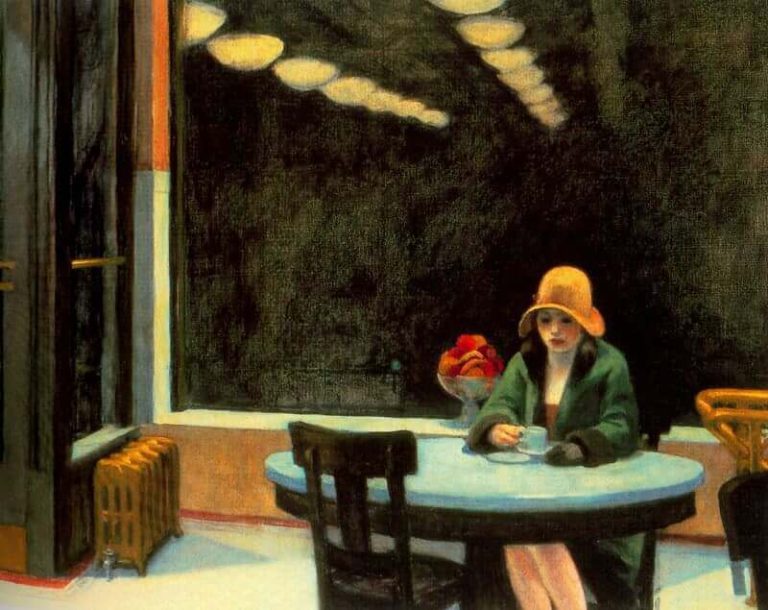

Consciousness… is a particular state of mind resulting from a biological process toward which multiple mental events make a contribution… These contributions converge, in a regimented way, to produce something quite complex and yet perfectly natural: the encompassing mental experience of a living organism caught, moment after moment, in the act of apprehending the world within itself and, wonder of wonders, the world around itself.

The Brain — is wider than the Sky —

For — put them side by side —

The one the other will contain

With ease — and you — beside —

This view defies both extremes that dominate our present models of consciousness, each unimaginative and intellectually unambitious in its own way, as all extremes invariably are: materialism, which confines it to the neural activity of the brain, and mysticism, which places it entirely outside the contours of the body and beyond the reach of scientific investigation. Damasio writes:

