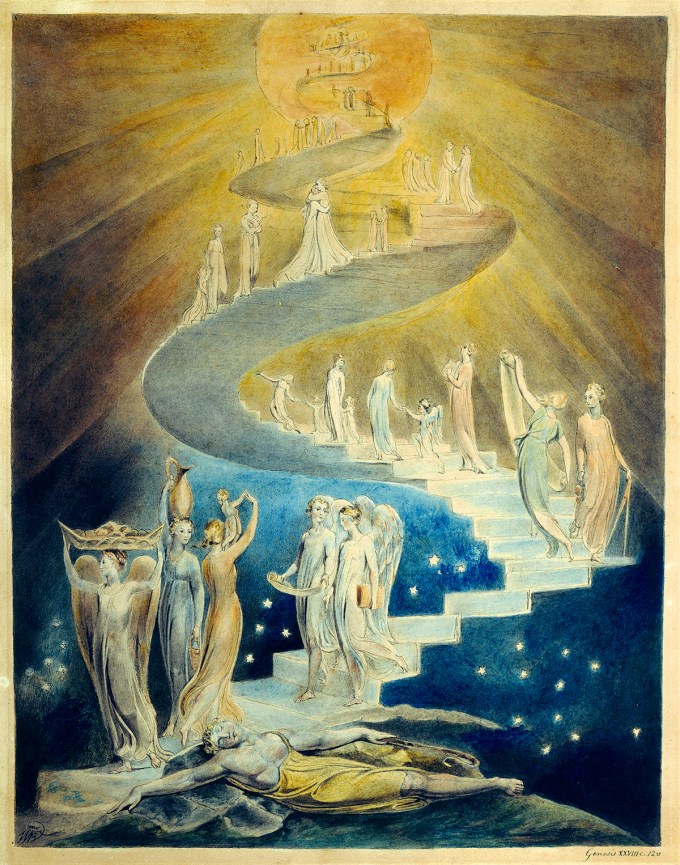

Plato pictured the good man as eventually able to look at the sun. I have never been sure what to make of this part of the myth. While it seems proper to represent the Good as a centre or focus of attention, yet it cannot quite be thought of as a “visible” one in that it cannot be experienced or represented or defined. We can certainly know more or less where the sun is; it is not so easy to imagine what it would be like to look at it. Perhaps indeed only the good man knows what this is like; or perhaps to look at the sun is to be gloriously dazzled and to see nothing. What does seem to make perfect sense in the Platonic myth is the idea of the Good as the source of light which reveals to us all things as they really are. All just vision, even in the strictest problems of the intellect, and a fortiori when suffering or wickedness have to be perceived, is a moral matter.

It is here that it seems to me to be important to retain the idea of Good as a central point of reflection, and here too we may see the significance of its indefinable and non-representable character. Good, not will, is transcendent. Will is the natural energy of the psyche which is sometimes employable for a worthy purpose. Good is the focus of attention when an intent to be virtuous co-exists (as perhaps it almost always does) with some unclarity of vision.

The question of goodness permeates Murdoch’s entire body of work, but she plumbs this particular aspect of it — its bearing on truth and morality, lensed through Plato — in greater depth in an essay titled On “God” and “Good,” also included in Existentialists and Mystics. With an eye to the relationship between the good and “the real which is the proper object of love, and of knowledge which is freedom,” she considers what it takes for us to purify our attention in order to take in reality on its own terms, unalloyed with our attachments and ideas.

She invokes Plato’s famous allegory of the cave — humanity’s first great thought experiment about the nature of consciousness and its blind spots, in which the prisoners of unreality mistake the flickering shadows cast by the fire on the cave wall for the light of reality; but then, once set free by goodness and knowledge (and here is another exquisite formulation of Murdoch’s) “the moral pilgrim emerges from the cave and begins to see the real world in the light of the sun, and last of all is able to look at the sun itself.”

Complement these fragments from the wholly indispensable Existentialists and Mystics — which also gave us Murdoch on what love really means, art as a force of resistance, and the key to great storytelling — with philosopher Martha Nussbaum (who, is in many ways, Murdoch’s intellectual heir) on what it means to be a good human being and physicist Alan Lightman on our search for the meaning beyond reality’s truths.

When Murdoch’s Socrates observes that a distinction between religion and morality is yet to be made, without which the central question of reality and truth cannot be answered, an impassioned Plato responds:

Goodness, in Murdoch’s lovely conception, emerges as both object and background, both knower and known. This renders moot the objectifying question, voiced by one of Plato’s sparring partners — a young Sophist — of where goodness resides in relation to reality: either outside us, existing in something like a god, or within us, as an internal image we refer to. Observing that it is both inside and outside, Murdoch’s Plato responds: