That is what Nick Cave, part Byron and part Baldwin for our own time, explores in an issue of his Red Hand Files — the online journal in which he takes questions from fans and answers them in miniature essays of uncommon insight, soulfulness, and sensitivity, opening up improbable backdoors into those cavernous chambers where our most private yet common bewilderments about art and life dwell, and filling those chambers with the light of sympathetic understanding.

There are echoes here of Whitman, who declared in his “Laws of Creation” for “strong artists and leaders… and coming musicians” that to create means only to “satisfy the Soul”; there are echoes, too, of Mary Oliver and her invocation of “the third self” — that crucible of our creative energy, which demands of us to give it both power and time.

A century and a poetic revolution after him, Rilke captured this combinatorial nature of creativity when he contemplated what it takes to write anything of beauty and substance.

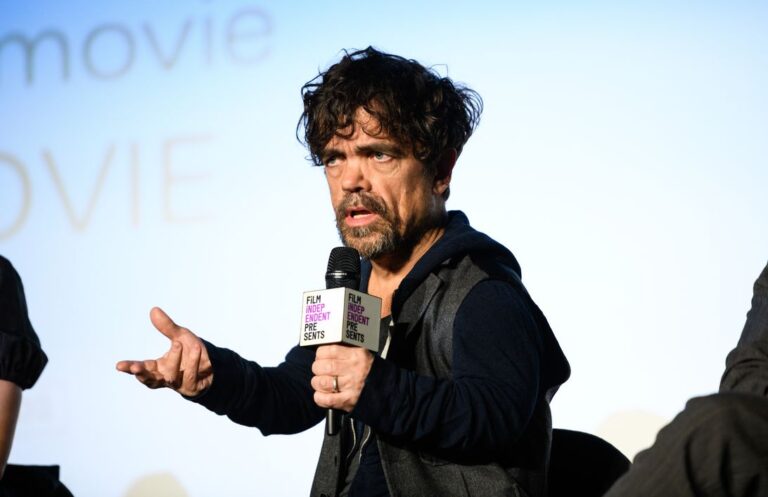

When a fan from my own neighborough asks Cave how he muffles all of his influences in order to hear his own inner voice and trust that he is making something wholly his own, he answers with his characteristic poetics of numinous pragmatism:

Worry less about what you make — that will mostly look after itself, and is to some extent beyond your control, and perhaps even none of your business — and devote yourself to nourishing this animating spirit. Bring all your enthusiasm to bear on the development of that good and essential force. This is done by a commitment to the creative act itself. Each time you tend to that ingenious spark it grows stronger, and sets afire the ordinary gifts of the imagination. The more dedication you show to the process, the better the work, and the greater your gift to the world. Apply yourself fully to the task, let go of the outcome, and your true voice will appear. You’ll see. It can be no other way.

All poets — “poets” in Baldwin’s broad sense of “the only people who know the truth about us,” encompassing all artists, all makers of beauty and knowledge, all shamans of our self-knowledge — understand this intimately, and therefore understand the most elemental truth about creativity: that *these two words are chimeras of the ego.

Complement with Cave on music, feeling, and transcendence in the age of algorithms and grief as a portal to aliveness, then revisit poet Naomi Shihab Nye on the two driving forces of creativity, John Coltrane on outsiderdom as a wellspring of originality, John McPhee on the relationship between originality and self-doubt, and Paul Klee on how an artist is like at tree.

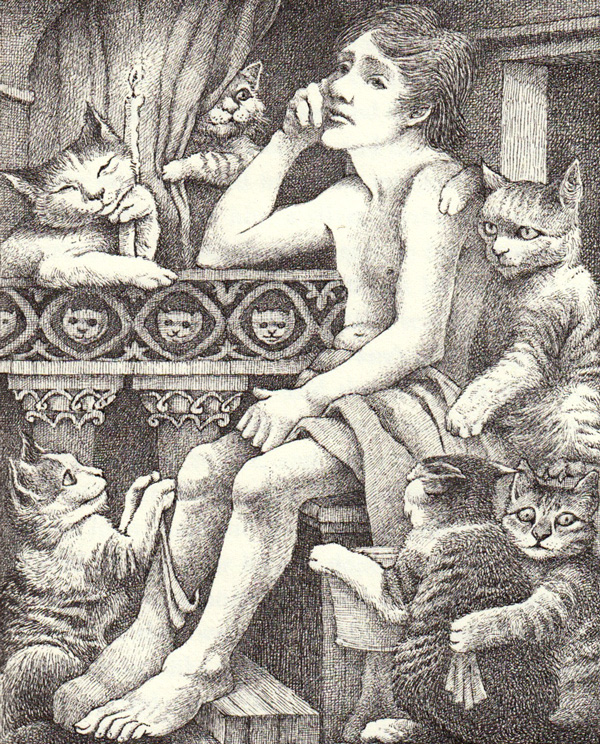

Her father — the poet Lord Byron, rockstar of the Romantics — embodied this in his own work, fusing influences* as diffuse in time, space, and sensibility as Confucius and Virgil, Erasmus Darwin and and Mary Shelley, Greek tragedy and Galilean astronomy, to compose some of the world’s most original* and enduring poetry.

In consonance with Black Mountain College poet and ceramicist M.C. Richards’s lovely notion of creativity as the poetry of our personhood and with anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson’s concept of “composing a life” — which captures with such poetic precision the fundamental fact that our very lives are the ultimate creative work — Cave adds:

Two years before she fused her childhood impression of a mechanical loom with her devotedly honed gift for mathematics to compose the world’s first computer program in a 65-page footnote, Ada Lovelace postulated in a letter that creativity is the art of discovering and combining — the work of an alert imagination that “seizes points in common, between subjects having no very apparent connexion, & hence seldom or never brought into juxtaposition.”

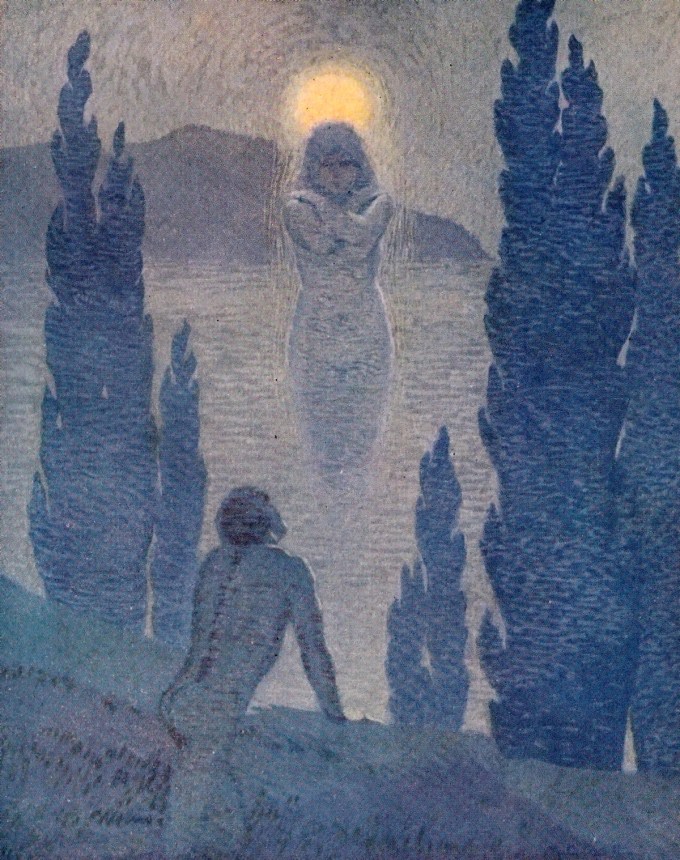

Nothing you create is ultimately your own, yet all of it is you. Your imagination, it seems to me, is mostly an accidental dance between collected memory and influence, and is not intrinsic to you, rather it is a construction that awaits spiritual ignition.

Your spirit is the part of you that is essential. It is separate from the imagination, and belongs only to you. This formless pneuma is the invisible and vital force over which we toss the blanket of our imagination — that habitual mix of received information, of memory, of experience — to give it form and language. In some this vital spirit burns fiercely and in others it is a dim flicker, but it lives in all of us, and can be made stronger through daily devotion to the work at hand.

There is no blank slate upon which works of true originality are composed, no void out of which total novelty is created. Nothing is original because everything is an influence; everything is original because no influence makes its way into our art untransmuted by our imagination. We bring to everything we make everything we have lived and loved and tessellated into the mosaic of our being. To be an artist in the largest sense is to be fully awake to the totality of life as we encounter it, porous to it and absorbent of it, moved by it and moved to translate those inner quickenings into what we make.