The Brain is deeper than the sea —

For — hold them — Blue to Blue —

The one the other will absorb —

As sponges — Buckets — do —

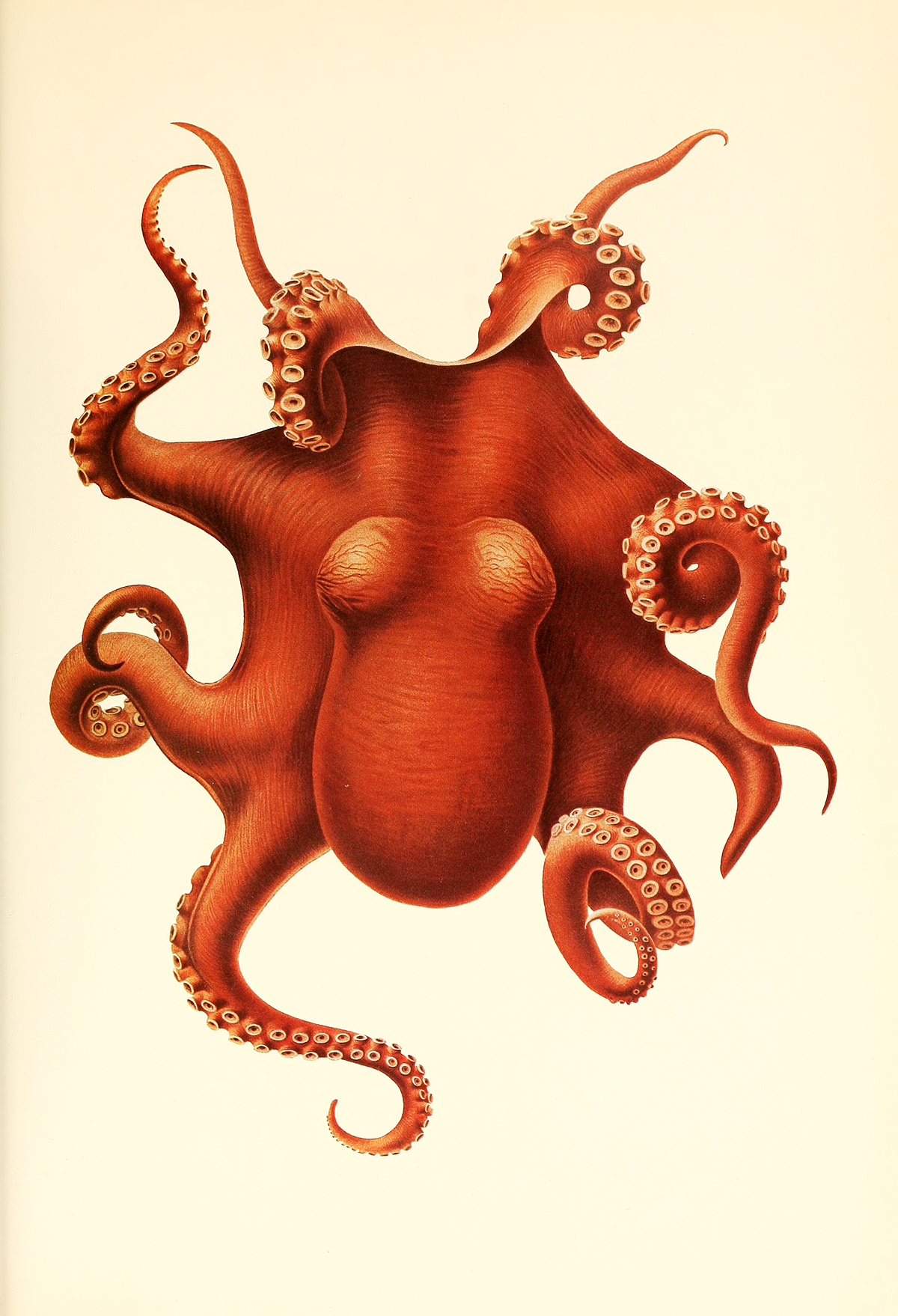

Feeling probably began its evolutionary history as a timid conversation between the chemistry of life and the early version of a nervous system within one particular organism… Those timid beginnings provided each creature with an orientation, a subtle adviser as to what to do next or not to do or where to go. Something novel and extremely valuable had emerged in the history of life: a mental counterpart to a physical organism.

And this is the optimistic underdone I hear in Damasio’s model: By understanding as a full-body phenomenon the consciousness that lenses our view of reality and shapes our life-experience, we can not only become better stewards of our own bodies and of the planet we share with other bodies, human and nonhuman, but we can begin to dismantle the artificial hierarchies and categories by which we have long bolstered our creaturely centrality across the various scales and spectra of existence, from Ptolemism to anthropocentrism to racism, choosing instead to be both humbled and hallowed by the evolutionary wonder of consciousness.

This is so because feelings are not purely mental phenomena but delicate interleavings of body and mind — the serpent of consciousness biting its own tail:

Consciousness gathers together the bits of sapience that reveal, by dint of their coincident presence, the mystery of belonging. They tell me — or you — sometimes in the subtle language of feeling, sometimes in ordinary images or even in words translated for the occasion, that yes, lo and behold, it is me — or you — thinking these things, seeing these sights, hearing these sounds, and feeling these feelings. The “me” and “you” are identified by mental components and body components.

The power of feelings comes from the fact that they are present in the conscious mind: technically speaking, we feel because the mind is conscious, and we are conscious because there are feelings… Feelings were and are the beginning of an adventure called consciousness.

We are quite familiar with the direct way in which illness gives way to discomfort and pain or exuberant health produces pleasure. But we often overlook the fact that psychological and sociocultural situations also gain access to the machinery of homeostasis in such a way that they too result in pain or pleasure, malaise or well-being. In its unerring push for economy, nature did not bother to create new devices to handle the goodness or badness of our personal psychology or social condition. It makes do with the same mechanisms.

