As he began his next series, nature and night beckoned to him more and more .

The master accepted him, conferring upon him the lyrical name Hasui — an ideogram of his family name fused with the name of his boyhood school, most closely translated translated as “water springing from the source.”

“After you have exhausted what there is in business, politics, conviviality, love, and so on — have found that none of these finally satisfy, or permanently wear — what remains?” the aging Walt Whitman asked in his diary as he contemplated what makes life worth living while recovering from a paralytic stroke, then answered: “Nature remains… the trees, fields, the changes of seasons — the sun by day and the stars of heaven by night.”

And then, on an otherwise ordinary Saturday the autumn after his fortieth birthday, the convergence boundary between two tectonic plates deep in the body of the Earth ruptured, unleashing the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923. It leveled his workshop, destroying the finished woodblocks and fomenting in him an even more intimate sense of the sublimity of nature.

When the business went bankrupt in the early twentieth century, the twenty-six-year-old Kawase devoted himself wholly to art, applying to apprentice with one of the great masters of transitional Japanese woodblock printing. The master rejected him, encouraging him to broaden his sensibility and to develop his style by studying Western painting first. The young man obliged.

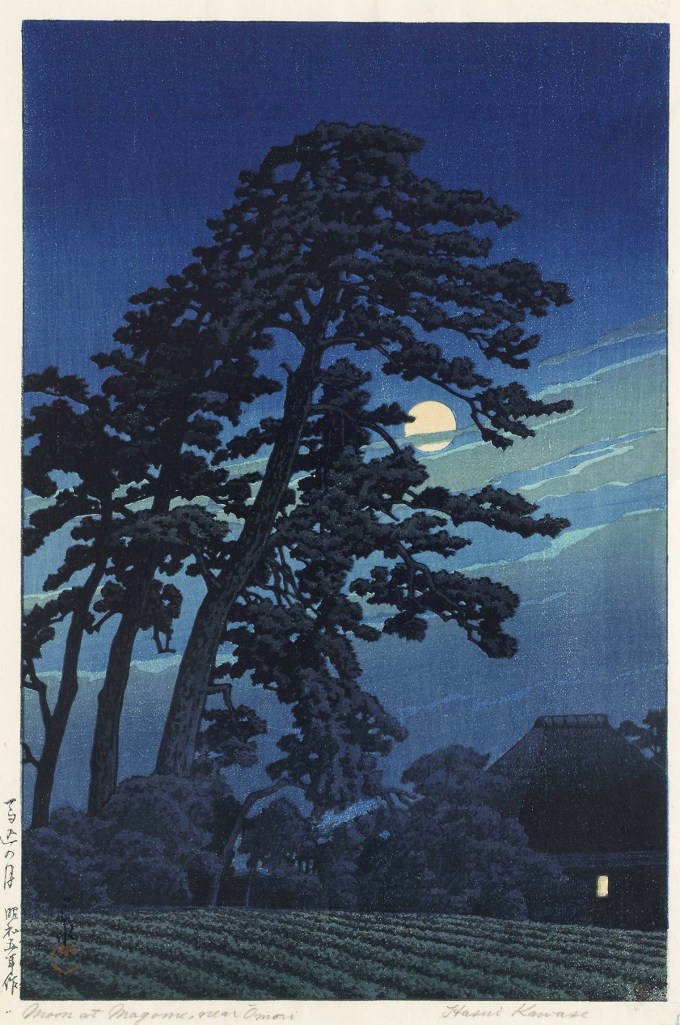

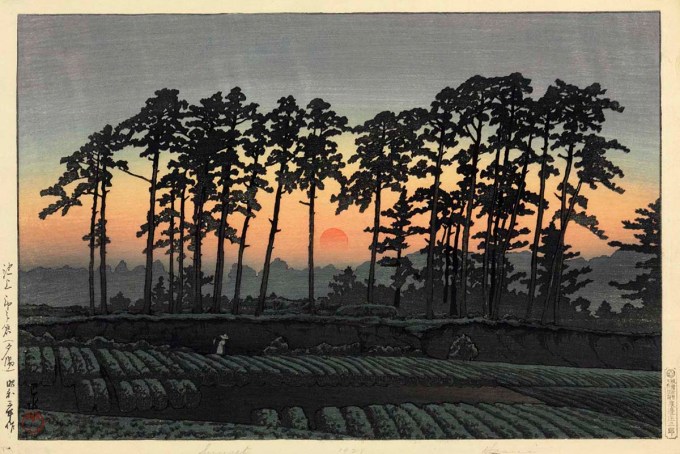

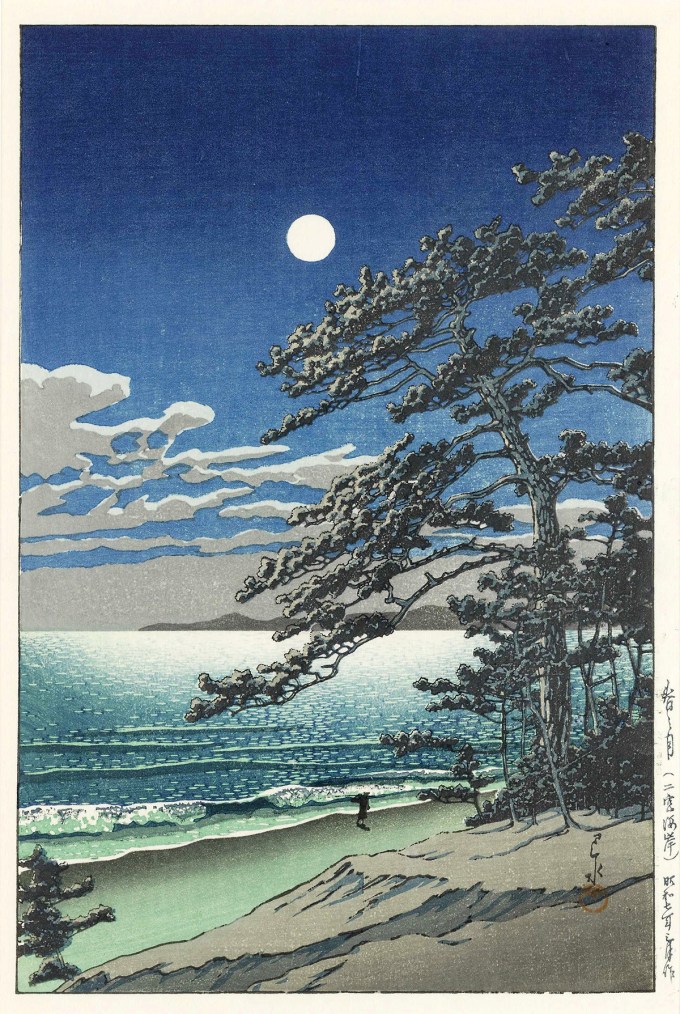

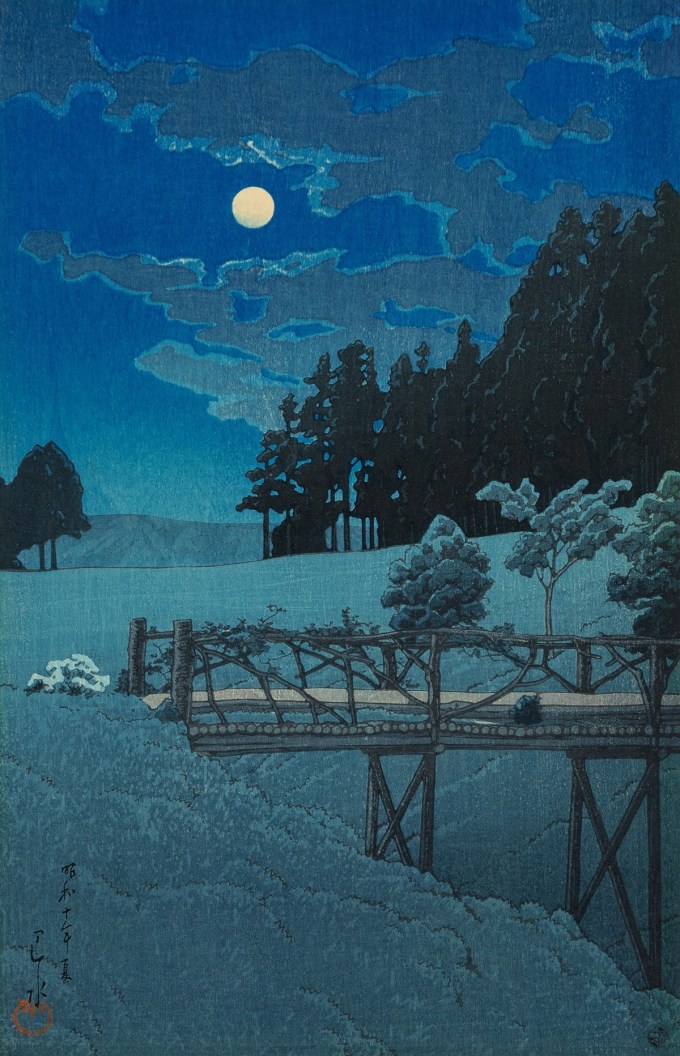

