“We hear and apprehend only what we already half know,” Thoreau wrote as he considered what it takes to see unblinded by preconception. “The art of seeing has to be learned,” Marguerite Duras sang a century later from the pages of her symphonic reckoning with what makes life worth living.

The habit of observation is the habit of clear and decisive gazing. Not by a first casual glance, but by a steady deliberate aim of the eye are the rare and characteristic things discovered. You must look intently and hold your eye firmly to the spot, to see more than do the rank and file of mankind.

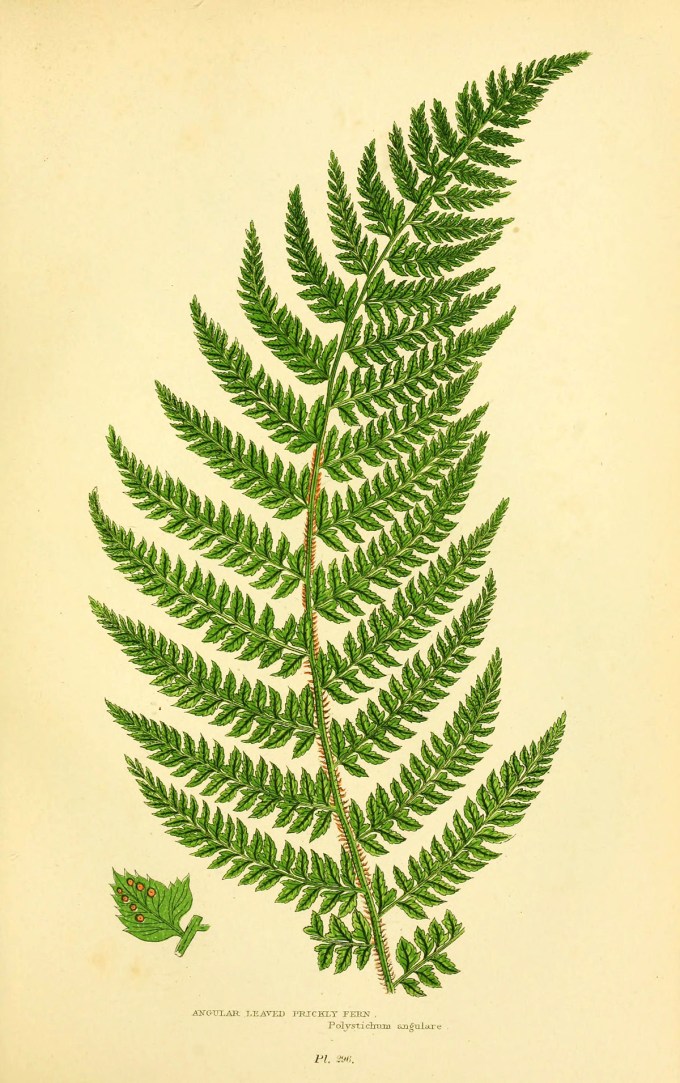

This is just as necessary to the naturalist as to the artist or the poet. The sharp eye notes specific points and differences, — it seizes upon and preserves the individuality of the thing.

Noting how one eye seconds and reinforces the other, I have often amused myself by wondering what the effect would be if one could go on opening eye after eye to the number say of a dozen or more. What would he see? Perhaps not the invisible — not the odours of flowers nor the fever germs in the air — not the infinitely small of the microscope nor the infinitely distant of the telescope. This would require, not more eyes so much as an eye constructed with more and different lenses; but would he not see with augmented power within the natural limits of vision? At any rate some persons seem to have opened more eyes than others, they see with such force and distinctness; their vision penetrates the tangle and obscurity where that of others fails like a spent or impotent bullet.

He observes that uncommon seers like Thoreau and Audubon — uncommon seers like himself, we can safely say with posterity’s clarity of hindsight — always seem to have more than two eyes open: “not outward eyes, but inward.” He writes:

We open another eye whenever we see beyond the first general features or outlines of things — whenever we grasp the special details and characteristic markings that this mask covers.

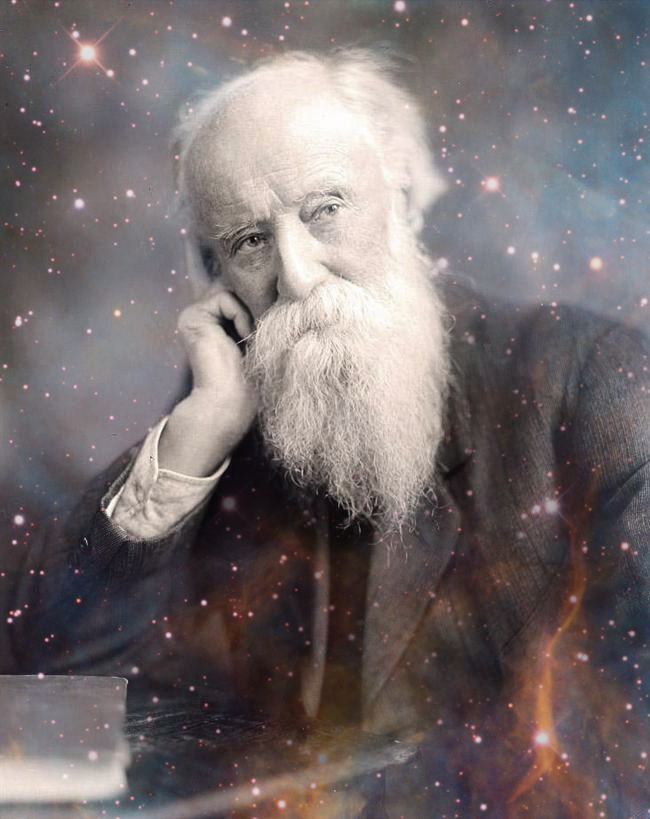

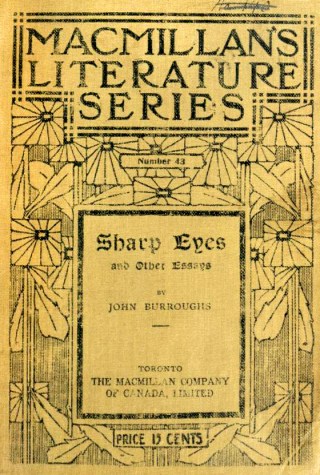

Partway in time between these two uncommon seers, another — the great naturalist (or “naturist,” as he described himself) John Burroughs (April 3, 1837–March 29, 1921) took up the subject in the title essay of Sharp Eyes and Other Essays (public library | free ebook), published in the final years of his long and lush life.

In a delightful take on the notion of seeing with new eyes, Burroughs considers what it means to be a seer — a person of uncommon vision into the realms of reality to which we spend our ordinary days blind, but which are always there for the seeing if we know how to look:

[…]

We think we have looked at a thing sharply until we are asked for its specific features. I thought I knew exactly the form of the leaf of the tulip-tree, until one day a lady asked me to draw the outline of one… Most of the facts of Nature, especially in the life of the birds and animals, are well screened. We do not see the play because we do not look intently enough.

An epoch before Susan Sontag held up as the writer’s primary task and talent that of being “a professional observer,” Burroughs adds:

In a sentiment the poetic physicist Richard Feynman would echo a generation later in his wonderful ode to a flower, Burroughs notes that “science confers new powers of vision” by revealing new layers and details of nature “as if new and keener eyes were added.” It is a power we can train in our ordinary way of seeing, just by changing how we look: