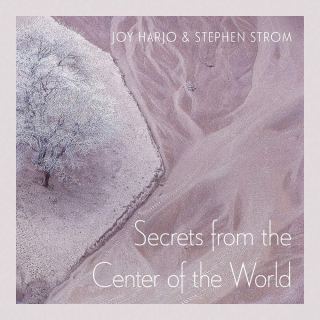

In 1989, long before she became Poet Laureate of the United States, Joy Harjo entwined visions with the astronomer and photographer Stephen Strom in Secrets from the Center of the World (public library) — a slender, splendid installment in the University of Arizona’s wonderful Sun Tracks series, celebrating Native American literary art long before Native representation rose to the fore of the American mainstream, long before the English language awakened to how deeply its etymological reliance on the Earth permeates words as mundane as mainstream.

Strom — who received his doctoral degree from Harvard, studied the formation of star and planetary systems at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, taught astronomy in Emily Dickinson’s hometown for a decade and a half, and spent three decades photographing the Southwest — renders Earth otherworldly in his photographs, spare and solitary, edged in by invisible implied horizons, the way the desert implies life, the way poetry makes life visible. Revealing the fractal patterning of nature, his subtle geometries of shape and color reach beyond the three spatial dimensions to intimate the dimension of time.

I can hear the sizzle of newborn stars, and know anything of meaning, of the fierce magic emerging here. I am witness to flexible eternity, the evolving past, and I know we will live forever, as dust or breath in the face of stars, in the shifting pattern of winds.

This earth has dreamed me to stand on the rise of this highway, to admire who she has become.

This land is a poem of ochre and burnt sand I could never write, unless paper were the sacrament of sky, and ink the broken line of wild horses staggering the horizon several miles away. Even then, does anything written ever matter to the earth, wind, and sky?

My cheek is flat against memory described by stone and lichen. The center of the world is within reach. It is as familiar as your name, as strange as monsters in your sleep.

“Place and a mind may interpenetrate till the nature of both is altered,” the trailblazing Scottish mountaineer and poet Nan Shepherd wrote into the void of self-elected obscurity decades before her work was posthumously rediscovered as a rare masterpiece of landscape poetics irradiated by the human search for meaning. A generation later, another trailblazing woman of uncommon poetic sensibility and intimate relationship to the land echoed the sentiment in her own art, into her native canyons of the American Southwest: “It’s true that landscape forms the mind. If I stand here long enough I’ll learn how to sing.”

Complement Secrets from the Center of the World with poet Mark Strand’s kindred collaboration with painter Wendy Mark around the landscape of the sky, 89 Clouds, then revisit painter, poet, and philosopher Etel Adnan’s Journey to Mount Tamalpais — her stunning landscape-lensed meditation on time, self, impermanence, and transcendence.

These smoky bluffs are old traveling companions, making their way through millennia. Ask them if you want to know about the true meaning of history. You’ll have to offer them something more than one good story, and need to understand the patience of stones.

If all events are related, then what story does a volcano erupting in Hawaii, the birth of a woman’s second son near Gallup, and this shoulderbone of earth made of a mythic monster’s anger construct? Nearby a meteor crashes. Someone invents aerodynamics, makes wings. The answer is like rushing wind: simple faith.

Emerging from the lovely call-and-response between Strom’s photographs and Harjo’s short lyrical reflection is a subtle meditation on the interpenetration of place and mind, of landscape and the human spirit. Contemplating the ochre canyons and the golden valleys, the pleated sierras and the billowing mudhills, the frosty branches of the winter trees and the summer-blazed strata of sandstone, she unfolds the origami of deep time into a note some ghost-mother left for her ghost-child long ago on the edge of the kitchen table, on the edge of the world, inscribed with the meaning of being human.

Near Round Rock is a point of balance between two red stars. Here you may enter galactic memory, disguised as a whirlpool of sand, and discover you are pure event mixed with water, occurring in time and space, as sheep, a few goats, graze, keep watch nearby.

Harjo — a member of the Creek Nation — meets the cosmological sensibility of the photographs with a private cosmogony drawn from that ancient human impulse to locate ourselves in relation to the universe, to make meaning in the sliver of spacetime on which chance has perched us to live out our lives between the scale of protozoa and the scale of galaxies. She envelops each photograph in a short prose-poem that takes the image as its origin point of contemplation, then radiates centrifugally into a miniature universe of metaphor and meaning-making — the mark of all great poetry.

My house is the red earth; it could be the center of the world. I’ve heard New York, Paris, or Tokyo called the center of the world, but I say it is magnificently humble. You could drive by and miss it. Radio waves can obscure it. Words cannot construct it, for there are some sounds left to sacred wordless form. For instance, that fool crow, picking through trash near the corral, understands the center of the world as greasy strips of fat. Just ask him. He doesn’t have to say that the earth has turned scarlet through fierce belief, after centuries of heartbreak and laughter — he perches on the blue bowl of the sky, and laughs.

In winter it is easier to see what my death might look like, over there, disappearing into the misty, spotted rocks.

Harjo looks at the Moon and sees “an ancient mountain lion who shifts his bones on a starry branch,” looks at the branches of the tamaracks and sees crows “leaning over the edge of the world, tasting the wind blown up from a pool of newly born planets,” looks at the land and sees its elemental poetry, sees how it humbles her own art, her own existence, every human existence and all of our art.