One, which Damasio does not address directly — perhaps because it is self-evident, or perhaps because he prefers not to ruffle the feelings (that is, the consciousnesses) of those who take flight from evidence in such beliefs — is a bold debunking of certain escapist fantasies from our creaturely reality: both the fantasies haunted by our parochial past and its various religious mythologies of an immortal soul that survives the death of the body (“soul” being the conceptual placeholder for consciousness before the word was coined), and the fantasies haunting the techno-utopian future with Silicon dreams of machine consciousness and technology-assisted ways of preserving human consciousness beyond the lifespan of the body by digitizing and migrating the contents of the brain alone.

This understanding defeats a popular dictum of the self-help world — the comfort-blanket belief that one cannot cause another person’s feelings or be caused to feel a certain way by another person’s actions. No: One person can very much make choices and take actions toward another that impact and impair the other person’s homeostasis — that is, the organism’s sense of stability and safety — thus producing in that other person the negative feelings that are the organism’s feedback loop to protect homeostasis: pain, our primary signal for course-correction.

Ultimately, we are puppets of both pain and pleasure, occasionally made free by our creativity.

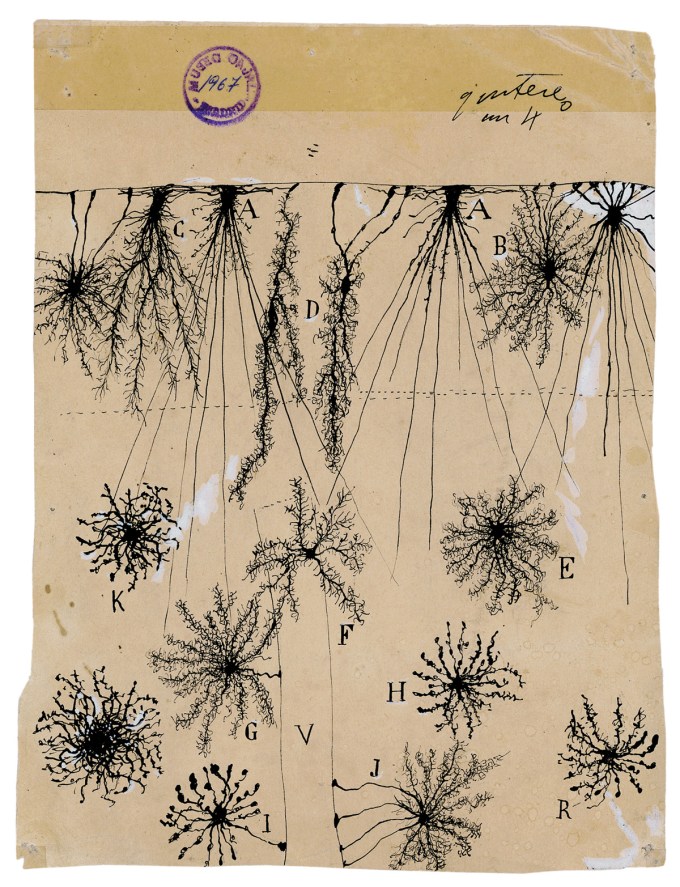

These astonishing afterthoughts of evolution became the stage on which the theater of consciousness plays out. Damasio explains:

With an eye to this essential parameter of ownership — the great revelation made possible by feeling — Damasio writes:

What does it mean to say “I am conscious”? At the simplest level imaginable, it means to say that my mind, at the particular moment in which I describe myself as conscious, is in possession of knowledge that spontaneously identifies me as its proprietor… Some knowledge about the current operations of my body [and] some knowledge as retrieved from memory, about who I am at the moment and about who I have been, recently and in the long ago past… [produce] mental states imbued with feeling and a sense of personal reference.

