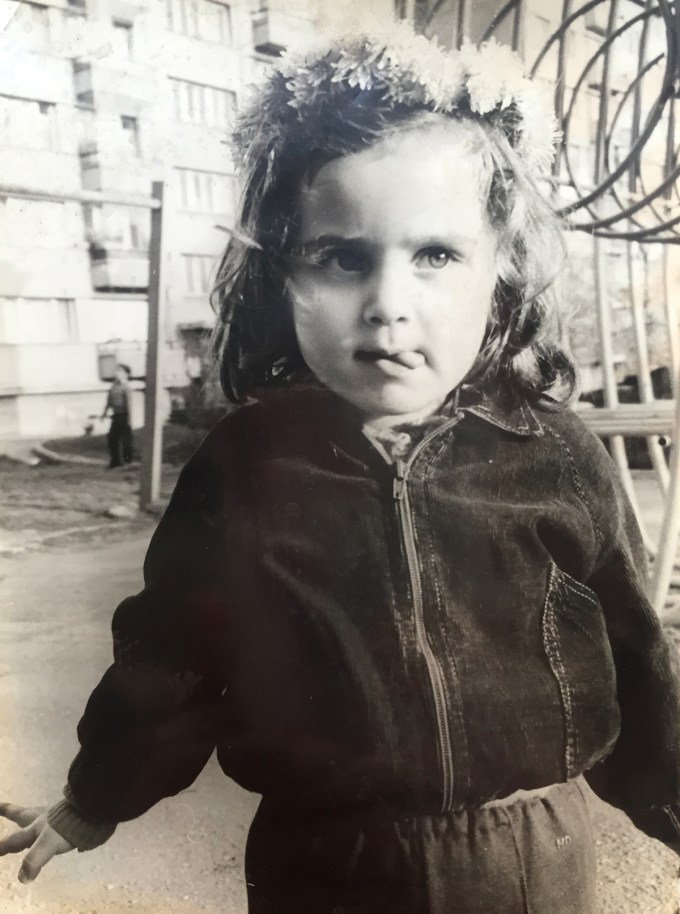

We are born without choosing to, to parents we haven’t chosen, into bodies and borders we haven’t chosen, to exist in a region of spacetime we haven’t chosen for a duration we don’t choose. As physicists know, we don’t choose the particular atoms that constellate our particular selves or the neural configurations that fire our consciousness. In consequence, as James Baldwin knew, we don’t even choose whom we love.

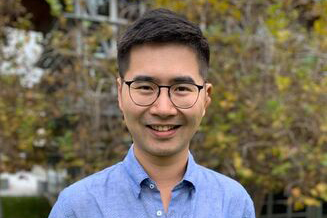

Brain Pickings was born on October 23, 2006 as an improbable idea in a young mind only just becoming literate in the language of life. Fifteen years hence, it is reborn as The Marginalian — reborn as what it has always been beneath the ill-fitting name chosen by a twenty-two-year-old immigrant in whose ear the tired puns and idioms of a non-native language rang fresh and full of wonder: an evolving record and ongoing celebration of my readings and my loves, of all that makes me feel most alive.

This is always, at bottom, a discourse with oneself: me with myself, in writing it; you with yourself, in reading it. We bring to anything — a book, a love — the whole of what we are, projecting onto it every experience we have ever had and every unanswered question reverberating through the deepest chambers of our being. If it is worthy — the book, as the love — and if we are lucky, it reflects us back to ourselves magnified yet transformed, luminous with a larger self-image of possibility, more alive, more awake. Better able to see how our temporal, marginal lives shimmer with meaning. Better able to see ourselves as the makers of it, whether we call it love or art.

A challenge arises when we make something over a long period of time. As we evolve — as we add experiences, impressions, memories, deepening knowledge and self-knowledge to the combinatorial pool from which all creative work springs — what we make evolves accordingly; it must, if we are living widely and wisely enough. Eventually, the name we once chose for it begins to feel not like a choice but like a constraint, an ill-fitting corset ribbed with the ossified sensibility of a former self. Joan Didion may be right that “we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not,” but we are also well advised to welcome with a largehearted embrace the blooming possibilities within us — the people we are in the ongoing course of becoming, the people we will have been when our atoms give way to our afterglow.

In the margins of books, in the margins of life as commonly conceived by our culture’s inherited parameters of permission and possibility, I have worked out and continue working out who I am and who I wish to be — a private inquiry irradiated by the ultimate question, the great quickening of thought, feeling, and wonder that binds us all: What is all this?

More and more, the curatorial aspect — the “picking” part of Brain Pickings — subsided, as did the purely cerebral aspect — the “brain” part — giving way to the editorial, the contemplative, the full integration of thought and feeling that pulsates beneath all things creative and alive. And so there is no change in course beneath the change in name — nothing about the site or its weekly email summary will alter, other than my daily despair at living with a name that neither fits nor foments the private well of wonder from which it all springs. It remains freely offered and supported by donations, as it always has been. (It is not always easy to make a life and a labor of love in the margins of possibility — if you have lent a helping hand over the years, I appreciate you.) It remains an exercise in marginalia on readings and reckonings, a discourse with these works of wonderment.

Over the years, I grew up and grew on these pages — more than six million of them, if one were to paginate and print everything I have published on the site over the years, dwarfing the 600 pages of Figuring and microscopizing the The Snail with the Right Heart. I filled this infinite scroll with my reflections on what I was reckoning with — my marginalia on life and the most important things I was learning about it along the way, often through reading, often from people and ideas marginalized by culture, erased by the collective selective memory we call history, because they were in some way too other, too ahead of their time or apart from its mores, saw too clearly through the willful blindnesses of their era or bent their vision too far past its horizons of possibility.

But amid our slender repertoire of agency are the labels we choose for our labors of love — the works of thought and tenderness we make with the whole of who we are.