Few artists have accomplished this more effectively and enchantingly than Étienne Denisse (1785–1861).

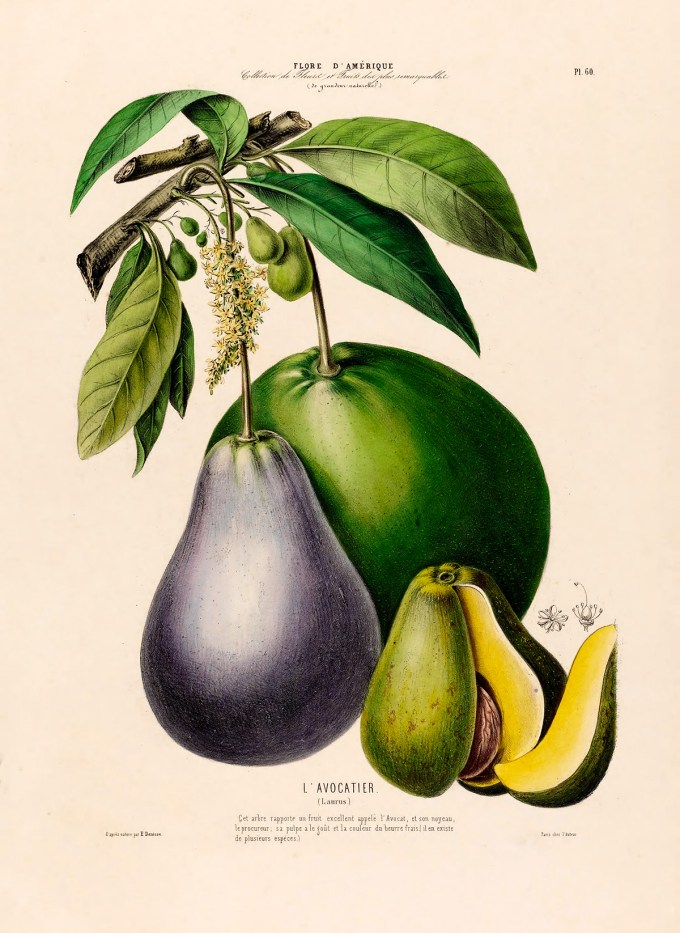

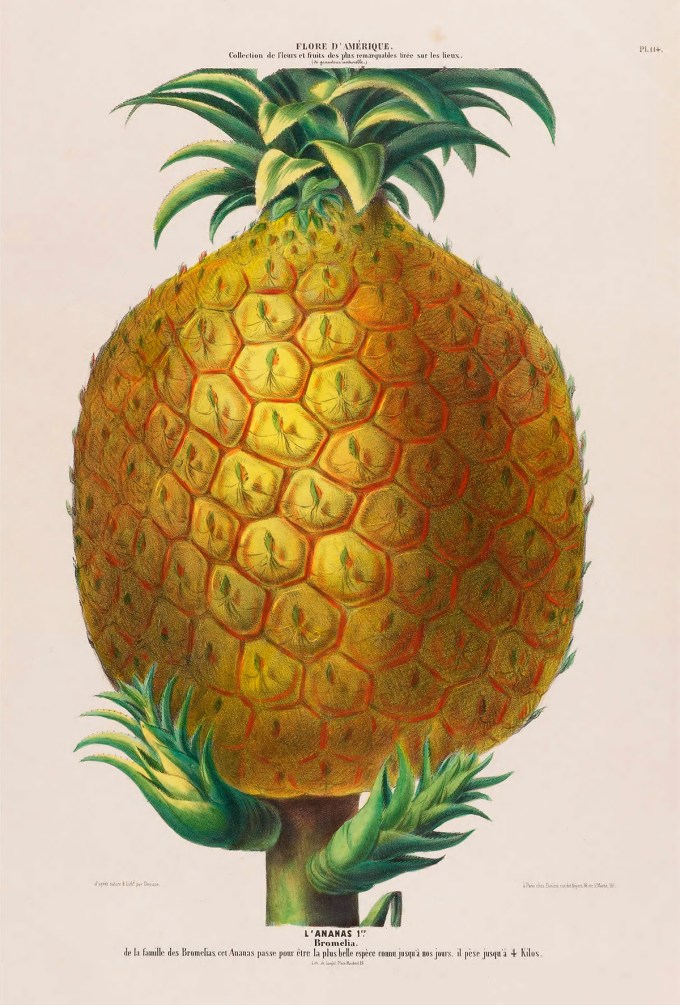

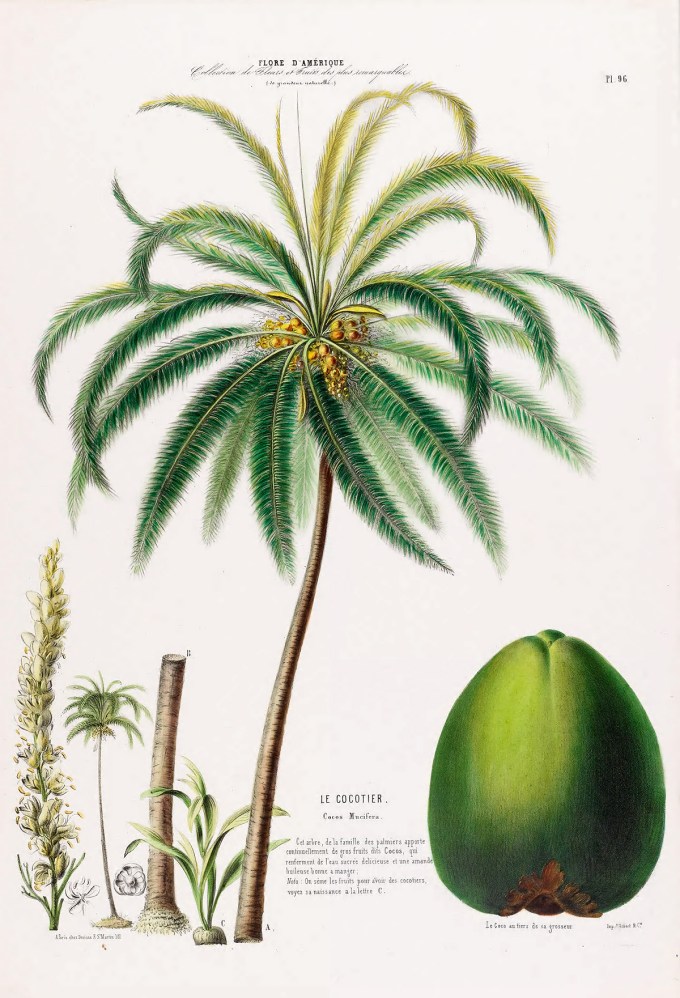

There are plants that are now fixtures of the global palate — the banana, mango, pineapple, cacao, coffee, coconut, various citrus fruit, and the avocado, that gladsome ghost of evolution.

To put our familiar lives in perspective and jolt us awake to the wonder of so much we have come to take for granted, let us picture this:

It is the 1840s and you, like most of humanity, have never traveled more than a few miles beyond where you were born, have never met a person native to a different country, have never seen a bird native to a different continent or a flower native to a different climate. Like most of humanity, you never will. Photography has just been born, too costly and cumbersome a technology to carry into the world, much less to carry the world to you. If you have had the privilege of setting foot in a library — that is, if you were born with a Y chromosome and very little melanin — you might have leafed through a heavy leather-bound encyclopedia or an herbarium and marveled at life-forms from faraway lands. If you are among the slender portion of our species lucky enough to live near one of the world’s handful of natural history museums and botanical gardens, you might have glimpsed some specimens of exotic plants.

Before science made the technologies of image-capture and global travel possible, botanical and natural history illustrators were singular civil servants — artists in the service of their subjects, tasked with capturing and conveying what it is like to be a particular plant or animal living in a particular habitat. Here, each exquisitely rendered specimen seems to say to its remote viewer, aren’t I strange and beautiful and worthy of inclusion in the family of life?

Complement with Denisse’s compatriot and contemporary Charles Antoine Lemaire’s astonishing illustrations of cacti and the trailblazing 18th-century artist Sarah Stone’s natural history paintings of exotic, endangered, and extinct species, then revisit the heartening story of how two 19th-century teenage sisters fomented one of the greatest triumphs of modern conservation with their forgotten paintings of Australian butterflies.

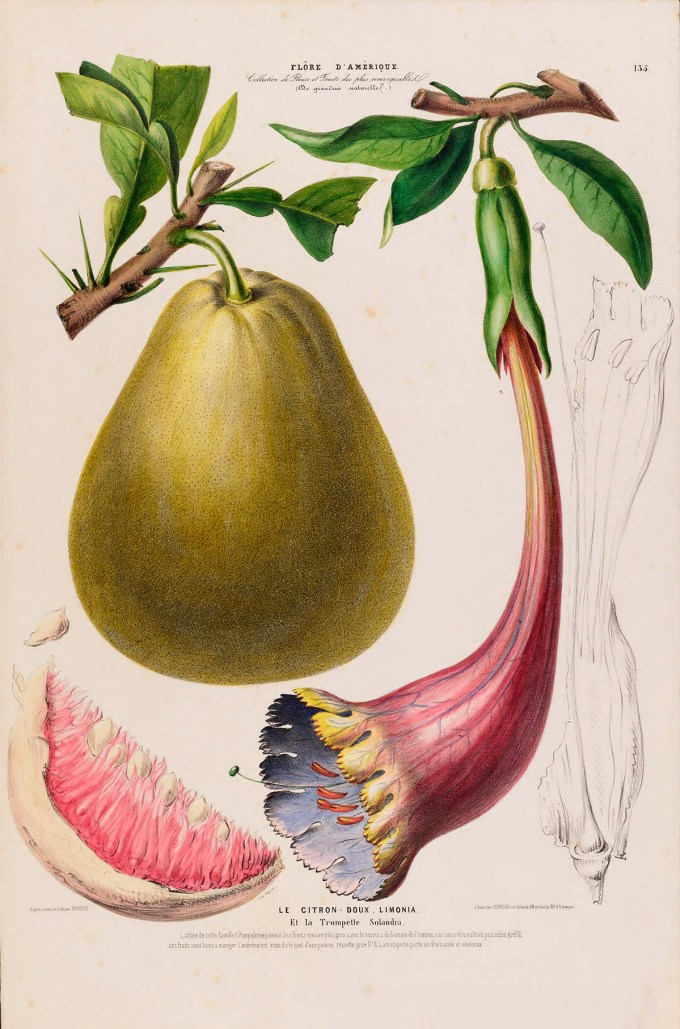

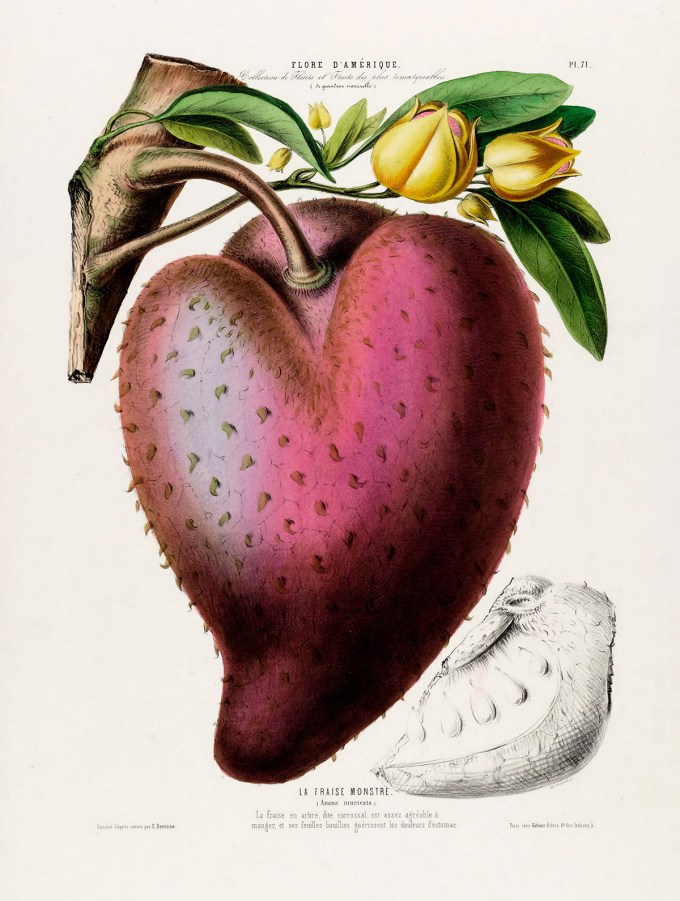

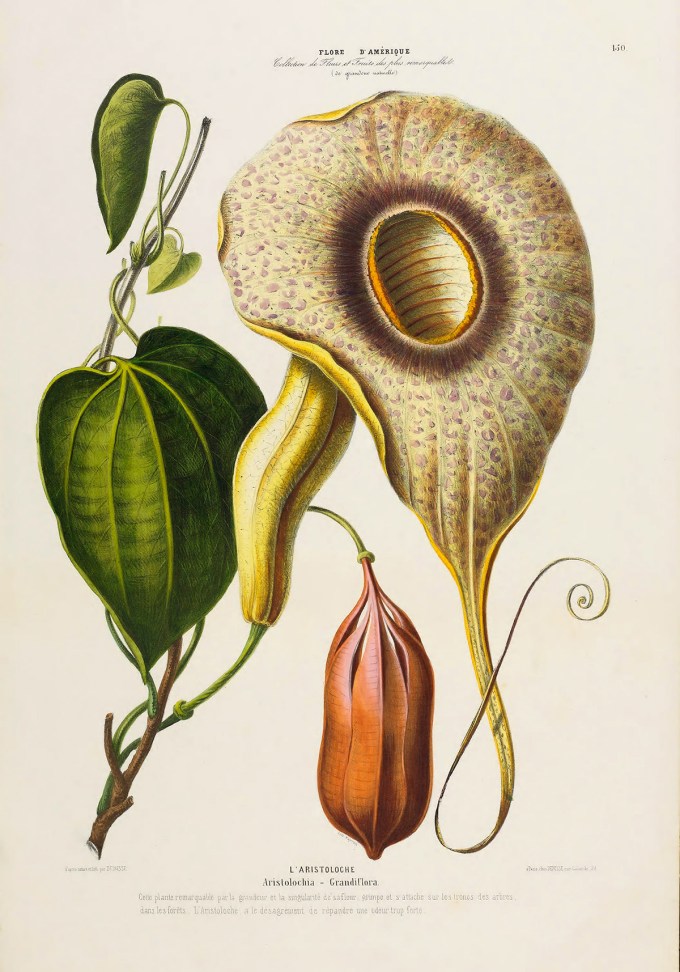

As a young artist at the botanical garden of the natural history museum in Paris, Denisse had attracted the attention of the crown with his uncommonly detailed and scrumptious paintings of plants. He was eventually hired as lithographer for the French royal court, then dispatched to the French Caribbean territories, where he spent many years collecting and studying plants completely novel to European eyes, periodically sending his illustrations back to France. Between 1843 and 1846, two hundred and one astonishing hand-colored lithographic plates based on Denisse’s drawings from life were published as Flore d’Amérique. One of the very few surviving copies has been painstakingly restored and digitized by the wonderland that is the LuEsther T. Mertz Library of the New York Botanical Garden in collaboration with the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

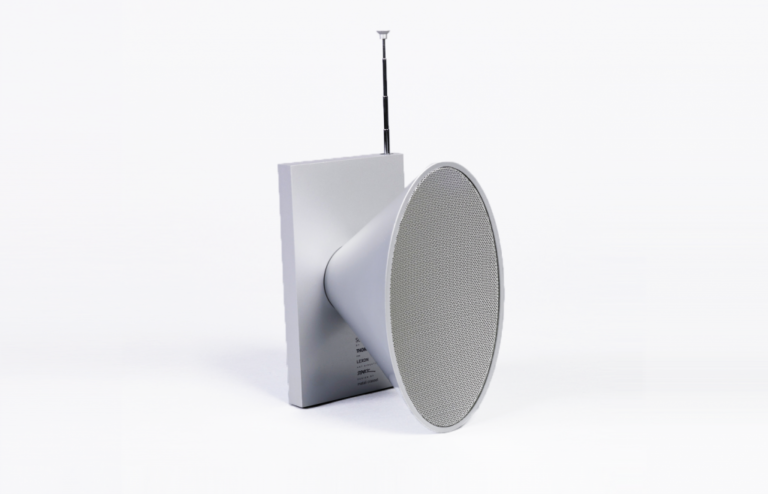

There are plants still exotic to non-native eyes: wondrous cacti; strange plums; the blue flame of the Mexican verbena; the enticing evergreen flowering Tillandsia, which Denisse dubbed “the immortal Creole,” now teetering on the brink of ecological mortality; the scaly chirimuya fruit beloved by the Incas; the colossal thorned heart of its cousin the soursop, which I still remember first encountering in Kauai with gaping disbelief at the otherworldly life-forms of which this planet is capable; the mammoth gramophone blossom of the pelican flower, Aristolochia grandiflora — one of Earth’s largest flowers, with a scent of rotting flesh to attract flies as pollinators; the Averrhoa with its luscious striped fruit reminiscent of a mosque top, named after the 12th-century Islamic astronomer and philosopher Averroes.

