Could we trace the mental history of our great naturalists, we should find that many who have devoted their lives to the pursuits of science, had at first their attention directed to it, like Linnaeus, by listening to a conversation, or, like Sir Joseph Banks, by musing, in a leisure moment, on the beauty of a flower; and thus the reading of a little volume like this, on common things, may serve to awaken an interest in nature, which shall not sleep again.

Having secured financial independence by her own talent and devotion, she never had to marry out of need, as most women of her epoch did. And so she married out of love, at sixty.

When is it, exactly, the turning point when life could have gone one way or another?

“We call it ‘Nature’; only reluctantly admitting ourselves to be ‘Nature’ too,” Denise Levertov wrote in her stunning poem “Sojourns in the Parallel World.”

She kept going: painting and writing, punctuating the natural history with poetry. Every couple of years, she released a new scrumptiously illustrated book.

Published in 1791, Erasmus Darwin’s wildly popular book was deemed too explicit for unmarried women to read. But they did read it. Many took up botany. Some who were artistically gifted brought their gift to the new science.

When exactly the split happened is difficult to discern — this crossing-point at which human nature reached upward to its higher potential and downward to its darkest depths at the same time; this divide into “double consciousness,” to borrow Dr. Du Bois’s enduring term for another kind of damaging otherizing the human animal has perpetrated.