Mapping the four-billion-year history of living organisms along its branching streams, Damasio envisions the distributary that led to us as a cascade of three evolutionary stages: being, feeling, and knowing, which continue to coexist in each of us modern sapiens, coursing through the various anatomical and functional systems that give us life. No invention of nature, Damasio argues, powered a greater leap than the emergence of nervous systems, which made minds possible — but their inception, like so many great inventions, was an unbidden byproduct of solving pressing necessities:

These images furnish representations of the world, making it comprehensible and therefore survivable as the organism navigates that world by a sort of native biological intelligence that powers the basic self-care necessary for maintaining homeostasis — maintenance that eventually comes aglow with feeling. More complex organisms can manipulate those images, integrating them into a system of reference we call knowledge, which the nervous system makes explicit by creating patterns and committing them to memory, so that the organism can plan, reason, and reflect.

Not surprisingly, feelings are important contributors to the creation of a “self,” a mental process animated by the state of the organism, and are anchored in its body frame (the frame constituted by muscular and skeletal structures), and oriented by the perspective provided by sensory channels such as vision and hearing.

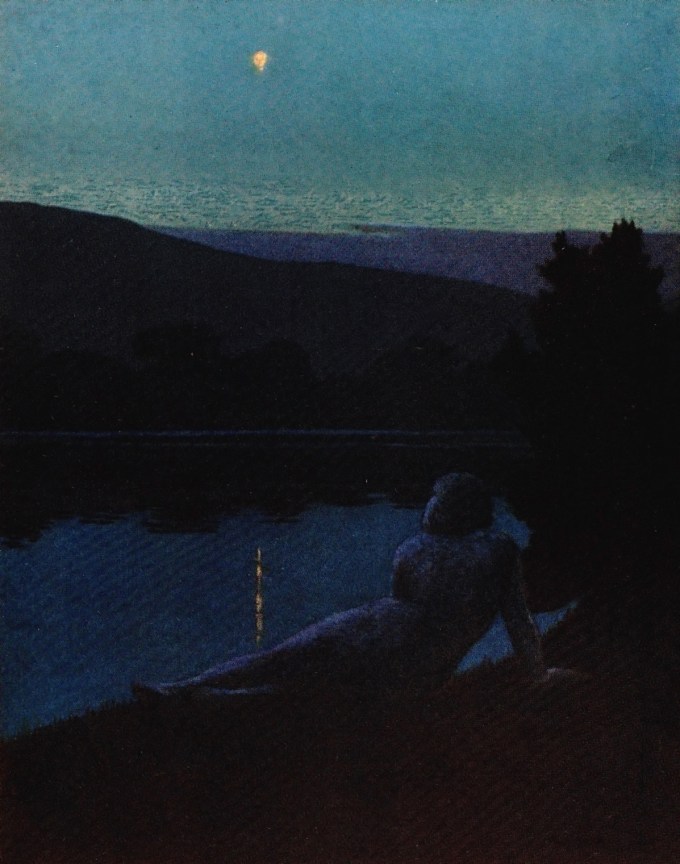

Ultimately, feeling conspires with minding and knowing to give rise to the system-level phenomenon of consciousness from the infrastructure of the nervous system and the body: Our perceptual senses — sight, touch, hearing, smell, taste — render the external world in mental images; our feelings render the internal world, representing in our own minds the state of our bodies — those roiling inner worlds in which all sense of wellbeing is won or lost. From this sense of ownership of ourselves arises the phenomenon of consciousness — the functions that makes possible the novel responses we call adaptation, or art.

Through this essential feedback loop of feeling, we are able to assess how we are doing at the basic task of living — not only at the binary state of whether or not we are staying alive, but on the qualitative scale of how well our actual experience maps onto our optimal experience. Pleasure and pain, love and longing — these are all varieties of conscious experience that allow us to fine-tune our flourishing. They all arise when stimuli trigger molecular messages that travel from body tissues and organs, through nerve terminals, into the central nervous system and the brain, producing mental images that give us valuable information we experience as emotional states, which serve to steer us toward corrective action.

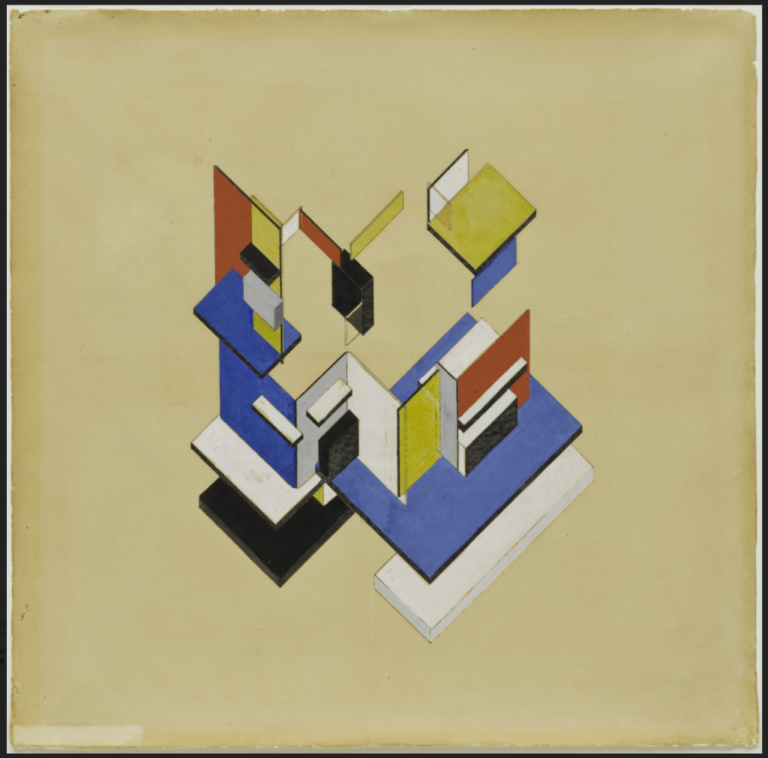

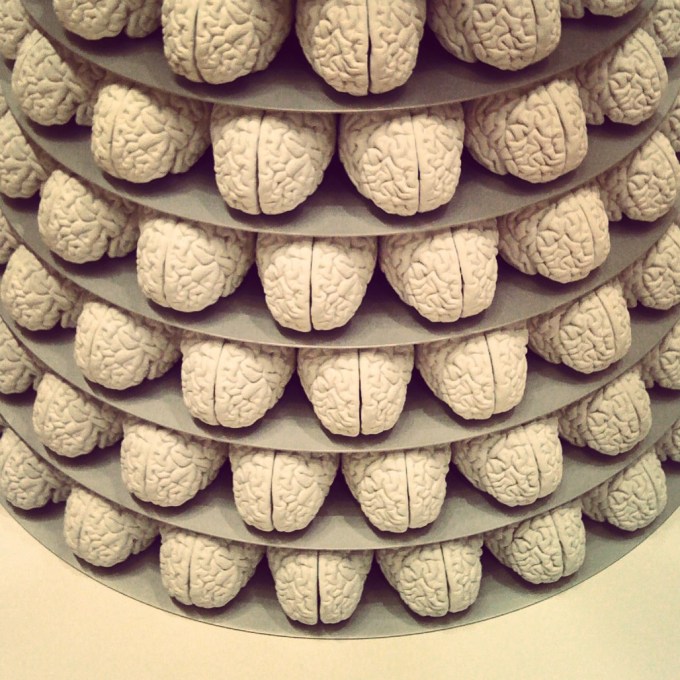

Turn a mind inside out and spill its contents. What do you find? Images and more images, the sorts of images that complicated creatures, such as we are, manage to generate and combine in a forward-flowing stream. This is the very “stream” that immortalized William James and gave fame to the word “consciousness” because the two words were so often paired in the phrase “stream of consciousness.” But… the stream… is simply made of images whose near-seamless flow constitutes a mind.