Denisse did for the plants of the Americas what the Dutch engraver Louis Renard had done for the psychedelic fishes of the South Seas a century earlier and what the English marine biologist William Saville Kent would do for the corals of the Great Barrier Reef a generation later. Epochs before our digital voyeurism, before photo albums and air travel, his vibrant illustrations of unseen and unimaginable living wonders became the era’s National Geographic footage and Instagram feeds rolled into one.

But you are you — whatever degree of privilege chance has conferred upon you at birth, you are curious and you hunger for beauty, enraptured by the artwork that is your only portal to the living wonders of this world.

Denisse seems to have had a special fondness for Earth’s very few true blues. Blue-flowering plants, so rare in nature, occupy a sizable portion of his folios — among them the unexpected blossoms of the mahogany tree and the startling butterfly pea with its intensely colored cobalt flowers and their perfect bright-yellow folds that earned the plant the Latin name Clitoria.

There is the tender-tongued hibiscus with its exultant petals, believed to cure snakebite; the passionflower with its spectacle of geometry and flower, whose fruit Denisse found “quite good to eat”; the otherworldly epidendrum orchid, which Denisse calls “the butterfly of plants”; the buxom wild squash of the Carolinas.

Some plants, familiar to the tongue, are a startlement to the eye in their native form — the furry paw of the yam, the carnival carousel crown of the papaya tree, the surprising pink morning-glory blossoms of the sweet potato, the upside-down fleshy heart of the cashew’s fruiting body.