Only by such a misapprehension of freedom, Watts observes, do we ever feel unfree: When we enter a state that causes us psychological pain, our immediate impulse is to get the “I” out of the pain, which is invariably a resistance to the present moment as it is; because we cannot will a different psychological state, we reach for an easy escape: a drink, a drug, a compulsive scroll through an Instagram feed. All the ways in which we try to abate our feelings of abject loneliness and boredom and inadequacy by escaping from the present moment where they unfold are motivated by the fear that those intolerable feelings will subsume us. And yet the instant we become motivated by fear, we become unfree — we are prisoners of fear. We are only free within the bounds of the present moment, with all of its disquieting feelings, because only in that moment can they dissipate into the totality of integrated reality, leaving no divide between us as feelers and the feelings being felt, and therefore no painful contrast between preferred state and actual state. Watts writes:

The sense of not being free comes from trying to do things which are impossible and even meaningless. You are not “free” to draw a square circle, to live without a head, or to stop certain reflex actions. These are not obstacles to freedom; they are the conditions of freedom. I am not free to draw a circle if perchance it should turn out to be a square circle. I am not, thank heaven, free to walk out of doors and leave my head at home. Likewise I am not free to live in any moment but this one, or to separate myself from my feelings.

Without the motive forces of pleasure and pain, it might at first appear paradoxical to make any decisions at all — a contradiction that makes it impossible to choose between options as we navigate even the most basic realities of life: Why choose to take the umbrella into the downpour, why choose to eat this piece of mango and not this piece of cardboard? But Watts observes that the only real contradiction is of our own making as we cede the present to an imagined future. More than half a century before psychologists came to study how your present self is sabotaging your future happiness, Watts offers the personal counterpart to Albert Camus’s astute political observation that “real generosity toward the future lies in giving all to the present,” and writes:

So long as the mind believes in the possibility of escape from what it is at this moment, there can be no freedom.

