We do this on the personal level — out of such selective memory and by such exquisite exclusion, we compose the narrative that is the psychological pillar of our identity. We do it on the cultural level — what we call history is a collective selective memory that excludes far more of the past’s realities than it includes. Borges captured this with his characteristic poetic-philosophical precision when he observed that “we are our memory… that chimerical museum of shifting shapes, that pile of broken mirrors.” To be aware of memory’s chimera is to recognize the slippery, shape-shifting nature of even those truths we think we are grasping most firmly.

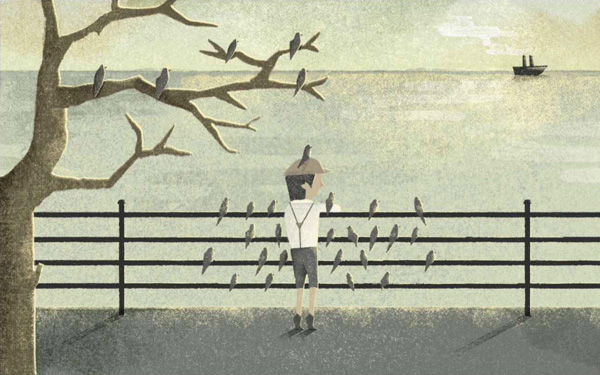

As researchers in the second half of the twentieth century came to shed light on the foibles of memory, Kurosawa’s masterpiece lent its name to the amply documented unreliability of eyewitness accounts. The Rashomon effect, detailed in this wonderful animated primer from TED-Ed, casts a haunting broader nimbus of doubt over our basic grasp of reality — we only exist, after all, as eyewitnesses of our own lives.

Nearly a century after Nietzsche admonished that what we call truth is “a movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms… a sum of human relations which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished,” the great Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa (March 23, 1910–September 6, 1998) created an exquisite cinematic metaphor for the slippery memory-mediated nature of truth in his 1950 film Rashomon, based on Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story “In a Grove” — a psychological-philosophical thriller about the murder of a samurai and its four witnesses, who each recount a radically different reality, each equally believable, thus undermining our most elemental trust in truth.

All of these psychological perplexities arise from the basic neurophysiological infrastructure of how memories form and falter in the brain — something the great neurologist Oliver Sacks explored in his classic medical poetics of memory disorders, and something South African biomedical scientist Catharine Young explores in another TED-Ed episode, animated by the prolific Patrick Smith:

It is already disorienting enough to accept that our attention only absorbs a fraction of the events and phenomena unfolding within and around us at any given moment. Now consider that our memory only retains a fraction of what we have attended to in moments past. In the act of recollection, we take these fragments of fragments and try to reconstruct from them a totality of a remembered reality, playing out in the theater of the mind — a stage on which, as neuroscientist Antonio Damasio has observed in his landmark work on consciousness, we often “use our minds not to discover facts, but to hide them.”

Complement with Neurocomic — a graphic novel about how the mind works — and the animated science of how playing music benefits your brain more than any other activity, then revisit Virginia Woolf on how memory seams our lives, Sally Mann on how photographs can unseam memory, and neuroscientist Suzanne Corkin on how medicine’s most famous amnesiac illuminates the wonders of consciousness.

[embedded content]

[embedded content]