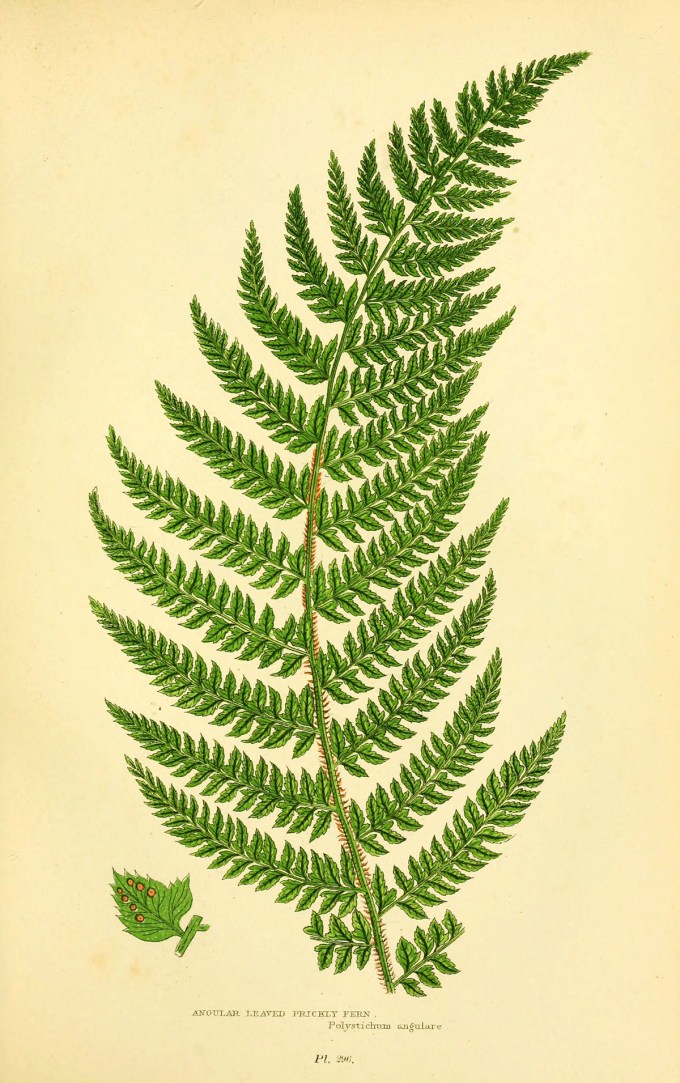

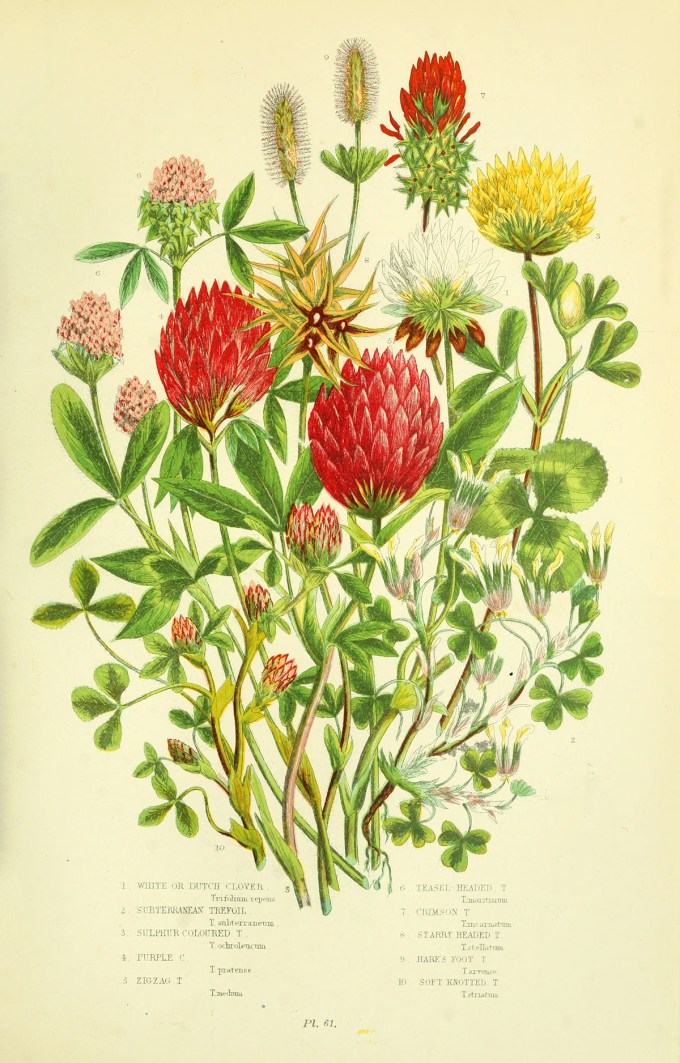

From across the centuries, these time-yellowed plates whisper their quiet, stubborn insistence that we are Nature, too.

But to me, something of the warm human hand that painted them remains in them, something radiating the passionate attention with which this middle-aged Victorian woman brought to millions of people, against all the odds of her time and body, the intimate realities of nature as she saw them with her own bygone eyes.

But it might have happened even sooner, had the science of botany and its beguiling art not cast upon our species a new enchantment with the wonder of the living world.

Her books were portable awakenings, extending a ravishing invitation to paying attention — that elementary particle of wonder that shimmers in every excellent scientist and every excellent soul.

When a family friend introduced her to botany, a new world of possibility burst open — she devoted herself to studying the science of the living world and perfecting her art.

At thirty-three, she made her tentative debut — no small feat for a woman in Victorian publishing — with a book titled The Field, the Garden, and the Woodland. It was quietly received, but that didn’t matter — she had found her calling, and it fed her, and she fed it back to the world.

While in America Clarissa Munger Badger was inspiring a nation and its greatest poet with her botanical art, Anne Pratt (December 5, 1806–July 27, 1893) was doing the same in England.

It had all begun with a poem: A century before his grandson forever changed our understanding of how nature evolved, the physician, poet, abolitionist, and scientist-predating-the-coinage-of-scientist Erasmus Darwin published The Botanic Garden — a book-length poem that used scientifically accurate metaphors to scintillate the popular imagination with the new science of sexual reproduction in plants. (“It has always pleased me to exalt plants in the scale of organised beings,” Charles Darwin would write in his autobiography a century before Lucille Clifton named the kinship between organized beings in her stunning poem “cutting greens.”)

In poor health since her earliest years, and with a knee disability, Anne grew up almost entirely indoors. Drawing became how she survived the loneliness of childhood, how she brought nature closer to her.

People started taking notice, moved by her passionate approach to botany, her keen understanding that a touch of the poetic does not dilute the scientific but deepens it (as we now know), her psychologically insightful and empathetic decision to go against the scowl of the academy and use the English rather than Latin names of plants, demolishing the wall of intimidation erected between lay people — especially women, who had no access to formal education in science — and the study of nature.

For a little while, only a century or so, beauty seemed to forestall entitlement.

Anne Pratt’s illustrations besotted readers with the beauty of this world and went on to inspire generations of botanists, artists, and ordinary people who hungered for intimacy with nature. By the final year of her century — when she had already returned her atoms to the soil she so cherished, having outlived her era’s life expectancy twofold — her oft-reprinted series was celebrated as “the standard popular work upon British Flora.” Her illustrations continued to be widely beloved — and widely plagiarized — for a century.

When the series first appeared, Anna Atkins had already revolutionized scientific illustration with the world’s first science book illustrated with photographs. But photography was yet to alter our way of seeing and our style of looking, yet to change the history of science, the history of art, and the whole of visual culture with. Still a young technology with a shadow already looming over it, it was cumbersome and prohibitively expensive, weighed down by the slow uptake of all novel ideas. Illustration remained the primary art of science, and in botany it was just reaching its peak.

The closest Anne Pratt came to naming the personal credo that emanated from her books appeared in her preface to her natural history of the seashore, but it could be said of any of her works:

By the time she was in her fifties, Anne Pratt had become one of the most beloved botanical illustrators of the Victorian era. Queen Victoria herself privately relished and publicly praised her work.

Nowhere does this ethos shine more brilliantly than in The Flowering Plants, Grasses, Sedges, and Ferns of Great Britain and Their Allies the Club Mosses, Pepperworts, and Horsetails — her six-volume, two-decade labor of love and knowledge, detailing more than a thousand species with hundreds of exquisite illustrations, which established this late-blooming visionary as one of the greats — the first volume was published in the final year of Anne’s forties, the last a year after she got married.

Complement with 21st-century artist Rosalind Hobley’s haunting cyanotype portraits of flowers, pioneering plant ecologist Edith Clements’s gorgeous early-20th-century paintings of Rocky Mountain wildflowers, French artist Étienne Denisse’s 19th-century illustrations of the most luscious plants of the Americas, and Elizabeth Blackwell’s 18th-century illustrations for the world’s first pictorial encyclopedia of medicinal plants, then revisit Anna Botsford Comstock’s Handbook of Nature Study — the century-old field guide to wonder that laid the foundation of the youth climate action movement.

Today, with every species she painstakingly painted instantly available in trillions of digital photographs depicting its littlest detail from every imaginable angle, the illustrations might appear to some useless — fossils of a bygone epoch from the evolution of seeing.