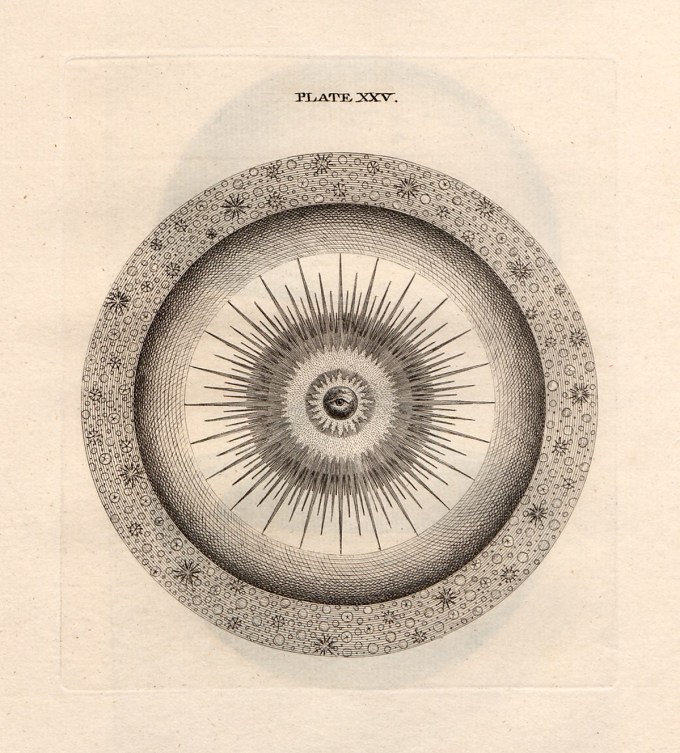

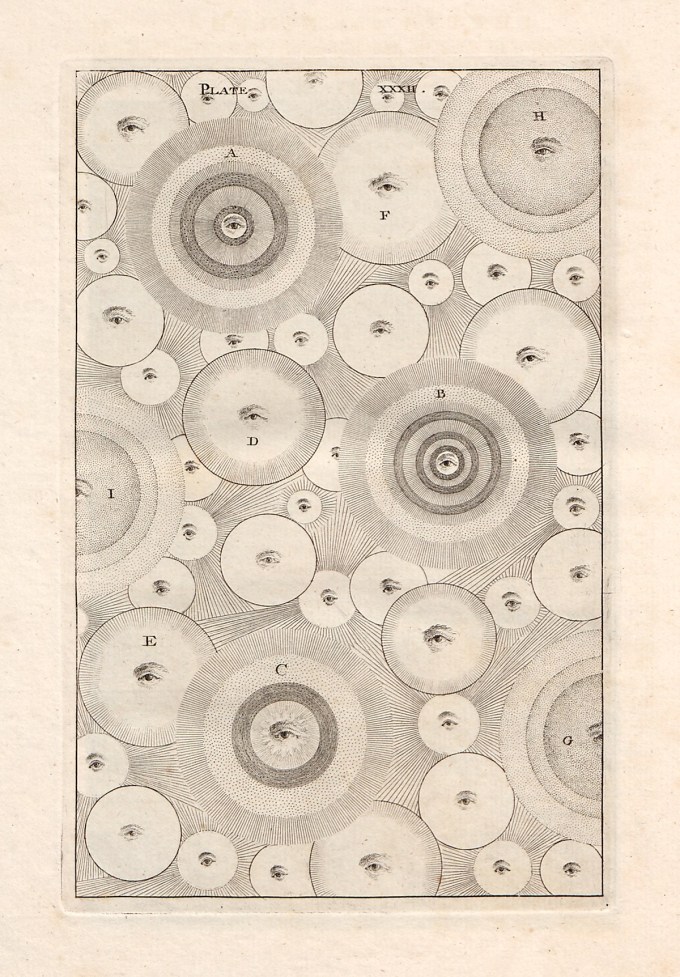

The further truth that the undivided mind is aware of experience as a unity, of the world as itself, and that the whole nature of mind and awareness is to be one with what it knows, suggests a state that would usually be called love… Love is the organizing and unifying principle which makes the world a universe and the disintegrated mass a community. It is the very essence and character of mind, and becomes manifest in action when the mind is whole… This, rather than any mere emotion, is the power and principle of free action.

It sounds as if it were the most abject fatalism to have to admit that I am what I am, and that no escape or division is possible. It seems that if I am afraid, then I am “stuck” with fear. But in fact I am chained to the fear only so long as I am trying to get away from it. On the other hand, when I do not try to get away I discover that there is nothing “stuck” or fixed about the reality of the moment. When I am aware of this feeling without naming it, without calling it “fear,” “bad,” “negative,” etc., it changes instantly into something else, and life moves freely ahead. The feeling no longer perpetuates itself by creating the feeler behind it.

You can only live in one moment at a time, and you cannot think simultaneously about listening to the waves and whether you are enjoying listening to the waves. Contradictions of this kind are the only real types of action without freedom.

The meaning of freedom can never be grasped by the divided mind. If I feel separate from my experience, and from the world, freedom will seem to be the extent to which I can push the world around, and fate the extent to which the world pushes me around. But to the whole mind there is no contrast of “I” and the world. There is just one process acting, and it does everything that happens. It raises my little finger and it creates earthquakes. Or, if you want to put it that way, I raise my little finger and also make earthquakes. No one fates and no one is being fated.

That in love and in life, freedom from fear — like all species of freedom — is only possible within the present moment has long been a core teaching of the most ancient Eastern spiritual and philosophical traditions. It is one of the most elemental truths of existence, and one of those most difficult to put into practice as we move through our daily human lives, so habitually inclined toward the next moment and the mentally constructed universe of expected events — the parallel universe where anxiety dwells, where hope and fear for what might be eclipse what is, and where we cease to be free because we no longer in the direct light of reality.

Events look inevitable in retrospect because when they have happened, nothing can change them. Yet the fact that I can make safe bets could prove equally well that events are not determined but consistent. In other words, the universal process acts freely and spontaneously at every moment, but tends to throw out events in regular, and so predictable, sequences.