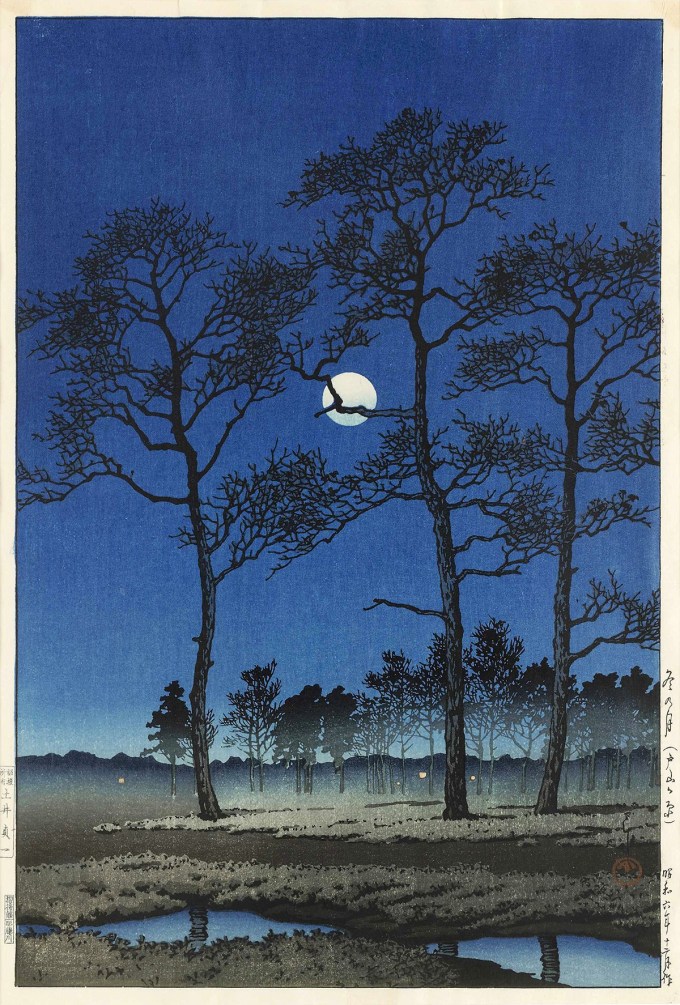

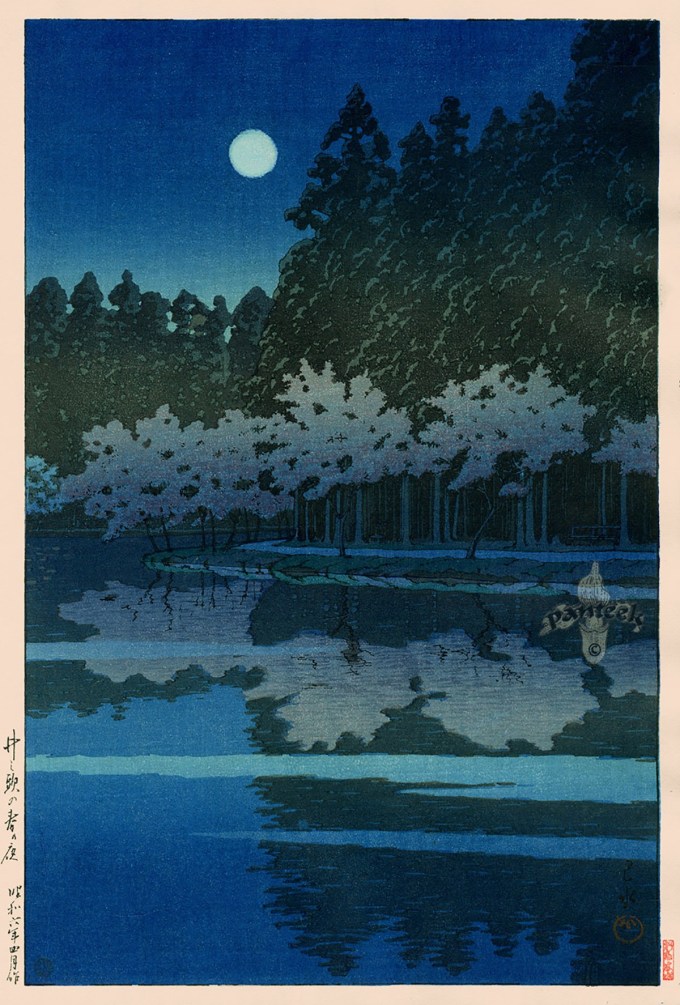

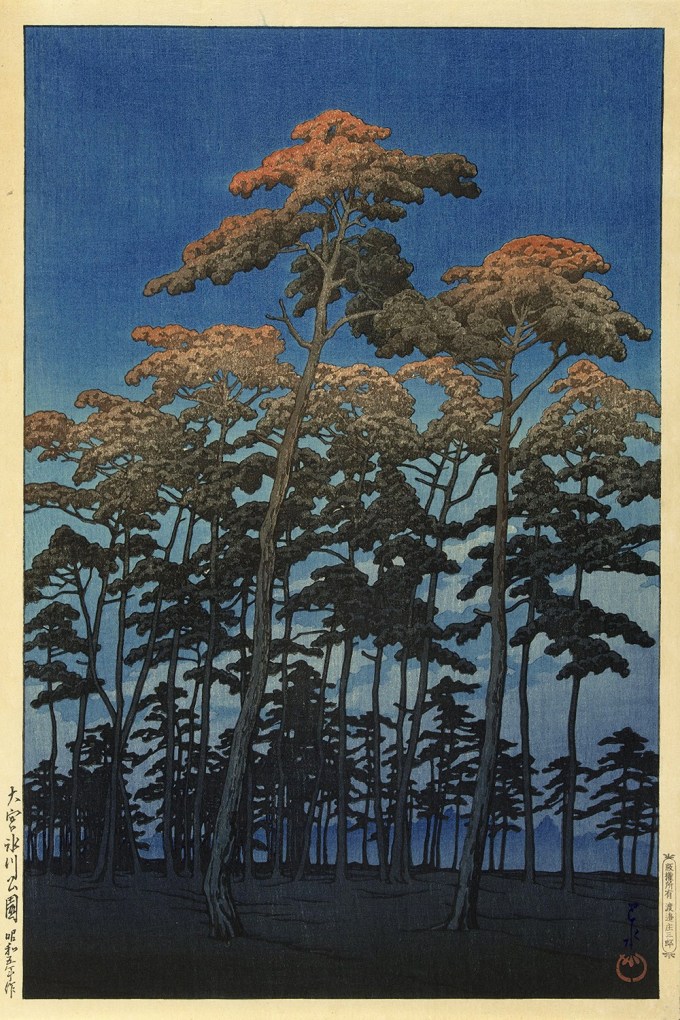

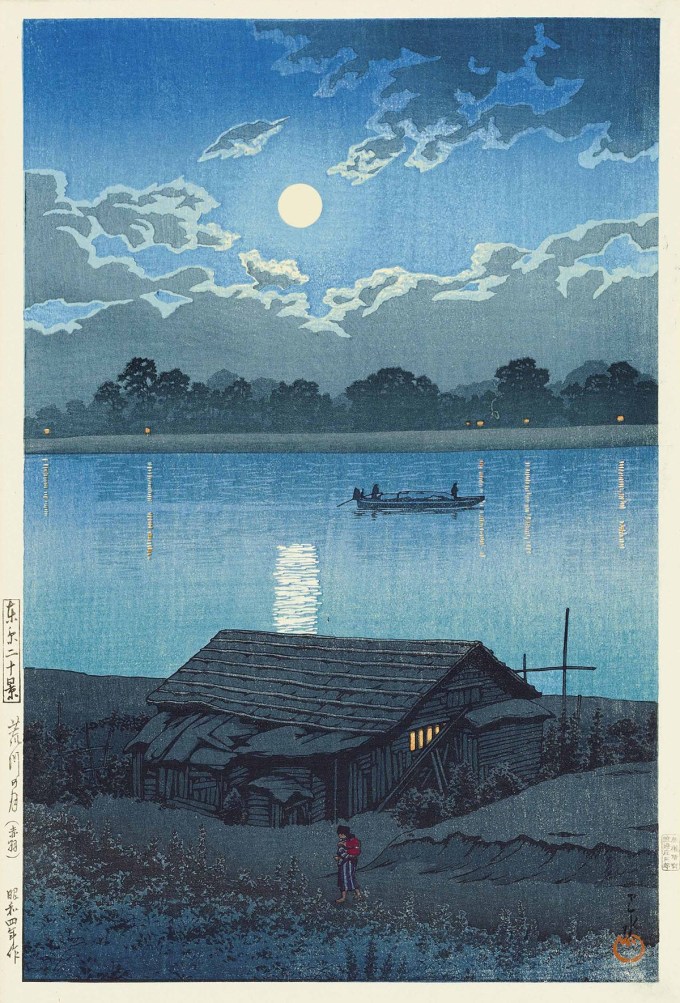

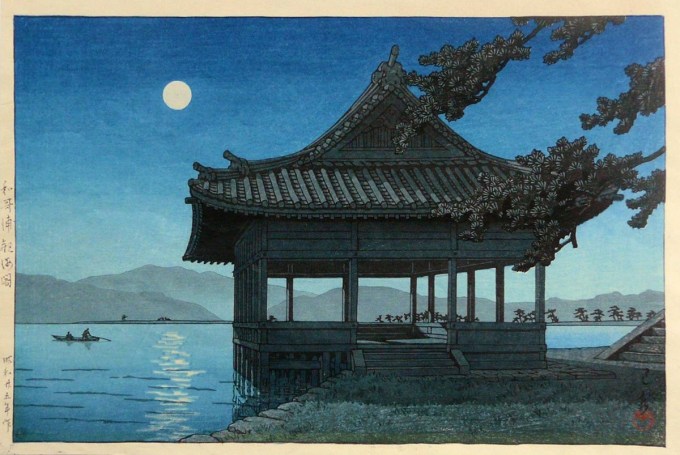

But among all of nature’s beauties, nothing inspired him more than trees — those eternal muses of scientists, artists, philosophers, and poets alike — and what Margaret Fuller so unforgettably called “that best fact, the Moon.”