Turn a mind inside out and spill its contents. What do you find? Images and more images, the sorts of images that complicated creatures, such as we are, manage to generate and combine in a forward-flowing stream. This is the very “stream” that immortalized William James and gave fame to the word “consciousness” because the two words were so often paired in the phrase “stream of consciousness.” But… the stream… is simply made of images whose near-seamless flow constitutes a mind.

Turn a mind inside out and spill its contents. What do you find? Images and more images, the sorts of images that complicated creatures, such as we are, manage to generate and combine in a forward-flowing stream. This is the very “stream” that immortalized William James and gave fame to the word “consciousness” because the two words were so often paired in the phrase “stream of consciousness.” But… the stream… is simply made of images whose near-seamless flow constitutes a mind.

Turn a mind inside out and spill its contents. What do you find? Images and more images, the sorts of images that complicated creatures, such as we are, manage to generate and combine in a forward-flowing stream. This is the very “stream” that immortalized William James and gave fame to the word “consciousness” because the two words were so often paired in the phrase “stream of consciousness.” But… the stream… is simply made of images whose near-seamless flow constitutes a mind.

Turn a mind inside out and spill its contents. What do you find? Images and more images, the sorts of images that complicated creatures, such as we are, manage to generate and combine in a forward-flowing stream. This is the very “stream” that immortalized William James and gave fame to the word “consciousness” because the two words were so often paired in the phrase “stream of consciousness.” But… the stream… is simply made of images whose near-seamless flow constitutes a mind.

Turn a mind inside out and spill its contents. What do you find? Images and more images, the sorts of images that complicated creatures, such as we are, manage to generate and combine in a forward-flowing stream. This is the very “stream” that immortalized William James and gave fame to the word “consciousness” because the two words were so often paired in the phrase “stream of consciousness.” But… the stream… is simply made of images whose near-seamless flow constitutes a mind.

This is where our physiology and psychology converge. Offering neuoroscientific affirmation of Hannah Arendt’s searing philosophical-political indictment that “society has discovered discrimination as the great social weapon by which one may kill men without any bloodshed,” Damasio writes:

Any theory that bypasses the nervous system in order to account for the existence of minds and consciousness is destined to failure. The nervous system is the critical contributor to the realization of minds, consciousness, and the creative reasoning that they allow. But any theory that relies exclusively on the nervous system to account for minds and consciousness is also bound to fail. Unfortunately, that is the case with most theories today. The hopeless attempts to explain consciousness exclusively in terms of nervous activity are partly responsible for the idea that consciousness is an inexplicable mystery. While it is true that consciousness, as we know it, only fully emerges in organisms endowed with nervous systems, it is also true that consciousness requires abundant interactions between the central part of those systems — the brain proper — and varied non-nervous parts of the body.

Feelings… provide the urge and the incentive to behave according to the information they carry and do what is most appropriate for the current situation, be it running for cover or hugging the person you have missed.

In the remainder of Feeling & Knowing, Damasio goes on to detail the three universes of experience from which our mental images spring, how our chemistry and our skeletal frame converge to produce our sense of belonging to ourselves, the role of affect in how we allocate attention, and much more, including how the discoveries of science in the epochs since Emily Dickinson penciled her far-seeing verse have clarified her core insight:

Once being and feeling are structured and operational, they are ready to support and extend the sapience that constitutes the third member of the trio: knowing.

Dickinson was candidly committed to an organic view of mind and to a modern conception of the human spirit. And yet, in the end, what turned out to be wider than the sky was not the brain but life itself, the begetter of bodies, brains, minds, feelings, and consciousness. What is more impressive than the entire universe is life, as matter and process, life as inspirer of thinking and creation.

Once experiences begin to be committed to memory, feeling and conscious organisms are capable of maintaining a more or less exhaustive history of their lives, a history of their interactions with others and of their interaction with the environment, in brief, a history of each individual life as lived inside each individual organism, nothing less than the armature of personhood.

Complex, multicellular organisms with differentiated systems — endocrine, respiratory, digestive, immune, reproductive — were saved by nervous systems, and organisms with nervous systems came to be saved by the things nervous systems invented — mental images, feelings, consciousness, creativity, cultures.