[…]

[…]

Half a century before her, Leo Tolstoy — who befriended a Buddhist monk late in life and became deeply influenced by Buddhist philosophy — echoed these ancient truths as he contemplated the paradoxical nature of love: “Future love does not exist. Love is a present activity only.”

This model of freedom is orthogonal to our conditioned view that freedom is a matter of bending external reality to our will by the power of our choices — controlling what remains of nature once the “I” is separated out. Watts draws a subtle, crucial distinction between freedom and choice:

This model of freedom is orthogonal to our conditioned view that freedom is a matter of bending external reality to our will by the power of our choices — controlling what remains of nature once the “I” is separated out. Watts draws a subtle, crucial distinction between freedom and choice:

This model of freedom is orthogonal to our conditioned view that freedom is a matter of bending external reality to our will by the power of our choices — controlling what remains of nature once the “I” is separated out. Watts draws a subtle, crucial distinction between freedom and choice:

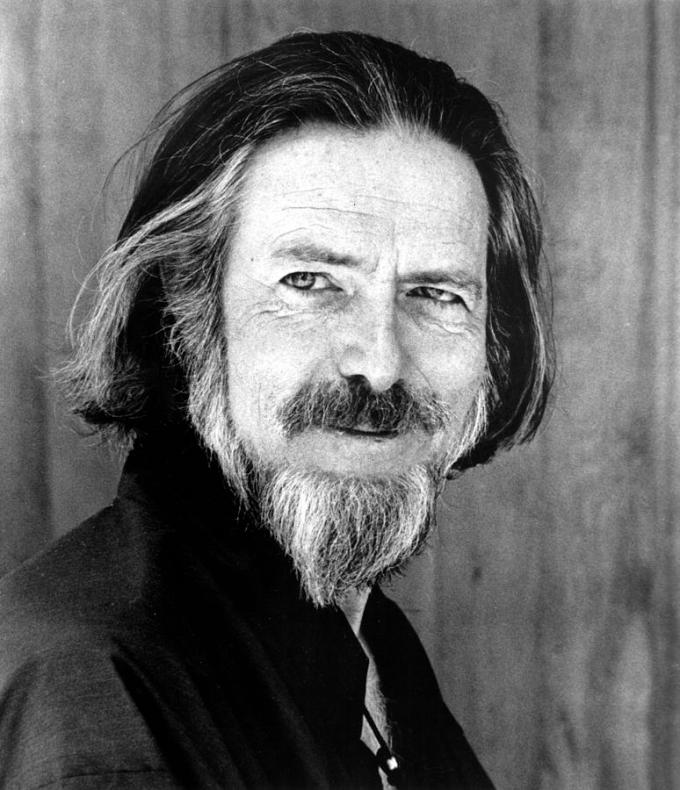

The relationship between freedom, fear, and love is what Alan Watts (January 6, 1915–November 16, 1973) explores in one of the most insightful chapters of The Wisdom of Insecurity: A Message for an Age of Anxiety (public library) — his altogether revelatory 1951 classic, which introduced Eastern philosophy to the West with its lucid and luminous case for how to live with presence.

I fall straight into contradiction when I try to act and decide in order to be happy, when I make “being pleased” my future goal. For the more my actions are directed towards future pleasures, the more I am incapable of enjoying any pleasures at all. For all pleasures are present, and nothing save complete awareness of the present can even begin to guarantee future happiness.

To dissolve into this total reality of the moment is the crucible of freedom, which is in turn the crucible of love. In consonance with Toni Morrison’s insistence that the deepest measure of freedom is loving anything and anyone you choose to love and with that classic, exquisite Adrienne Rich sonnet line — “no one’s fated or doomed to love anyone” — Watts considers the ultimate reward of this undivided mind:

Stripped of the paraphernalia of circumstance and interpretation, our internal experience of being unfree stems from attempting impossible things — things that resist reality and refuse to accept the present moment on its own terms. Watts writes: