His timeleess Meditations (public library), newly translated and annotated by the British classics scholar Robin Waterfield, were the original self-help — Marcus wrote these notebooks primarily as notes to himself while learning how to live: how to live with more agency, equanimity, and even joy in a world violently unpredictable at all times and especially so in his time.

There is, however, a peculiar modern phenomenon that might best be described as a culture of competitive trauma. In recent times, the touching human longing for sympathy, that impulse to have our suffering recognized and validated, has grown distorted by a troubling compulsion for broadcast-suffering and comparative validity. Personhoods are staked on the cards dealt and not the hands played, as if we evolved the opposable thumbs of our agency for nothing. In memoirs and reality shows, across infinite Alexandrian scrolls of social media feeds, the unlucky events of life have become the currency of attention and identification.

Because the modern mind calculates validity of vantage point by estimating the comparative value of suffering, it must be observed that, later in life, Marcus Aurelius had it easier than most of his contemporaries, being Emperor; it must also be observed that, earlier in life, he had it harder than most, being a fatherless child and a queer teenager in Roman antiquity, epochs before the notion of LGBTQ rights, or for that matter most human rights. It is hardly surprising that he turned to Stoicism for succor and training in living with the uncertainty of events and the certainty of loss.

It is not a new way of reframing personal narrative (which, after all, is the neuropsychological pillar of identity). It is a very old way, common to many of the world’s ancient traditions but most clearly and creatively articulated by the Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius (April 26, 121–March 17, 180).

Most people live with a great deal more suffering than is visible to even the most proximate and sensitive onlooker. Many have survived things both unimaginable and invisible to the outside world. This has been the case since the dawn of our species, for human nature has hardly changed beneath the continually repainted façade of our social sanctions — human beings have always been capable of inflicting tremendous pain on each other and capable of triumphal healing.

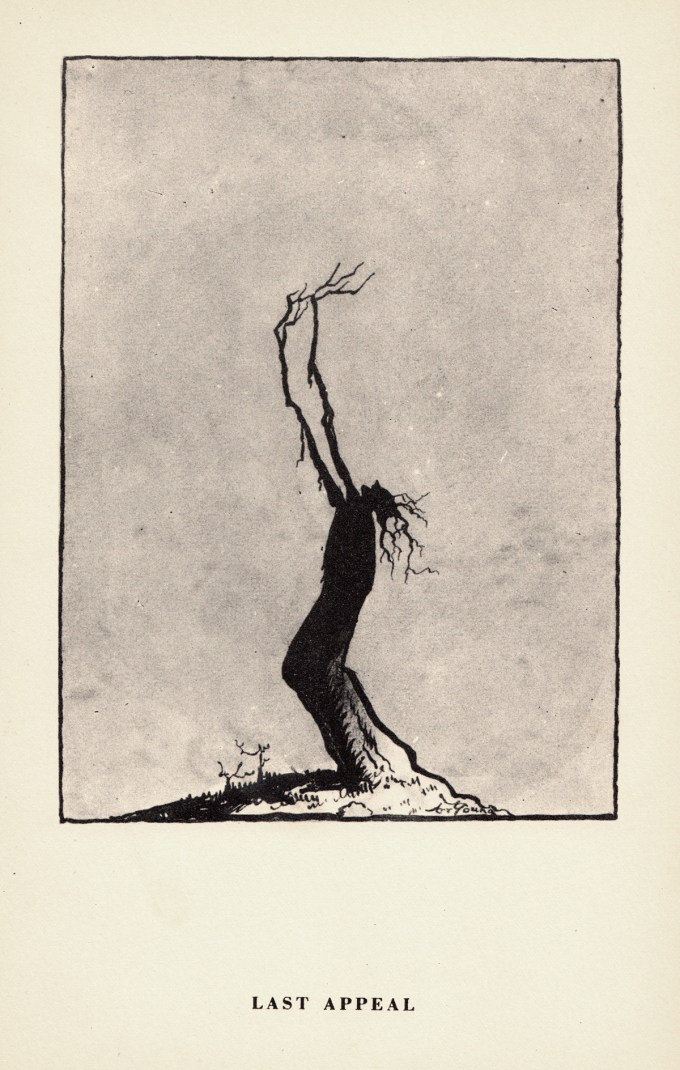

There is a way, with moderate moral imagination and considerable countercultural courage, to subvert this tendency without turning away from the reality and magnitude of suffering that we do live with — a way to esteem in attention and admiration not the unluckiness of what has happened to us but the luckiness that, despite it, we have become the people we are and have the lives we have by the sheer unwillingness to stay in that small dark place, which is at heart a willingness to be larger than our hurt selves.

Can what happened to you stop you from being fair, high-minded, moderate, conscientious, unhasty, honest, moral, self-reliant, and so on — from possessing all the qualities that, when present, enable a man’s nature to be fulfilled? So then, whenever something happens that might cause you distress, remember to rely on this principle: this is not bad luck, but bearing it valiantly is good luck.

With an eye to “what human nature wants” — what life ultimately demands as it lives itself through us, and what our highest answer is — he concludes:

In one of those self-counsels, Marcus Aurelius considers the key to regarding one’s own life, and living it, with positive realism:

Complement with an equally counterintuitive and perspective-broadening modern case for the luckiness of death and Alan Watts on the ambiguity of good and bad luck, then revisit other highlights from the indispensable Meditations: Marcus Aurelius on how to handle disappointing people, the key to living with presence, the most potent motivation for work, and how to begin each day for maximum serenity of mind.

Be like a headland: the waves beat against it continuously, but it stands fast and around it the boiling water dies down. “It’s my rotten luck that this has happened to me.” On the contrary, “It’s my good luck that, although this has happened to me, I still feel no distress, since I’m unbruised by the present and unconcerned about the future.” What happened could have happened to anyone, but not everyone could have carried on without letting it distress him. So why regard the incident as a piece of bad luck rather than seeing your avoidance of distress as a piece of good luck? Do you generally describe a person as unlucky when his nature worked well? Or do you count it as a malfunction of a person’s nature when it succeeds in securing the outcome it wanted?