1) to work at night;

2) that if you cannot gain what you want in one night to try again the next night;

3) to love your co-workers just as thieves love each other;

4) to be willing to risk your life even for a little thing;

5) not to attach too much value to things even though you have risked your life for them — just as a thief will resell a stolen article for a fraction of its real value;

6) to withstand all kinds of beatings and tortures but to remain what you are;

7) to believe that your work is worthwhile and not be willing to change it.

One particular fragment of it has stayed with me over the years — the kind of pure mountain spring on which the spirit is refreshed again and again with each visit.

When Cott asks what kind of life Dylan believes in, in the absence of such proof, he holds up “real life” — the reality of life he experiences “all the time,” but which lies “beyond this life.” (I am reminded here of Saul Bellow’s superb Nobel Prize acceptance speech from the same era: “Only art penetrates… the seeming realities of this world. There is another reality, the genuine one, which we lose sight of. This other reality is always sending us hints, which without art, we can’t receive.”)

From a thief you can learn

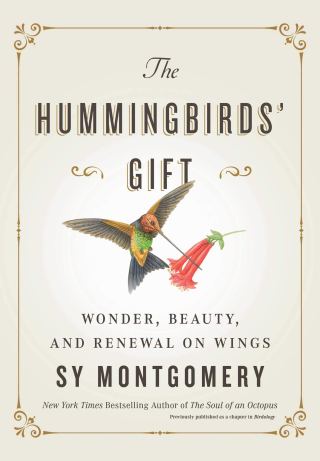

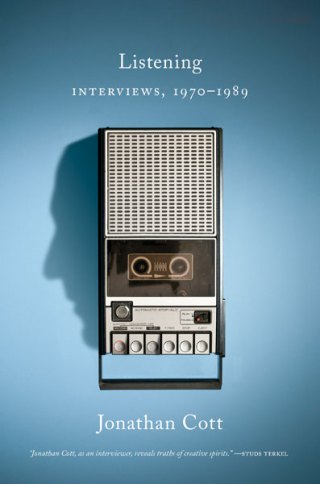

Just before Christmas in 1977, the thirty-six-year-old Bob Dylan sat down for a long conversation with Jonathan Cott. Included in Cott’s endlessly wonderful book Listening: Interviews, 1970–1989 (public library), it remains Dylan’s most soulful and deepest-fathoming interview, replete with his reflections on vulnerability, the meaning of integrity, and the power of music as an instrument of truth.

Complement with Dylan on the unconscious mind and Leonard Cohen’s lessons in the art of stillness, then revisit the four Buddhist mantras for turning fear into love.

1) to always to be happy;

2) never to sit idle;

3) to cry for everything you want.

This prompts the ever-erudite Cott to read for Dylan a teaching by the Hasidic rabbi Dov Baer, the Maggid of Mezeritch, in which he sees a mirroring of Dylan’s creative ethos and way of being in the world. It so captivates Dylan as “the most mind-blazing chronicle of human behavior,” exceeding in wisdom any of the “gurus and yogis and philosophers and politicians and doctors and lawyers,” that he asks for a copy to pin to his wall.

Two decades before string theorists formulated the holographic principle — a property of quantum gravity under which the three-dimensional universe we perceive might be a two-dimensional hologram — Dylan tells Cott:

We’re all wind and dust anyway… We don’t even have any proof that the universe exists. We don’t have any proof that we are even sitting here. We can’t prove that we’re alive.

From a child you can learn