In the final year of his life, the Japanese government classified Hasui as a Living National Treasure. Comparable to the American National Medal of Arts and Humanities, Japan’s highest civilian honor is bestowed upon those whose life’s work renders them, in what may be the most poetic government certification in any language, “Preservers of Important Intangible Cultural Properties.”

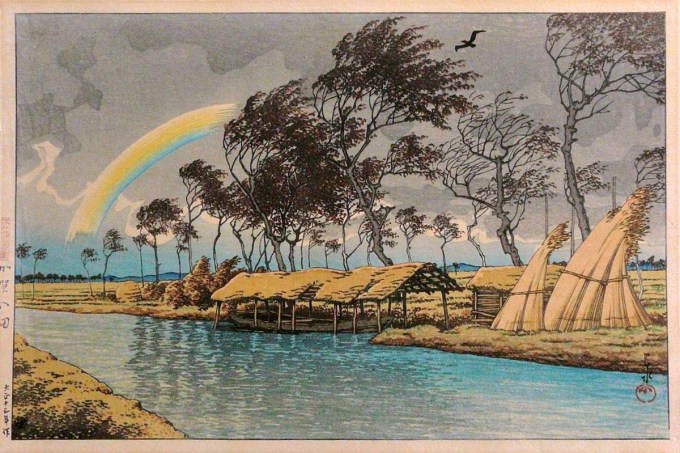

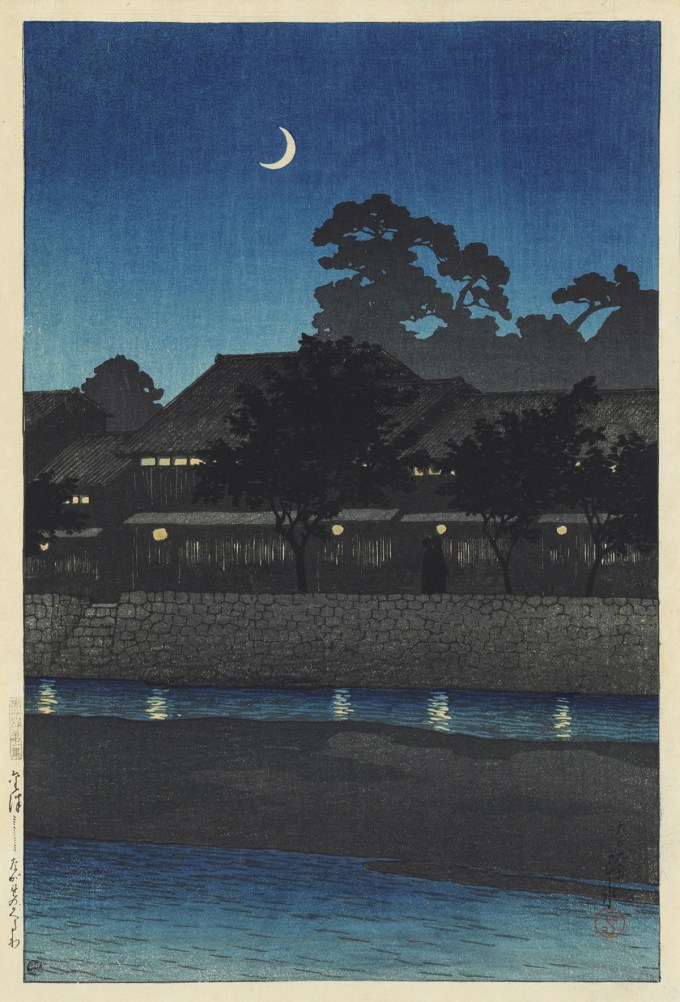

Over the next thirty-five years, Hasui became a master of shin hanga — the “new prints” movement fusing traditional Japanese art, the art of shadows, with the Western aesthetics of light and the European novelty of perspective. He went on to create several hundred consummate woodblock prints, watercolors, oil paintings, and hanging scrolls, animated by a tender reverence for the beauty and majesty of nature. One hundred of them are collected in the lavish annotated volume Visions of Japan: Kawase Hasui’s Masterpieces (public library).

Hasui was thirty-five — the age Whitman was when he staggered the world with his Leaves of Grass — when he made his artistic debut with a series of experimental woodblock prints, depicting the mostly empty streets of Tokyo and the unpeopled landscapes of the countryside.

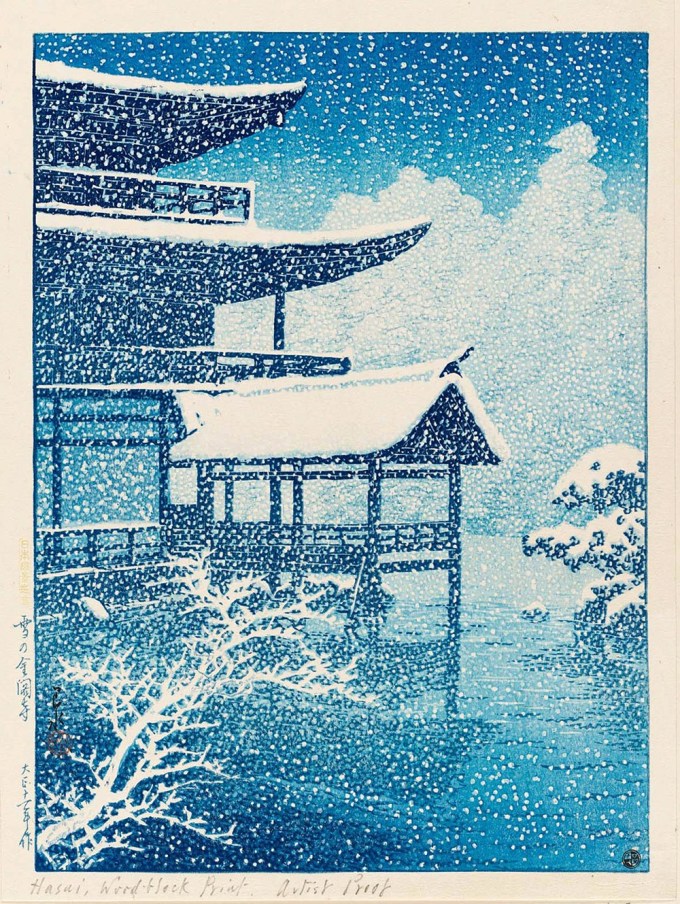

Hasui captured the enchantment of snowfall with especial loveliness, his intricate lines challenging the artisans he employed in carving his woodblock designs to rise to new levels of craftsmanship.

Born into a Tokyo family of rope and thread merchants, Hasui Kawase (May 18, 1883–November 7, 1957) grew up dreaming of becoming an artist. His parents pressed him to continue in their path, but he persisted in following his own, drawing quiet inspiration from the example of his maternal uncle — the creator of the first manga magazine.

In landscape after landscape, the majestic silhouettes of the matsu (Japan’s iconic pine trees, symbols of fortitude and courage) and the sugi (the enormous old-growth cedars, symbols of power and longevity) reach into the noctrune toward the crescent and lean into the gloaming hour, backlit by the full Moon.

Two years later, he applied again.

He did take over the family business, but he was moonlighting in art while running it — sketching from nature, copying one master’s woodblock prints, learning brush painting from another.

Complement with Japanese-American artist Chiura Obata’s stunning paintings of Yosemite from the same era, then revisit a very different take on tree silhouettes from Hasui’s American contemporary Art Young.

A century after Whitman’s birth, on the other side of a globe newly disillusioned with its own humanity after the First World War, a young Japanese man was embarking on a life of celebrating the inexhaustible consolations of nature in uncommonly poetic visual art.